In Milan, clean air, social inclusion and public health are just some of the reasons we moved to create more space for people to walk and to cycle early in the pandemic. With our Strade Aperte (Open Streets) Plan, we set the goal of reallocating 35 km of road space previously used by cars to routes for people to safely walk and cycle.

Even before COVID-19, we knew that walking and cycling are more efficient ways to move people and goods in congested urban areas. They increase everyone’s access to essential services, boost public health and safety, and slash pollution driving both local disease and the global climate emergency.

Related Articles: Korean “Bike to Work Challenge” Is Leveraging Technology to Tackle Climate Change | Cities key steps to fight against climate change

Italy is known for its fast and sleekly designed automobiles—and the modern, all-electric version has its place in the country’s future. But a densely populated city centre is a place for people, not cars.

Like many other leading cities across Europe and the world, Milan is now helping drive a new renaissance in people-centred, urban development: the 15-minute city. More convenient, less stressful, more sustainable. It revolves around simple forms of active mobility, ensuring everyone is just a short walk or cycle ride from life’s essential goods and services.

The complex requirements and multiple benefits of the 15-minute city—from high-quality careers to improved health for people and planet—make it an ideal focus for green and just economic recovery packages.

I’m proud of Milan’s innovation and leadership and I’m inspired by similar efforts bringing this vision to life elsewhere in the world. More than 2,000 km of new cycle lanes have been announced and/or added globally during the pandemic: the distance between London and Rome.

In response to the COVID-19 crisis, Mexico City began the construction of 54 km of new, designated cycle lanes using recycled materials (from old bus lines). The first one runs along Insurgentes, a city landmark and one of the largest streets in the world. The city’s new vision for cycling is to double bike lane capacity in order to have a total of 600 km of cycling paths in place by 2024.

The new paths will not only cover the city centre but will connect areas across the entire city, supporting active mobility out to the wider periphery. Just as in Milan, expanded infrastructure for walking and cycling forms the core of an integrated effort to ensure well-being for all in the near-term context of economic recovery while paving the way for a transformation towards healthy, equitable, and sustainable cities over time.

Also in Latin America, Colombia’s capital Bogotá—one of the first cities in the world to launch emergency bike lanes—has seen major progress in making active mobility a central pillar of its COVID-19 response. Bogotá added 117 km of temporary cycle lanes to its existing, permanent network of 550 km of cycle routes soon after the lockdown began in March.

As in the U.K. and U.S., the pandemic saw demand for bikes outstrip supply in Bogotá. So a voluntary initiative of civil society and the private sector (Colombia Cares for Colombia) has responded with an integrated effort to develop the broader value chain and policy ‘ecosystem’ required to ensure the city can put cycling and other active transport modes at the centre of recovery efforts.

Last month, 19 bike councils were formed, with citizen representatives charged with advising local and district administrations on policies for cycling and other alternative transportation modes.

In Mumbai (India), cycle advocates have recently emulated Bogotá’s approach, appointing a “bicycle councillor” to help promote cycling infrastructure in each of the city’s 24 wards. Around the world, many other cities have published hugely inspiring and ambitious plans for better, more equitable road space reallocation: Streetspace for London; Safe, Active Transportation Circuits in Montreal, The Great Walk of Athens and Paris’ RER V Plan, to name but a few.

These are just a few examples of hundreds of initiatives that have sprouted around the world to put walking, cycling, and other urban transport innovations at the heart of recovery efforts. They demonstrate the global shift towards supporting more high-quality walking and cycling infrastructure and highlighting active mobility’s role in ensuring cities are welcoming and attractive to people from all walks of life.

Clean air is just one of the many benefits of active mobility. But we don’t need a perpetual worldwide lockdown to create clean air for our residents. Our responses to the COVID-19 crisis are already showing how the new normal can be more resilient, inclusive and sustainable. Now’s the time for blue-sky thinking.

About the author: Giuseppe Sala is the Mayor of the City of Milan, Italy. He has been in the position since June 2016. Previously he has held various managerial positions in both the public and private sector, including as City Manager of the Municipality of Milan. His last role before elected Major was as Managing Director of the Universal Exposition 2015, hosted in Milan.

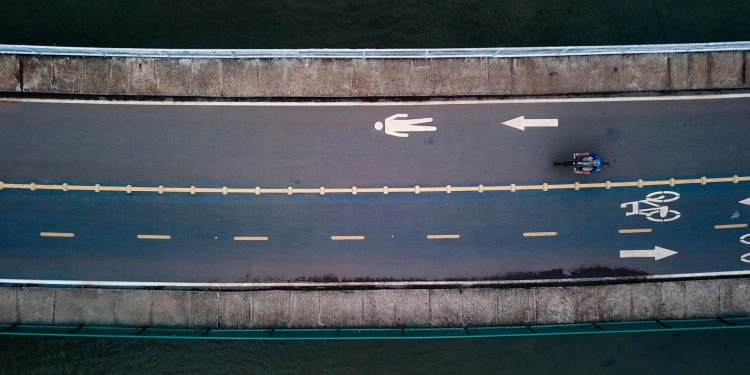

EDITOR’S NOTE: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com.— In the Featured Photo: Aerial shot of city’s park cycle lane, Brazil. Featured Photo Credit: Kande Bonfim / Unsplash