According to the World Health Organization (WHO), electronic waste (e-waste) is one of the fastest-growing waste streams today. While most e-waste contains resources that are valuable and finite in nature, less than a quarter is recycled. In 2022, 62 million tonnes of e-waste were produced around the world but only 22.3% were recycled.

E-waste is a term used to describe anything that is discarded and that has a plug (requires charging) or a battery.

The world’s level of e-waste increased by 82% from 2010 to 2022, and the United Nations’ e-waste monitor projects that it will rise another 32% by 2030.

The problem is that, while the amount of e-waste being produced continues to grow, the growth of recycling capacity cannot keep up. As a result, “the recycling rate could actually drop over the next few years,” according to Vanessa Gray, an e-waste expert with the International Telecommunication Union.

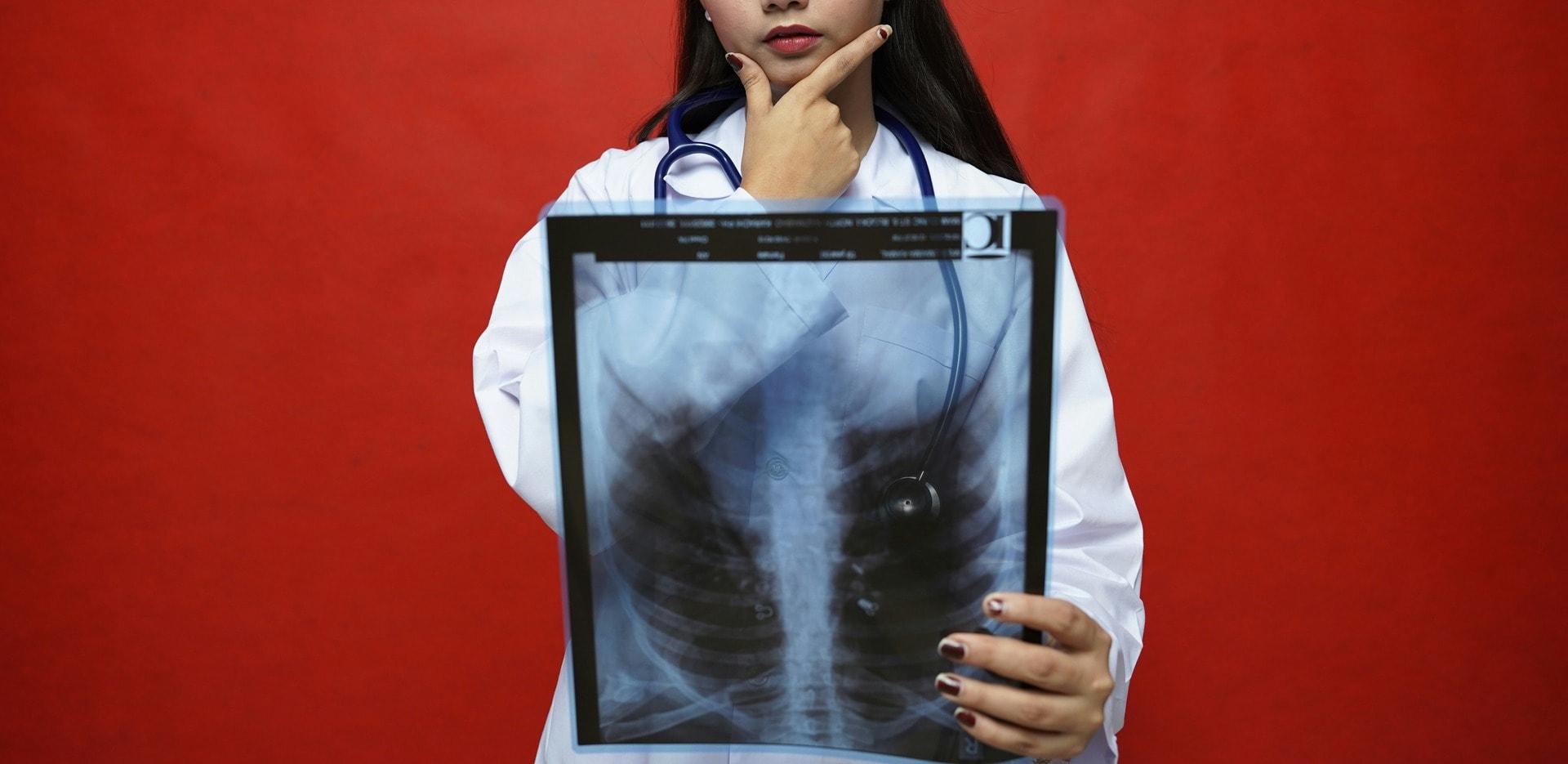

Toxic e-waste is a public health concern

E-waste is considered toxic waste. It can contain hazardous materials that produce chemicals and neurotoxins that harm human health — including lead, mercury and various dioxins. The growing levels of e-waste, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, have become a public health concern.

