Not much is known regarding the lasting impact of COVID-19 on the education and training of healthcare professionals operating in both human and veterinary medicine. What is certain as of now, is that it is a threat to the kind of education and training needed to ensure the availability of adequately trained health professionals. And the institutions responsible for doing so around the world are pressured more than ever before to produce the rising number of professionals required to meet the pandemic that is now well into its second wave.

Anyone who doubts that we are in the middle of the second wave should take note that both Europe and America are now clocking in at 100,000 new cases each day. Health systems in some countries, notably Belgium, are reaching their “breaking point” as the numbers continue to rise:

Developing and maintaining successful medical and veterinary degree programs is a complex challenge even in non-pandemic times. It is dependent on complex interlinked elements, including adequate infrastructure, faculty, student quality, clinical rotation sites necessary for hands-on training, and financial flows. The latter is a persistent problem everywhere. Funding is rarely sufficient and as a result, a mix of tuition, research grants, and teaching hospitals and/or consulting services, private donations, and public budget support is required to ensure that healthcare education can function as intended.

With the possible exception of research grants to select institutions and healthcare services, prospects for the other major resource in many cases, namely public money, are sharply diminished as politicians rush to respond to the economic demands caused by the pandemic.

In many countries, public universities do not have more capacity or the resources to be able to offer new seats for these two degrees. Private universities rely mostly on tuition and private facility services and consultancies. With high tuition fees, current financial distress in many places makes it difficult for families to support study at high-cost programs.

Problems don’t stop there. For these two similar health professions – physicians and veterinarians – the need for advanced learning spaces and laboratories, clinical and other facilities add costs that are far higher than for many other fields of study.

To illustrate with the example of America. Among graduates with medical school loans in 2019, the average debt is $251,600, according to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) and the median, including loans from premedical education, was approximately $225,000. The situation is not much better for veterinary school graduates who had to take out a loan: “the average” debt was $168,000 and over 20% has at least $200,000 in debt (2016 data). Compare that to the median debt in all fields: $48,000 (including undergraduate and graduate loans – NCES 2018 data).

Before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, there already was a global shortage of both professional disciplines. Regarding the medical profession, the WHO has regularly sounded the alarm and in 2019 the World Medical Association urged governments at the UN to take action, stating that closing the health workforce gap is “essential to achieving universal health coverage”. As WMA Chair Dr. Frank Montgomery noted:

“Today, there are 76 countries with less than one physician per thousand people and three billion people without access to a health professional. It is unacceptable that the patient with cancer in Sierra Leone cannot get the care they need because there is no oncologist in the country or that the woman with obstetric fistula has to suffer because there is no gynecologist”.

For human medical doctors, the world gap is estimated at more than 7 million skilled professionals, with that number likely to grow to nearly 13 million by 2035. For veterinarians, equivalent estimates are hard to come by. But in light of the rising environmental and societal challenges of the 21st century — changes in food animal production, soaring human populations, global warming, invasions of exotic species, and as we know only too well, outbreaks of infectious disease — a rising demand for veterinarian services appears inevitable. It is clear that the field of veterinary science is set to expand as new goals for protecting animal (and human) health have to be met.

How Can the Healthcare Education and Training Systems Meet Pandemic Needs?

In terms of institutional availability, the U.S. and Canada are well-placed, with a large number of medical schools. For example, in 2020, there are 155 human medical schools in the U.S. and 37 osteopathic medical schools. These medical schools graduated almost 20,000 doctors and close to 6,500 osteopathic doctors in 2019.

As to veterinary science, 32 schools or colleges of veterinary medicine in the U.S. and Canada are accredited or have accreditation pending and all of them are American Association of Veterinary Medical Colleges members. These include five Canadian colleges of veterinary medicine, five U.S. departments of veterinary science, six U.S. departments of comparative medicine, 15 accredited international veterinary schools, and 15 non-accredited international veterinary schools

As a comparison of the relative size of the two professions, the U.S. veterinary medical workforce was roughly one-tenth of the size of the human medical profession. So there is ample room (and need!) for expansion.

