In dealing with past human rights abuses and upholding standards of respect for human rights, the Gambia’s transition from an abusive regime to a democracy must also entail justice for victims of gender-based violence. The most illustrative example of addressing sexual violence as a part of the democratization of society occurred last month when 23-year-old former beauty queen, Fatou ‘Toufah’ Jallow accused former President Jammeh of rape.

Toufah detailed her story, which began when she won the state-sponsored beauty pageant in 2014 at 18 years old. Over the following few months, Jammeh lavished her with cash gifts and other favors including the installation of running water in her family house. She was offered a position as a “protocol girl,” to work at the State House, which she declined. She also turned down his marriage proposal.

During a pre-Ramadan Quran recital at State House, Jammeh locked her in a room and told her: “There’s no woman that I want that I cannot have.” She said that he then hit and taunted her, injected her with a liquid, and raped her. Days later, she fled to the neighboring country of Senegal.

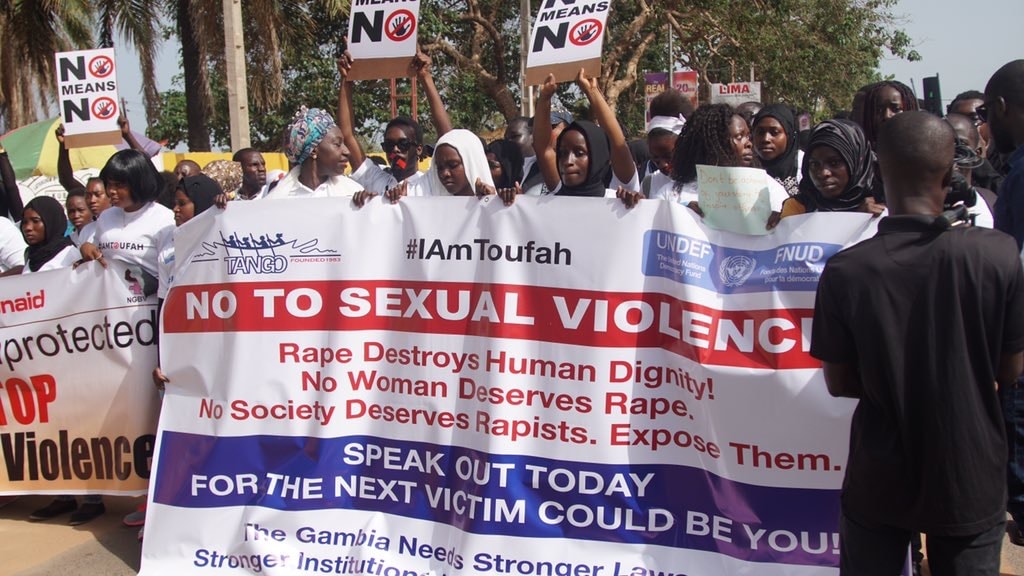

Photo Credit: Human Rights Watch

Additionally, Fatoumatta Sandeng, the spokesperson of the #Jammeh2Justice campaign and daughter of Solo Sandeng, was also confined to a hotel in Jammeh’s home village of Kanilai for several days. She is a well-known band singer and had caught Jammeh’s eye when she performed on TV. She was released unharmed because Jammeh had to attend a funeral.

These public allegations against Jammeh which accuse him of coercing and forcing young women to have sex with him, sparked an investigation into the issue of rape and other sexual crimes during his rule from July 1994 to January 2017 with the intent of prosecuting him. The Gambia Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission, will be a vital platform to establish the history of systemic abuse of young women by Jammeh. It is currently establishing the nature, causes, and extent of violations and abuses of human rights that he committed during his presidency.

The Creation of a Movement

Following the public rape allegations against Jammeh, the Gambia’s #MeToo movement has been triggered. The overdue public reckoning of sexual violence has led to the creation of the social media hashtag #IAmToufah. Women, both in and outside of the country, shared their own experiences of sexual assault. These stories led to other hashtags such as #SurvivingMelville. This widespread response to Toufah’s and Fatoumatta’s stories highly accentuates the demand in the Gambia for accountability and justice. The Women’s Act 2010 defines violence against women as:

All acts perpetrated against women which cause or could cause them physical, mental and emotional, sexual, psychological or economic harm or suffering to women, including the threat to take such acts, or to undertake the imposition of arbitrary restrictions on or deprivation of fundamental freedoms in private or public life, in peace time and during situations of armed conflicts or of wars.

The #IAmToufah movement displays the incredible strength and courage of women and girls to talk about sexual violence. However, the public debate about sexual assault quickly led to denunciation by rape apologists of the “so-called victims” as “liars and people to be blamed [for the rape]”. The urge to brand the victim as a willing collaborator is unfortunate but not bewildering, especially given the Gambian context. The harsh judgement and victim blaming of survivors show society’s complicity in silencing and stigmatizing victims of gender-based violence, including rape.

