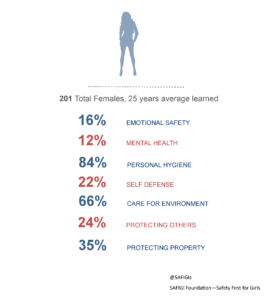

For every 6 in 10 South Sudanese males who have learned about mental health and emotional safety in their secondary education, zero South Sudanese girls had access to the same. The study featuring 29 South Sudanese found half the girls had learned about personal hygiene, 1 in 10 had about environmental care, while none of the girls had learned about self-defence, protecting others, protecting property, mental health or emotional safety during their secondary school education. (SAFIGI, 2017)

“Education is the key to success” is the mantra I was taught – gathering red dust on my discoloured white socks as I walked hours on a lonely road to school at six years old in a remote town of Zambia – just to learn my ABCs. What is success? I ask myself, one Summa Cum Laude later.

IN THE PHOTO: Empty classroom in Zambia. PHOTO CREDIT: SAFIGI

The system of education remained patriarchal until the Women’s Rights movement in the late 1900s for the western world. The school curricula as we practice it began in 1837 in Massachusetts though we can credit formal style of learning to Mesopotamia (Egypt). Early education was more informal, with boys learning trade from their fathers or taking up apprenticeships and girls cooing at their mother’s ankles to practice housekeeping and cooking.

It is no wonder that in 2017 84 percent of girls had learned personal hygiene during their secondary education (SAFIGI, 2017).

The latter is not a bad fact. It only proves the shortsightedness of our current education system when we see only 24 percent of girls had learned about protecting others, 35 percent about the environment and 12 percent about mental health as of 2017.

If our current education system is not updated to match our evolving world, then the fight for gender equality and equity will remain much like the mantra I recited at school – “education is the key to success”. A well-intended and otherwise vain promise.

IN THE PHOTO: Students in a class. PHOTO CREDIT: SAFIGI

Education is pivotal to give girls a fighting chance in a grossly patriarchal world; to increase their opportunities, end child marriage, teen pregnancy and Female Genital Mutilation, for example. The education gap still exists and it is critical to ensure girls are given equal opportunity to get in and remain in school. This cannot be debated. However, one of the consequences of our current education system is it is doing away with much of informal learning.

Parents spend more time working and students spend at least nine months a year at school. This transfers education about life to institutions and peer-to-peer learning, which may not be the most informed advice for a girl. Thus, any information that is not instilled in the school setting may never be learned and that is where survival instincts to navigate the real world come into play.

What is the real world anyway?

A real-life case study we encountered during our data collection in Zambia paints the picture better than any numbers could.

“In 2007, Linda compound of Livingstone Zambia, a respected elderly widow in his late 70s implored girls within the community to assist him with household chores for handsome monetary rewards. A few months on, a vicious rumour made rounds that two notable teen girls, singled out to help the man, were not only house helpers but in fact, having an intimate affair with him. The girls, both in 8th grade at a named basic girls school, were between the ages of 13 and 14. (Case in mind, 8 in 10 girls learn personal hygiene during their basic education).

Angered by the news some members of the community decided to take anonymous action. They were afraid to approach the old man directly or report to the police in fear that the old man might be a wizard and in the case their identity is known, they would be bewitched. The inappropriate sexual relationship was reported to the institution in hopes the school will take disciplinary action and ban the girls from going to the old mans’ house.

The school administration went on to summon the old man and he denied accusations, vehemently demanding justice from those who started the rumours. The girls also denied the relationship, perhaps out of shame and lack of trusted confidants. The case was dismissed without any resolution.

Months later it became apparent that the girls had in fact been having a sexual relationship with the old man as both teens were pregnant. The old man paid their families in a promise to sponsor both girls so as not to be reported to the police. Meanwhile, the girls dropped out of school. He married one of them and they are still living as husband and wife to date.”

IN THE PHOTO: Zambian teen mom. PHOTO CREDIT: SAFIGI

Education is defined as ‘the process of imparting or acquiring general knowledge, developing the powers of reasoning and judgment, and generally of preparing oneself or others intellectually for mature life’ according to dictionary.com.

In a study that spanned six countries including Zambia, Egypt, Tanzania, USA, Namibia and South Sudan, and 452 total respondents, SAFIGI Foundation set out to unearth ‘Core Issues Affecting Safety for Girls’. Safety is a broad term and for this study, we narrowed to Safety Education.

Safety Education is defined as the practice of internal and external safety. Internal safety is peace of mind, heart, emotions and external safety is the protection of the body, other person, and environment. (SAFIGI, 2014).

In this scenario, we see how flawed the education system was in preparing girls for real-life situations – both emotional and physical. There is also an in-bred silence when it comes to speaking out because of systematic oppression and family dynamics. We found that 9 in 10 people ‘did nothing’ about domestic abuse they faced.

SAFIGI Researcher, Ms Steffica Warwick, in her research paper titled ‘Silent Voices: Violence Against the Female Body as a Consequence of Machismo Culture in Latin America’ writes; “According to the Colombian Institute of Family Welfare, minors have typically been viewed as inferior, passive and property of the father. This position can easily be exploited by authority figures in positions of power, such as family members, teachers or any older male that a young girl might frequently be in contact with. As a result, the overwhelming majority of perpetrators are father figures.” This also proves that the concern, as in the case study, is not restricted to the region.