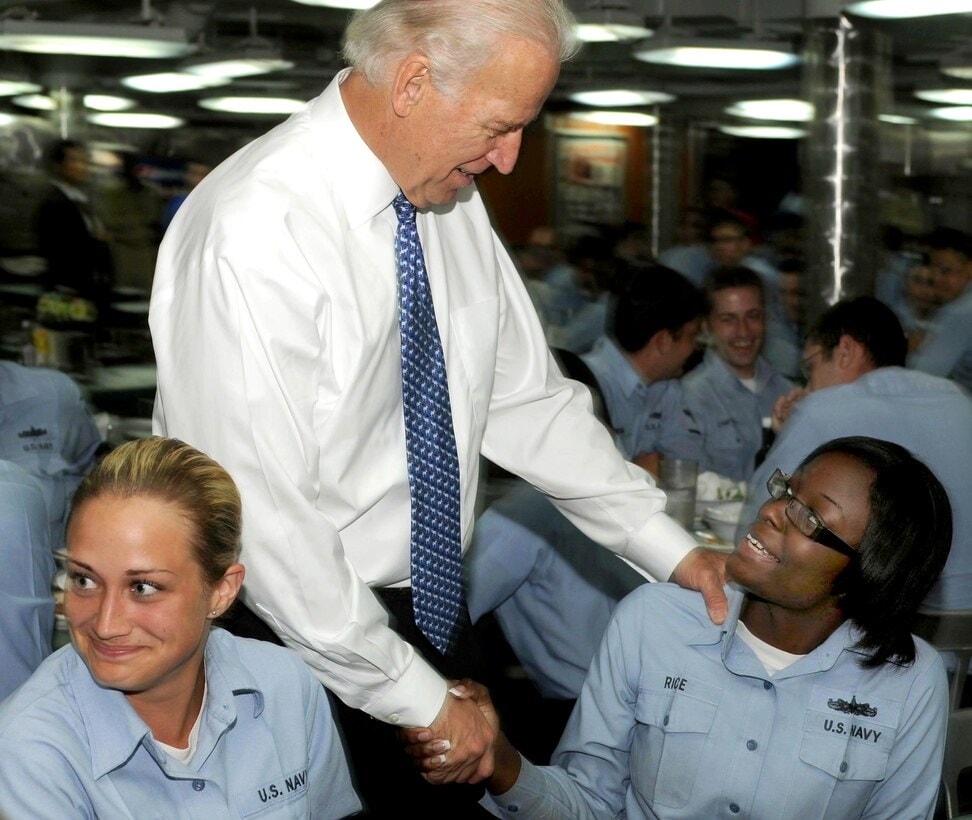

COVID-19 has impacted the way medical college students acquire hands-on experience, including the famous doctors’ rounds that can no longer take place. This video (dated May 2020) shows what happened as a result of the first pandemic wave. The second wave is likely to call once again for greater reliance on digital technology and renewed restrictions, as shown here:

New York, the place first hit by the pandemic in the U.S. was also among the first to take action to expand the number of healthcare professionals. At the urging of its medical students, New York University offered early graduation for students in their final year so they could be placed at hospitals throughout the city. More than half — 69 of the 122 fourth-year students — took on the offer. At least 24 other schools, including Rutgers and Harvard, have followed suit, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges.

In terms of COVID-19 educational impact in other countries, a similar approach was adopted in the United Kingdom: it was thought that releasing final-year medical students before the conclusion of their clinical examinations would help the healthcare system cope with the ongoing crisis.

Italy is moving even further in the same direction. On 17 March 2020, the Italian government passed the Cura Italia decree which changed the rules of Italian medical board examinations, fast-tracking medical students from all medical schools into the healthcare system after graduation, without having to go through the postgraduate examination which normally concludes the practical training. This change is permanent.

The new system shortens the process by about 9 months. It means almost 10,000 newly graduated medical doctors are qualified to join the healthcare system, potentially a hefty 10% increase in hospital doctors, supporting departments, and ICU dedicated to COVID-19 treatment in all parts of the country.

While these new doctors join the workforce during the pandemic, the shift from medical school to clinical work without a transition period potentially puts graduates at a greater risk of work-related stress. Only time will tell how well the new system works.

Low- and middle-income countries face similar difficulties and can be expected to make choices in pursuing policies making it easier to activate health professionals. What we now know is that the pandemic is not slowing, making the needs greater and more urgent. At the same time, the numbers of public health and clinical health workforces are likely to decline.

The pandemic will take a toll on schools and the number of students coming to be trained. It is likely that fewer students will be trained and some schools will be forced to close due to lack of funding. This will be coupled with the difficulty of replacing health workers due to mortality and burnout.

Health workers have also been refusing to work or resigning when there is insufficient protection from the virus.