The Movement’s Oppressors

Ironically enough, some of the fiercest denialists are actually women. This conformity to societal expectations is illustrative of the way systematic domination renders these women incapable of understanding their participation in and reinforcement of their own oppression.

The denialist attitudes held by people in the Gambia reflects the national rhetoric on rape, contested understandings of ‘consent’ and the patriarchal nature of the country’s society. Rape should be understood not just in terms of the harm that individual victims suffer, but as a pillar of patriarchy; it is a central part of many cultures in the Gambia.

Patriarchy is “the systematic, structural, unjustified domination of women by men. It consists of those institutions, behaviours, ideologies, and belief systems that maintain, justify and legitimate male gender privilege and power.” (Braam & Hessini 2004). Rape is not just about sexual desire; it becomes a way of disciplining women when men believe there is a threat to their masculinity or when women do not exercise their traditional roles.

Gender-based violence (GBV), mostly against women and girls, is one of the most pervasive forms of human rights violations perpetrated. It is therefore appropriate that we demand justice. According to the 2013 Gambia Demographic and Health Survey (DHS), 4.6% of people ages 15–59 have experienced sexual violence in the 12 months preceding the report.

On July 4, 2019, hundreds of women and men, boys and girls marched in solidarity demanding that the government and society take concrete action to end gender-based violence in the Gambia. What was out there on the streets was a moving mass of action giving voice to rage. They carried placards with words that seethed.

“No means No.”

“No more rape.”

“We are coming for you.”

This national discourse and reflection on the ongoing problem begs the question:

Why does the culture of rape continue?

The culture of impunity that has perpetuated our society for the past two decades serves as the foundation for the lack of justice for survivors of sexual violence. Although, the Gambia currently has a regulatory framework that addresses GBV including the Children’s Act (2005), Women’s Act (2010), Tourism Offences Act (2003) and Sexual Offences Act (2013), sexual violence remains unabated. While there is no national figure on the prevalence, we do know that sexual abuse is often commonplace for women and girls in the Gambia.

Reporting, much less prosecution, hardly takes place. Victims may be afraid to report violence, especially if the person who has hurt them is powerful or in a position of trust and authority and could harm them again. Furthermore, given the nature of Gambian society, victims are afraid of societal condemnation and stigma, making them even more reluctant to report sexual assault.

The state condones and perpetuates violence when it does not effectively implement laws that protect women and girls from that violence. Effectively, the government allows for impunity. When the state does not hold perpetrators accountable, it sends a message that male violence as a mechanism of control over women is acceptable, thereby leading to normalization of the violence.

The current socio-cultural system serves as a foundation that entrenches and perpetuates these sexual crimes. There is a general social acceptance of violence and preservation of inequality. The Gambia is a deeply patriarchal society, which creates unequal power relationships between men and women and maintains gender stereotypes.

A gender stereotype is defined as “a generalised view or preconception about attributes, or characteristics that are or ought to be possessed by women and men or the roles that are or should be performed by men and women” (Cook and Cusack, 2010, p.9). Rape is part of the patriarchal system in the Gambia that promotes low status of women. Whilst women constitute more than half of the Gambian population, society does not equally value women and girls. As noted elsewhere, “[a]t the heart of gender inequality lies unequal power relations between women and men in our societies, where men control and dominate over women’s lives.”

Editor’s Picks — Related Articles:

Is Gender Equality a Numbers Game?

Uabalika, A Movement to Empower All Women: Interview with Andra Massamba

What will it take to address the issue?

While we have laws and policies, it is vital that we ensure effective enforcement mechanisms are also in place. This would include the strengthening of the justice system and the police to deal with cases expediently as victims need to be provided with just and effective remedies. Perpetrators of all forms of sexual violence should be prosecuted and punished.

In addition to the provisions in the above mentioned laws, the new Gambian constitution must include the prohibition of violence against women and girls in both the private and public spheres. Constitutions serve as important frameworks for articulating a State’s condemnation of violence against women in line with international standards. The inclusion of such a constitutional protection will be premised on the basis that gender-based violence violates the fundamental rights of women and limits their opportunities and choices. The state is also obligated to prevent the violation of women’s rights by state (i.e. the police or military) and non-state actors (i.e. spouse, partner or employer) for the establishment of equality in all spheres.

Equally important, civil society organisations need to collectivize efforts and continue to challenge attitudes and stereotypes that engender gender-based violence and perpetuate the subordination of women and unequal distribution of power between women and men. Assertions of culture and religion cannot be continually used to justify violations of women’s rights.

What the #IAmToufah movement brings to the table is not just a portrayal of women and girls as victims of violence but spotlighting the abusers who must be named, shamed and brought to face justice. #TimeIsUp as the Gambia makes the choice to not tolerate, condone or excuse sexual violence committed against women and girls. It is time we stop finding excuses for rapists. Rape is never acceptable, and perpetrators will not go unpunished.