I was first introduced to the impact economy while working at the Vancouver Economic Commission (VEC) in the summer of 2016. At the time, VEC held an event where businesses working in the impact sector were invited to tell their stories and dispel myths about their work. Two things that were said at the event stood out to me then and have driven my interest in the impact space ever since:

- Firstly, that it was possible to be driven by both purpose and profit. These organisations were oriented towards producing a clearly defined social or environmental benefit (e.g. lowering greenhouse gases, creating opportunities for those with barriers to employment), while at the same time having some form of profit motive in doing so.

- Secondly, that it was possible to achieve a profit at all while still having a purpose. All of these organisations were not only interested in making a profit, but also there on the stage because they were currently succeeding in doing so.

These observations helped me to form an initial understanding of the impact economy and the reasons why governments have a crucial role in helping to promote it.

What is the “impact economy”?

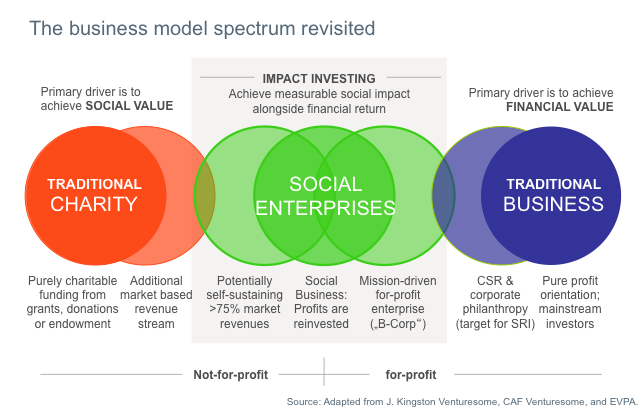

The “impact economy” has been challenging to define, and is often mistakenly said to simply encompass traditional companies that have an explicit corporate social responsibility (CSR) strategy. However, it extends far beyond that. Ultimately, the business of the impact economy is conducted by entities which are deeply and equally focused on both profit and purpose. This generally includes social enterprises, the social economy as a whole, benefit corporations, charities with business ventures, and companies that otherwise have an explicit and embedded commitment to a “triple-bottom line”: this refers to considering the social and environmental impacts of the firm’s business activities on top of the traditional financial bottom line. Despite this diversity, ‘impact’ is used as a convenient catch-all phrase which lumps together this wide range of actors with different motivations and activities.

Read more: Social Entrepreneurship: The Case for Definition (SSIR)

Over ten years ago, Roger L. Martin and Sally Osberg argued in the Stanford Social Innovation Review that there needed to be a proper definition for social entrepreneurship. Their ideas are still relevant today when conceptualising the impact field. Martin and Osberg spent some considerable time sussing out the foundations of both entrepreneurship and its social variant, but ultimately argued that the latter is inseparable from the former. For them, social entrepreneurship comprises of three parts: (1) identifying ‘a stable but unjust equilibrium’; (2) identifying a social value proposition to upend this unjust equilibrium; and finally (3) creating a new stable equilibrium through scaling of the disruptive activity(s).

However, must impact always scale? This question of whether social or impact ventures must scale provoked great disagreement then, and continues to raise considerable ire today. Kevin Bayuk of Lift Economy recently offered an interesting bridge for those on either side of the divide. He referenced the overarching mission of all such ventures to increase the overall strength of the network(s) within the impact sector. Individual scalability is, for him, a red herring; what matters is whether the sector is able to ‘federate’ and share resources, ideas, and capital in a networked manner. Thus, under this view, scale and locality need not be mutually exclusive.

Read more: Kevin Bayuk: Our Journey to an Economy that Works for the Benefit of All Life (*Episode 100!*)

To have a holistic view of the impact economy, it is important also to include the role of investors, who may be impact businesses themselves or enablers on particular, and sometimes ad-hoc, bases. Impact investing is a crucially enabling force for all types and scales of impact organizations, either through the direct contribution of capital by investors, or through their impact-aligned demands of existing assets they hold (e.g., through shareholder activism).

Clearly So offers a crisp, yet holistic view of this in their definition: “Impact investing means considering risk, return and impact when making investment decisions, and choosing to invest in companies that are actively creating positive social or environmental impacts.” Ultimately, this varied collection of organizations and ideas — charities, social ventures, B-corps, and many others — and, crucially, the flow of capital into them, collectively make up the “impact economy”.

