These are times when we want to believe in some institution – any institution, but especially the Nobel Prize. According to Alfred Nobel’s will of 1895, the Nobel awards are to “those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind.” But despite vast changes that have taken place in the world over 120 years since the Nobel award began, the “science” categories do not include “technology.” And with respect to the Peace award, in some cases, the Nobel winners appear to be based more on future hope than impact, and perhaps are unintentionally biased.

A look at the Nobel Prize history, including the Nobel Foundation and processes to cover awards categories, throws light on the issue.

The Nobel Foundation, Academy, and The Award Selection Process

The simplest way to capture the gist of Alfred Nobel’s will is by drawing on Section One of the” Objects of the Foundation”, which reads in part:

“The whole of my remaining realisable estate shall be dealt with in the following way: the capital, invested in safe securities by my executors, shall constitute a fund, the interest on which shall be annually distributed in the form of prizes to those who, during the preceding year, shall have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The said interest shall be divided into five equal parts, which shall be apportioned as follows: one part to the person who shall have made the most important discovery or invention within the field physics; one part to the person who shall have made the most important chemical discovery or improvement; one part to the person who shall have made the most important discovery within the domain of physiology or medicine; one part to the person who shall have produced in the field of literature the most outstanding work in an ideal direction; and one part to the person who shall have done the most or the best work for fraternity between nations, for the abolition or reduction of standing armies and for the holding and promotion of peace congresses.

The prize for physics and chemistry shall be awarded by the Swedish Academy of Sciences; that for physiological or medical works by Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm; that for literature by the Academy in Stockholm; and that for champions of peace by a committee of five persons to be elected by the Norwegian Storting (national parliament).

It is my express wish that in awarding the prizes no consideration whatever shall be given to the nationality of the candidates, but that the most worthy shall receive the prize, whether he be a Scandinavian or not.” (Emphasis added)

A fifth category for economics — the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel – was created in 1968 by Sweden’s central bank, the recipients of which are selected by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

The Nobel Academy has about 450 Swedish and 175 foreign members with separate institutions identified for each category. Nobel Committees of three to five members are appointed to evaluate nominations for the respective Nobel Prizes; they extensively examine a selection of the nominees submitted by some 3,000 participants. These “Committees” present proposed candidates to the specific prize-awarding institution. The actual decision is made not by these Nobel Committees, but by consensus of all members of the prize-awarding institution.

Albert Einstein was denied the Physics award in 1921 for his Theory of General Relativity in part because at least one Committee member, a German physicist, Philipp Lenard who was a fervent anti-Semite, opposed his selection. Einstein ultimately won a Nobel in 1922 for his work on the photoelectric effect.

The Peace Prize is treated separately by the Norwegian National Parliament. The Parliament appoints five members to a Norwegian Nobel Committee, which is responsible both for evaluating the nominees and selecting the recipient.

Announcements of recipients are made each year in October with the awards presented on December 10th, in Stockholm for five categories, and in Oslo for the Peace Prize. From 1901 when the award process began, until 2020, there have been 962 Nobel Laureates awarded, 143 shared by two winners and 108 shared by three recipients. This year, there are 329 candidates for the Nobel Peace Prize out of which 234 are individuals and 95 are organizations.

Announcements of recipients are made each year in October with the awards presented on December 10th, in Stockholm for five categories, and in Oslo for the Peace Prize. From 1901 when the award process began, until 2020, there have been 962 Nobel Laureates awarded, 143 shared by two winners and 108 shared by three recipients. This year, there are 329 candidates for the Nobel Peace Prize out of which 234 are individuals and 95 are organizations.

The youngest Nobel Prize laureate ever, Malala Yousafzai, was only 17 years old when she received the 2014 peace prize. After being shot three times for speaking up for girls’ right to education, Malala keeps fighting for education for all.

Learn more: https://t.co/7t9zr3VOMO pic.twitter.com/HOG9HVLPJD

— The Nobel Prize (@NobelPrize) September 9, 2021

The Nobel Foundation keeps saying its main mission is to ensure that the prize-awarding institutions are guaranteed independence in the selection of winners. But the question is: What does it take to guarantee that independence?

What Needs to Change

The first aspect to consider is whether the existing categories accurately and fairly take into account major twenty-first-century challenges which affect humanity.

