This article is the fourth of the series: Pipe dream or achievable vision: How can we deliver on the 2030 Agenda?

The 2030 Agenda foresees a bright future for humanity, one in which everyone enjoys peace and prosperity on a bountiful planet. But, with nationalism, populism and protectionism on the rise, how can we deliver on this utopian vision? This series of articles looks at what the international development system needs to do to deliver on this incredibly complex task – from rebuilding trust in multilateralism to bringing in the trillions of dollars needed each year to finance change.

The first article can be found here: “Trust or bust: The UN must put its house in order to attract finance for development”. The second article – “How 2030 Agenda Provides Chance for Countries to Escape “Middle-Income” Trap and Help Finance Global Development”. The third article – “Global Food Systems and Aid for Trade: a Good Mix for Financing the SDGs”.

Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (BRICS), five of the world’s most important emerging economies, are increasingly flexing their muscles on the world stage as power dynamics shift, making them key players in the prospects of success for the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

The bloc is presenting a strategy for creating a world order that includes a bigger role for developing nations and is becoming a meeting place for developing countries and the platform for South-South cooperation.

The BRICS are members of the G20, accounting for 43 percent of the world’s population, at least 23 percent of global GDP, and at least 16 percent of world trade. In their first decade of partnership, the BRICS countries have become a cohesive force with a strong desire to advance their development strategies by coordinating macroeconomic policy.

Their influence is seen in many areas. In 2016, Russia became the largest wheat exporter in the world. China has the globe’s largest industrial and manufacturing capacity. India is to the fore of the scientific, technological and pharmaceutical fields. Brazil is endowed with abundant mineral, water, biological and ecological resources, and South Africa abounds in natural resources.

IN THE PHOTO: A worker at the Kwangchow Centre checks the growth of carp fingerlings prior to transferring them to maturing ponds. – – Fish Farming Techniques. The domestic raising of fish in village ponds has been practised in China for more than 2,000 years. CREDIT: FAO/Florita Botts

The past decade has seen growing cooperation among the BRICS in trade, infrastructure finance, urbanization and climate change. There has been progress in people-to-people connections and an improved understanding of each other’s industry, academia and government through platforms such as the BRICS Academic Forum and Business Council.

Additionally, a new international mechanism for financial opening and macro-control is forming, focusing on spreading the application of projects such as Shanghai’s new smart energy demonstration project, Brazil’s renewable energy transfer project, India’s renewable energy power supply and loan project, South Africa’s transmission network and other new energy projects.

With the implementation of the 2010 International Monetary Fund (IMF) reform, an important step has been taken in further boosting the influence of the BRICS. They need to continue pushing forward the reform of the Bretton Woods institutions to increase the voice and representation of emerging markets and developing countries in global economic governance.

The above developments mean that the BRICS are well positioned to take a leading role in helping to achieve the 2030 Agenda. The trick is to ensure that they work with the traditional “Western” powers rather than each viewing the other with a competitor’s eye.

BRICS impact on aid architecture and development finance

Two components make up the financial architecture of BRICS: the New Development Bank (NDB) and the Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CRA). Their institutionalisation has been the BRICS’ most-notable achievement, marking a shift from rhetoric to results and offering credible alternatives to the Atlantic system of global governance.

IN THE PHOTO: 22 October 2014, Rome – Communicating to Inspire Change: BRICS Dialogue on Nutrition, FAO headquarters (Sheikh Zayed Centre). CREDIT: FAO/Alessia Pierdomenico

BRICS+ – through which Indonesia, Turkey and Mexico could become members – speaks for the majority of developing countries and seeks development assistance for them. It has set up emergency foreign exchange reserves, established the NDB, and expanded into other types of cooperation. After the issuance of renminbi bonds for the first time in China, these will also be made available in India, Brazil, and Russia. The NDB could be an opportunity to involve experts and equipment from the BRICS countries, in contrast to projects financed by the IMF or the World Bank, which usually deploy resources from western countries.

Development financing from the BRICS perspective tends to differ from that of Russia and traditional donors, which emphasise the role of aid in poverty reduction. The other BRICS countries, on the contrary, provide financial assistance based on mutual benefits, in line with the principles of South-South cooperation.

BRICS, in particular, China, avoid policy conditionality on the grounds that it interferes with the recipients’ sovereignty, and tend to provide non-cash financing in order to circumvent corruption. Traditional donors, on the other hand, view policy conditionality as a means to ensure the efficient use of aid.

There are also different views on obtaining debt sustainability. Some BRICS countries lean towards micro-sustainability and growth, while traditional donors pay more attention to macro-sustainability in the long term. The gap, however, is narrowing, as the BRICS increasingly realize the importance of overall debt sustainability and traditional donors see the need for investing in physical capital and obtaining results.

IN THE PHOTO: Farm family working in a field of rice that has been cultivated using new technologies. – – Special Programme for Food Security. The Special Programme for Food Security (SPFS) is being implemented in ten counties of China. CREDIT: FAO/Antonello Proto

The role of India

A gradual revolution is underway in global development. Development assistance offered by western states is usually based on a hierarchical relationship between donor and recipient. Emerging economies like India are evolving new financial instruments and institutional arrangements to facilitate development cooperation.

India avoids terms such as ‘donor’ and ‘aid’, and frames its programmes in the context of a mutually beneficial partnership that is demand-driven and politically non-conditional. India has transformed from a poor recipient country to a development partner with global interests and ambitions. It now provides relief assistance to bilateral partners, has cancelled the debts of some heavily indebted countries, and launched the India Development Initiative to provide grants, loans and project assistance to developing countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America.