Various malpractices in the disposal of electronic waste cause both public health and environmental problems. Exposure to the toxic chemicals released by e-waste through scavenging has been known to be harmful to humans, particularly children.

The International Labour Organization (ILO) estimated in 2020 that up to 16.5 million children work in the industrial sector, with waste processing being a subsector. While it is not known how many child labourers work directly in e-waste recycling, the ILO considers it to be one of the worst forms of child labour. E-waste exposure can hurt neurodevelopment and lung function among children, and can cause negative neonatal outcomes, including stillbirths in pregnant women.

Most users of day-to-day electronics will not in fact come into contact with many of the harmful substances created by e-waste. It is only when they become waste that these toxins are usually released. This is in large part due to how this waste is disposed of. Dumping e-waste into water or landfills with regular waste, burning or heating the waste, putting it in acid baths or leaches, or stripping plastic coatings all increase the hazardous nature of e-waste and its ability to harm humans.

It is also an environmental concern

Most, if not all, electronic devices require raw materials that are extracted from the earth using energy-intensive processes, usually powered by fossil fuels. Many electronic devices have lifespans of only a few years, meaning that demand for electronics is continuous and that the impact of electronics production on the climate is still growing.

If these products were disposed of correctly and e-waste was properly managed, pollution would decrease, according to the UN’s e-waste monitor.

“The more metals we recycle, the fewer have to be mined,” says Kees Baldé, a senior scientific specialist at the UN Institute for Training and Research.

An estimated 52 million metric tonnes of emissions were avoided in 2022 due to recycling metals from e-waste instead of extracting new ones.

Related Articles: Fast Tech ‘Seriously Rivalling Fast Fashion’: How Bad Is the Electronic Waste Crisis? | Electronic Waste Recycling Could Save Key Metals | Talking Trash | Should We Be Worried About Nuclear Waste? | ‘Dead White Mans’ Clothing’ Polluting the Global South

What can be done to address the e-waste crisis?

The WHO has a framework with the goal of fixing the e-waste crisis. This framework currently includes eliminating child labour, as it relates to e-waste but elsewhere as well. The organization aims make the detrimental health effects of e-waste on children its biggest focus.

The WHO’s Initiative on E-waste and Child Health has already led to the development of programmes and projects implemented in Latin America and Africa — two of the more at-risk regions. The WHO also releases reports and training tools for the health sector, globally, to train healthcare providers on the risks of e-waste exposure, particularly amongst children.

Additionally, the WHO pushes for more high-level international agreements to address the problem, more national and international legislation through the lens of public health and monitoring and dealing with e-waste sites directly.

The Basel Convention, for example, was created to control the movement and disposal of hazardous wastes. One piece of legislation coming from the Basel Convention is the Ban Amendment from 2019, which prohibits the movement of hazardous waste, including e-waste, between countries of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the European Commission and any other countries signed to the Convention.

Other regional conventions were created in response to the Basel Convention, including the Bamako Convention and the Waigani Convention, which address hazardous waste and their negative health and environmental effects in Africa and the South Pacific, respectively.

Who is to blame?

Without question, there are many culprits in the growing e-waste crisis. Irresponsible consumers, waste management companies who participate in various malpractices, governments and organizations that do not adequately address the issue; all of them play a role. But manufacturers have been proven to dismiss the problem caused by their electronics, failing to build long-lasting products and failing to consider what happens when their product is disposed of.

Jim Puckett, founder and executive director of the Basel Action Network, said that the data on e-waste shows “a lack of duty of care” among manufacturers.

He adds that “manufacturers have to be dragged, kicking and screaming,” to address the issue by making products that are more sustainable, for example. “Not just [to] design products for the dump, hoping they can sell us a new one as soon as possible.”

Still, even with concern growing, manufacturers often remain unchecked, and only 81 countries had e-waste policies in 2023. The United States, among the largest producers of e-waste, does not have any federal laws requiring that electronics be recycled.

Even with policies in place in certain countries, enforcing this legislation “remains a genuine challenge globally,” according to the authors of the UN’s e-waste report in 2024.

Baldé claims that one of the quickest ways to address the problem is to stop wealthy countries from dumping their e-waste in developing countries, who do not have the capacity to deal with it.

“Simply put — business as usual can’t continue,” he adds.

At current rates, this problem will only continue to grow. With the resulting public health and environmental fallout, manufacturers, consumers and governments alike will no longer be able to ignore e-waste and its piling side-effects.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Cover Photo: A young boy carrying electronic waste, Accra, Ghana, September 2011. Cover Photo Credit: The Basel, Rotterdam and Stockholm Conventions.