For example, in March 2020, Dr. Kameliya Bachovska from the Second City Hospital in Sofia and 6 other colleagues handed in their resignation after they were informed their hospital would be converted to take in COVID-19 patients. “The hospital does not have enough protective gear, and it is not just our hospital that doesn’t. The rest also don’t have it,” she said, adding: “almost every doctor in Bulgaria is at risk of falling sick because of this, especially among us, the older doctors, who fall into the high-risk category”.

Bulgarian doctors however are not a special case. There are many other instances in which health workforce personnel have felt necessary to act to avoid contracting the virus when a hospital or other institution fails to take their risks into account. Failing to do so has led to a high infection rate among frontline health workers.

Reduction in these critical specialists is likely to be deeply felt in low- and middle-income countries at a time where their populations are growing. With the COVID-19 pandemic accelerating almost everywhere, the impact on the size of the health workforce and on educational institutions becomes a critical concern. And yet, the willingness of many governments to provide funding for such purposes has been hampered in many places by growing political “antiscience” movements.

How COVID-19 Disrupts the Education of Physicians and Veterinarians

A closer look at the educational pathways of physicians and veterinarians reveals the obstacles resulting from the pandemic and what needs to be done to remove them.

Physicians

During the typical course of study in medical school, clinical pathways in the curriculum put students in clerkships, which are healthcare rotations in hospitals, ambulatory settings, or the community, designed for students to acquire clinical care knowledge, skills, and professional values. This trajectory has changed with the COVID-19 virus disrupting routines in medical schools, clinics, hospitals, and beyond.

This has resulted in the cancellation of in-person medical classes, with most being replaced by recorded lectures or live-streams.

Among the significant losses is that of the benefits from in-person sharing of collaborative experiences, the real-time feedback, and back-and-forth that develop in a class setting, not available in online forums.

That said, to some degree small group case-based learning and team-based learning through webinars and teleconferences can substitute for face-to-face opportunities.

The need to minimize personal interactions is closely tied to mitigating and containing the spread of COVID-19. It is the underlying reason to decrease the risk of exposure concerns for students in a clinical setting, albeit many students often express readiness to put themselves at risk. And when the availability of personal protective equipment is uncertain and there is no adequate assurance of such protection, medical schools have canceled clerkships in order to reduce the risks.

But there is a silver lining. Integrating technology into medical education is a pathway for students to develop skills and improve adaptability. As a result of the new COVID-19 environment, faculty and students familiar with technological tools, are likely to think outside of the box and alter pre-conceived notions of how medicine should be practiced.

Such adaptability will be essential in meeting COVID-19 and unknown future epidemics and pandemics.

Veterinarians

Among other factors, the COVID-19 pandemic has forced veterinarians in the U.S. to carefully and judiciously consider their circumstances. The disease has affected practicing veterinarians as well who have “pivoted” quickly, adopting, inter alia, a wide range of precautionary measures and over 30% are using telemedicine to continue to offer assistance.

A fundamental point needs to be highlighted: Academic curricula for physicians and veterinarians are nearly identical relative to foundational sciences and clinical medicine and surgery course work. This means that some merging is possible – and with merging, comes the possibility to expand the educational offer to many more students.

There are, of course, distinct differences that remain. Yet, arguably, such differences open windows of opportunity. The possibility arises of significant crossover benefits from interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary collaborations. Such crossover benefits take on added meaning and weight if one adopts a One Health lens to view disease.

Need for a One Health Approach to Handling Pandemics

Make no mistake, COVID-19 is only one of many such viruses and other pandemics are likely. A One Health approach calls for pulling together human, animal, and environmental factors to arrive at faster, better preventative and control modalities. As a result, fighting the likely impending onslaught of zoonotic pandemic diseases like COVID-19 now and in the future, requires giving far greater consideration to institutionalizing a OneHealth approach. And that includes establishing extensive education and collaborative research efforts between human and animal doctors.

The third component of the One Health, approach namely the environment, has also become a visible element of this aerosol COVID-19 pandemic and will become increasingly so in the future. It too requires heightened education and research funding attention.

Country and global leadership must proactively think and act holistically, dedicating resources to research and teaching in universities and at all institutions of higher learning, so that the interconnection between people, animals, [plants], and their shared environment is recognized—thus significantly contributing to our future well-being. Indeed, as all One Health supporters and advocates know, One Health implementation will help protect and, for those who get sick, save untold millions of lives in our time and for future generations.

EDITOR’S NOTE: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. In the featured photo: Learning on a screen. How Medical Students Are Adjusting To Hands-Off Learning Amid COVID-19 Photo credit: NBC News NOW 27 May 2020 (screengrab)