Nobel was a Swedish chemist and engineer who envisioned science as a tool primarily to enhance existence. Given his background as the inventor and patent holder for dynamite, Nobel surely would have understood that all technological innovations have the possibility of being forces for both good and evil, and that huge fortunes would be made based on the advent of some technological innovations.

We can easily imagine that if Alfred Nobel were with us today, he would have included a separate “Technology” category to capture the immense impact on humanity of the worldwide web, social media, electric vehicles, alternate power, and even global consumer organizations.

As for the Nobel Peace prize: the Norwegian Parliament is a model of democratic success, both in how members of Parliament are elected and its functions. But sometimes political views and certain notions of political correctness counteract common sense. Barack Obama, for instance, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize very early, much to his and his own wife’s amazement — almost eight months into his Presidency, at which time he hadn’t had a chance to do much of anything. The Nobel Committee figured that his “vision…for a world without nuclear weapons,” and his creation of “a new climate in international politics” as it phrased it, was meritorious enough.

Obama is one example of a Nobel Peace award which “jumped the gun” in not letting time for the dust to settle and a fair evaluation of the historical value to society. There are others, such as Aung San Suu Kyi of Myanmar in 1991 and Abiy of Ethiopia in 2019.

Angela Merkel on the other hand did not get the Peace Prize during the fifteen years she served as German Chancellor – despite her leadership of Europe during tumultuous times.

Her most likely candidacy was in 2015 when she chose to save tens of thousands of desperate Syrian refugees, dealt with Putin’s attack on Ukraine, and managed to preserve the Euro during the Greek economic crisis. The day before the October announcement in 2015 virtually all Nobel observers had her the odds-on favorite.

Why the snub? Ironically, it was likely because Merkel’s immigration decision angered many., enraged many by pointing out spendthrift Greece’s heedless profligacy, Moreover, her handling–some said much too firm- of the Greek financial crisis drew many criticisms and she made no friends in America when she felt it was wa when necessary, frequently to refused to accept misguided American leadership.

What Can Be Done to Improve Fairness, Innovation and Common Sense in awarding Nobel Prizes

First, a new “Technology” category should be created and funded in order to reward modern and life-enhancing innovations. There are technological billionaires, any one of whom could decide to provide a sizeable endowment equivalent to the amount provided by the Swedish Central Bank for the creation of such a prize. The Nobel Foundation, of course, would have to approve all aspects, including vetting potential funders in order to assure total independence from those who contribute and develop the criteria in conformance with the principles espoused in Alfred Nobel’s will.

Second, the selection criteria of the Nobel Prize for Peace should be reviewed, including allowing sufficient time to evaluate historical significance, so that the choice holds true to the Nobel founder’s notion that “no consideration whatever shall be given to the nationality of the candidates” and that the person or persons “have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind”

Neither intra-European politics, ethnicity, nor the “promise” of doing good in the future, should determine the awardee for the Peace Prize or any other Nobel, for that matter.

If these points will be taken as Nobel gospel, the 2021 Peace Prize would go to Angela Merkel. And the technology prize? I leave the choice to tech-savvy readers.

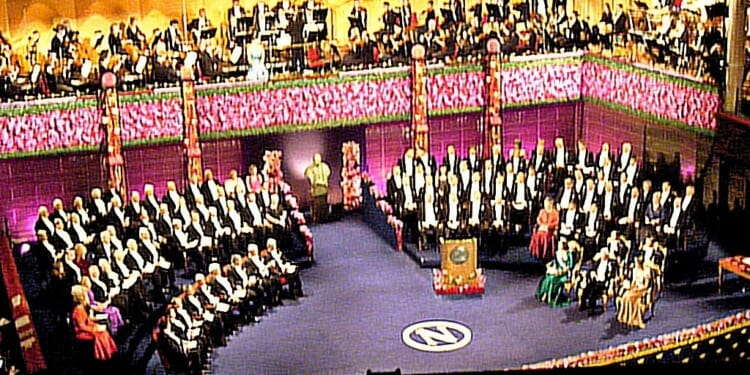

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: Award Ceremony of the Nobel Prize 2010 at the Stockholm Concert Hall (cc)