IN THE PHOTO: Chart: how much girls learned in school. PHOTO CREDIT: SAFIGI

Systematic and biological differences have to be factored in when educating girls. If equity is not employed in education, inequalities, injustices, and oppression of girls will continue unchecked. Safety Education can fill these education gaps and will result in healthier communities, higher life expectancy, improved access to health, gender equality, and safer communities. (SAFIGI, 2017)

The world we live in is affected by the visible and the invisible. When pertaining to safety, what happens in the mind, emotions, or heart affects the external well-being of the person, other people and the environment.

What happens on the outside also affects internal perceptions. These differences cause conflict within self and this also affects others. Education about self-awareness and awareness of others and the environment empowers girls to recognise predatory behaviour even in themselves or others and gives girls the tools to recognise and fight oppression from the onset.

The better part of this education is that its standards of internal and external safety remain the same regardless of one’s background, culture, religion or environment. This also gives girls who have not had the opportunity for formal education an opportunity at rehabilitation and recognising the factors affecting their worlds.

Girls who have not had formal education, girls fleeing conflict or combating various mental health issues can benefit from Safety Education because it gives awareness to the core issue affecting their safety and not just the visible side effects.

In a research by Ms Shucheesmita Simonti on “Gender-Based Violence and Subsequent Safety Challenges of Rohingya women”, she writes; “It is essential to adopt a gendered analysis of human security to understand how gender-based violence impinges upon the notion of human security. According to the UNDP report 1994, there are seven types of localised security threats: economic, food, health, environmental, personal, community and political.”

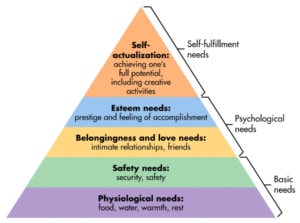

Core issues affecting girls can also be pinned in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. The current education system aims for self-actualization without directly responding to the safety and security needs. Due to the changing nature of our world, intrinsic knowledge of self and the current environment is imperative for wellness, health and gender equality.

IN THE PHOTO: Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

In a grievous story of the two girls, we see how the family dynamic, education system and society itself was helpless before, during, and after abuse took place. The young girls are victims of the system and the cycle will continue if there is no drastic change to their education, even if they do not go back to school. In such a case, Safety Education can help the girls recognise the abuse done to them and take healing steps to fight for their rights and employ their skills entrepreneurly.

In a Safety Workshop SAFIGI Foundation hosted at the University of Zambia, we found that all participants registered more understanding on conflict resolution within self and others. Formal education may offer an opportunity to earn a certificate which could lead to employment but it is crucial to realize that the world’s problems go beyond getting a job. Who is preparing our girls for this reality?

German philosopher Josef Pieper said of work: “Of course, the world of work begins to become – threatens to become – our only world to the exclusion of all else. The demands of the working world grow ever more total, grasping ever more completely the whole of human existence.’

Thus when education focuses only on the concept of employment, the true lessons of human dignity and social cohesion are neglected. The much-needed fight for equal pay between the genders emphasizes work for women as a key to socio-economic development at individual and national levels.

This fight must also extend to transformative education for girls because even with the same qualifications the opportunities and risks are gendered in nature. Girls need to be empowered to change the narrative and form a more just and equal society through holistic education. This is even more crucial for girls of color, refugees, and queer society.

“In case of personal security, Haq (1994) also draws attention to gendered dimensions of personal security – ‘Among the worst personal threats are those to women. In no society are women secure or treated equally to men. Personal insecurity shadows them from cradle to grave. In the household, they are the last to eat. At school, they are the last to be educated. At work, they are the last to be hired and the first to be fired. And from childhood, through adulthood, they are abused because of their gender.’” (Simonti, 2017)

Safety is gendered in nature because similar circumstances can play out differently based on a persons’ gender. And as much as Women’s Rights movements and activism has made strides for women, the grassroots are still wallowing in the patriarchal oppression. Even beyond the burden of toxic masculinity, education is only preparing girls to attain qualifications and does not cater to the need to understand self, understand the world, and understand one’s place in it. Adding these issues may seem like a lot to ask for an education system that is already burdened with more graduates than society has jobs, and maintaining a set standard of measuring intelligence for 7 billion unique people. While we cannot ignore the strides in humanity as a result of education, we have to allow the system to evolve in order to accommodate the needs of present day.

The standard of education is not actively evolving to meet the demands of our changing world. Mental health, climate awareness, financial intelligence, physical safety, technology, and internet remain outside the main curricula and are mostly taught only in privileged settings. Education is the key to success, and yet if after 12 years of school I have not learned how my mind works, the parameters of my emotional intelligence, heart health, body awareness, living with others, and the environment, then I am disadvantaged for Maslow’s self-actualization.

9.6 in 10 people believe Safety Education is relevant in our society and until we see it as a practical way of life, gender equality, equity and robust wealth will remain a privilege.

Editors Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com FEATURED PHOTO: Young girls. PHOTO CREDIT: SAFIGI