Since the early 2000s, reflecting its growing economic interests, India has also begun to use Lines of Credit (LOC) or export credits as one its key development partnership instruments. These, together with trade and investment, technology, skills upgrade and grants, significantly raise the total amount India pledges towards development partnerships.

The recent liberalisation of labour and environmental regulations at central and state government levels, coupled with generous new financial incentives for investment, should result in deep structural changes that boost growth in India. Policies are being redesigned to attract additional foreign investment into the manufacturing, hydrocarbons, insurance, defence and railways sectors.

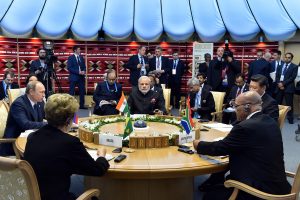

IN THE PHOTO: Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (BRICS) leaders meet on the margins of the G20 Summit in Antalya, Turkey (2015). President of Brazil Dilma Rousseff, Prime Minister of India Narendra Modi, President of Russia Vladimir Putin, President of China Xi Jinping and South Africa’s President Jacob Zuma. CREDIT: GCIS via Flickr

At the BRICS meeting in Xiamen, China, in September 2017, Prime Minister Narendra Modi commented that the group contributed “stability and growth in a world drifting towards uncertainty”, and asked BRICS to team up with the International Solar Alliance (ISA), which brings together a coalition of 121 countries for mutual gains through enhanced solar energy utilisation.

He called for the speeding up of the creation of a BRICS credit rating agency, for which an expert group has already been constituted, and exhorted Central Banks to further strengthen their capabilities and promote cooperation between the Contingent Reserve Arrangement and the IMF. Modi said a strong partnership among member-nations on innovation and the digital economy could help spur growth, promote transparency, and support the sustainable development goals.

He also underlined the need for scaling up cooperation in skill development and exchange of best practices, with a particular focus on Africa, adding that “India would be happy to work towards more focused capacity-building engagement between BRICS and African countries in areas of skills, health, infrastructure, manufacturing and connectivity”.

India, Modi said, was in “mission-mode” to eradicate poverty and ensure health, sanitation, skills, food security, gender equality, energy and education. He indicated that women empowerment programmes were “productivity multipliers” that brought women into the mainstream of nation-building.

BRICS and the LICs

Such actions are a clear sign that the BRICS can help lift up less-prosperous nations. Economic relations between low-income countries (LICs) and BRICS have strengthened over the past decade and both sets of countries have found it beneficial to boost their economic cooperation.

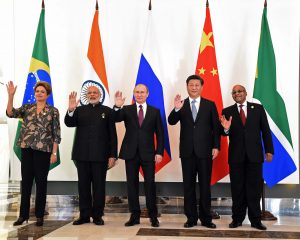

IN THE PHOTO: President of Russia Vladimir Putin with President of Brazil Dilma Rousseff, President Jacob Zuma, Prime Minister of India Narendra Modi and President of China Xi Jinping during the BRICS Leaders Meeting. CREDIT: GCIS via Flickr

Rapid economic expansion in BRICS and the strong economic complementarity between the two groups of countries have underpinned the rapid growth and high intensity of bilateral trade – many LICs have a strong comparative advantage in commodities, while most BRICS countries are competitive producers of manufactured goods.

Despite its small overall volume compared with OECD financing, development financing from BRICS has enabled many LICs to increase power generation and transport networks, alleviate infrastructure bottlenecks and reduce poverty.

Given the relatively low saving rates and lack of technology and skills in most LICs, more Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) is needed to help strengthen domestic productive capacity and improve competitiveness. Continued efforts should be made to improve the business environment, upgrade labour skills, foster technology transfer, and integrate FDI firms into local economies.

Embracing policy reforms to meet these challenges will place LICs in a stronger position to reap the long-term benefits of global integration.

Addressing poverty through rural development

Poverty today is primarily rural, so accelerating rural development – with a big focus on agriculture – will be key to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. In low-income countries, growth originating from agriculture is twice as effective in reducing poverty as growth originating from other sectors. It is important that the tools, approaches and technologies developed are useful and accessible to poor family farmers in developing countries so that they can increase production and productivity.

Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) also help to address many of the challenges smallholders face accessing information on prices, weather forecasts, vaccines, financial services, and so on. FAO is collaborating with the G20, the OECD and the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) to make sure these technologies benefit smallholders.

Agricultural growth requires investments in R&D, and the BRICS could play a leading role in this, as all five countries have strong agricultural research systems that are working on many of the challenges faced by developing countries, such as feeding a growing population in a sustainable way. Biotechnology could also play a key role in these advances, as could agroecological approaches. Climate-smart agriculture will be essential to adapt to the uncertain changes that farmers face. This will rely heavily on cutting-edge research.

Of course, agricultural growth on its own cannot eradicate hunger and poverty. It needs to be accompanied by social protection programmes, which have poverty reduction and health benefits and can also strengthen the confidence of family farmers, encouraging them to become more entrepreneurial. Brazil’s Fome Zero and India’s National Rural Employment Guarantee Act are global references in this regard.

It is now necessary to consolidate the gains for the BRICS and move forward towards an inclusive and global Agenda 2030. To do so it is important that BRICS and the West see each other as partners and not competitors.

FEATURED IMAGE CREDIT: FAO/Jon Spaull

Editors note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com