How does the Public Sector view the Impact Economy?

When I first started working in the public sector, I had never heard of the impact economy before and neither had any of my colleagues. Yet, there is a historical connection between these two areas that is only growing stronger in the present. Janelle Kerlin’s research suggests that the absence of government social spending in the 1970s and 1980s helped create the impact sector in the first place, or at least spurred its growth. When I see the public sector engaging with the impact sector today, it is generally for two overarching reasons:

- It is seen as an innovative way to deliver on services in a political climate where even modest taxation increases are hugely unpopular with the electorate;

- It extends positive social, economic, and environmental benefits into sectors, or individual communities, at a previously unattainable scale..

With the scale of challenges posed to us — climate change, income inequality, decolonization and reconciliation — governments lack the resources to handle the sheer breadth of challenges (and opportunities) that are emerging. The demands of them are simply too great. Yet, despite the increasing deficiencies in some impact-related spaces, the most interesting calls for public sector activity and investment in these areas are strategically proactive, not defensive, in nature.

Institutions such as Lift Economy, Renewal Funds, ESME, and many others have developed approaches and justifications to support and grow the impact economy, because they see its transformative potential as a channel to change existing power structures. Many of these actors see an opportunity to utilize particular market mechanisms as a way to build economic democracy, increase local resilience, create self-sufficiency amongst marginalized communities, and to create models of rehabilitative or restorative activities (particularly in the ecological space) which they are attempting to grow to be widespread, market-based activities.

Any one of these aspirations would be worth considering seriously on its own, but the range, complexity and sheer diversity of these opportunities are especially notable. As the founder of Lift Economy has noted, the step-change possible with the impact economy is that when these initiatives are coordinated, they can scale and federate, recursively creating greater resilience and impact. Therefore, having direct, meaningful public sector support for the impact economy makes sense on two fronts:

- Ensuring the ongoing, sustainable provision of basic public good(s); and

- Building momentum and taking action from multiple vectors to create more resilient, just, sustainable, and inclusive communities.

However, it is important to note that the growth of the impact economy is no panacea to social or environmental ills. There remains an irreplaceable role for governments in a number of areas for social, economic, and environmental regulation, protection, and investment. But at the same time, as the scale and complexity of our world grows, building inclusive, resilient coalitions that can help provide social good(s) can and should be seen as a significant policy priority.

Public Sector Support for the Impact Economy

Efforts that the public sector can take to support the impact economy fall into a few key areas: regulation, investment and procurement, taxation, education, and business and trade policy.

(a) Regulation

- Creating standards and verification systems that allow investors and consumers to understand and differentiate impact products.

- Clarifying and strengthening the concept fiduciary responsibility for trustees and financial managers in order to ensure that impact investments are not only seen as useful and viable, but that they actively support their responsibilities.

- Creating a supportive reporting and monitoring system, including mandatory disclosures for things like Environmental, Social, Governance (ESG) factors, or climate risk.

(b) Investment and Procurement

- Use existing public sector financial institutions, including pension plans, sovereign wealth funds, export banks, and national and international development banks, to prioritize impact investment.

- Creating new, specifically targeted government funds to drive impact investment.

- Creating binding impact-based procurement strategies for all types of public sector bodies.

(c) Taxes

- Prioritizing and supporting impact businesses through preferential taxation policies.

(d) Education

- Ensuring that all stages of the education system are preparing students both to create, support, and invest in impact businesses and an impact ecosystem at all scales.

(e) Business and Trade Policy

- Adapting existing business support structures, like export commissions and venture acceleration networks, to support the impact economy.

- Pursuing international trade agreements that raise the bar between countries on impact factors such as inclusion and the environment.

The Way Forward

Governments may decide to support the impact economy for a variety of reasons. These range from capitalizing on voters’ interest in this area of economic work, to meaningfully diversifying the economy and strengthening community resilience. When I look at my friends and colleagues making positive change in the world, I am encouraged to see that many of them now do so as part of coalitions of public, private, and non-profit actors. As our world and its problems grow ever more complex, having more of these coalitions — and having more sustainable, flexible, and networked institutions devoted to social and environmental good — can only be a good thing.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter’s columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com.

Featured Photo Credit: Photo by Ross Findon on Unsplash