The challenges confronting the new EU Commission, as laid out in the Letta and Draghi Reports, are substantial and multifaceted. The message in both reports is loud and clear: Europe risks falling behind the United States and China, particularly in critical areas like AI development due to underfunding of research, insufficient computing power, and a failure to leverage the scale of the European economy.

Both the Draghi and Letta reports completely align with the assessment of most international experts, the latest coming from Michael Spence in a remarkable analysis published by the IMF this September. It’s worth noting that Spence is not a European economist but a renowned American who was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 2001 and is presently Philip H. Knight Professor and dean, emeritus, at Stanford Graduate School of Business. One cannot imagine a higher accolade from academia, and yet, as I will try to show here, it is remarkable how both the Draghi and Letta reports fell on deaf ears.

Enrico Letta’s April 2024 report to the EU Commission, “Much more than a market,” highlights the need for strategic investments in a fair green and digital transition, EU enlargement, and enhanced security. Specifically, the EU should:

- Commit to a fair, green, and digital transition, noting that the upcoming legislative term is crucial for ensuring its success – indeed, this will be EU president Ursula von der Leyen’s next big challenge;

- Pursue enlargement: This is a complex process that will require careful execution and setting a “clear direction” for integrating new members;

- Enhance EU security: This is seen as particularly crucial in a world of growing systemic instability, requiring more demanding positions and decisions in defense. Thus, it responds to both French President Macron’s repeated demand for the establishment of a modern, coordinated European-wide defense system and to the wishes of around 77% to 87% of European citizens, according to recent surveys.

Letta notes that these goals represent a significant departure from the past, as the Single Market was initially conceived in a different, simpler era with less complex challenges. He points out that the EU urgently needs to move away from the past.

If not, Europe risks being sidelined by history as both China and the US surge ahead.

Mario Draghi’s report to the EU Commission on the European Competitiveness: Looking Ahead is even stronger: It is a clarion call to wake up Europe. And quite frankly, if his report doesn’t wake up Europe, nothing will. It aligns fully with the Letta Report, calling for the full implementation of the EU single market, including a Savings and Investment Union to enable the free movement of capital across the bloc.

As Draghi himself told the European Parliament four days ago when he presented his report: “Europe faces a choice between exit, paralysis, or integration.” Think about those three words: Europe can either:

(1) leave the geopolitical scene to the US and China;

(2) become economically stagnant and politically dormant; or

(3) unite to achieve strength and equal power with its rivals.

Which one will it choose?

In his speech to the MEPs, Draghi focused on several major themes:

- a unified response to Russia’s war on Ukraine;

- a deeper European integration;

- sustainable and secure energy solutions for Europe, highlighting that EU businesses face energy bills that are three times higher than their competitors in America or China;

- increased investment in innovation and infrastructure, especially in AI, to boost European competitiveness.

Unquestionably, that last one was Draghi’s most striking point: Innovation in Europe is “blocked.” Historically, Europe, the cradle of the Industrial Revolution, was at the forefront of technological inventions. No more. As he noted in his report:

“…we are failing to translate innovation into commercialisation, and innovative companies that want to scale up in Europe are hindered at every stage by inconsistent and restrictive regulations. As a result, many European entrepreneurs prefer to seek financing from US venture capitalists and scale up in the US market. Between 2008 and 2021, close to 30% of the “unicorns” founded in Europe – startups that went on the be valued over USD 1 billion – relocated their headquarters abroad, with the vast majority moving to the US.” (bolding added)

He concludes: “With the world on the cusp of an AI revolution, Europe cannot afford to remain stuck in the “middle technologies and industries” of the previous century. We must unlock our innovative potential.”

But his recommendations don’t stop there. He also calls for addressing two other critical vulnerabilities that threaten Europe:

- The energy price gap faced by European industry compared to rivals with much lower energy bills: The solution is “a joint plan for decarbonisation and competitiveness” with the aim to bring the benefits of “clean energy” to all European end-users, businesses, and consumers alike; as explained in the report, the challenges are: “Market rules [that] prevent industries and households from capturing the full benefits of clean energy in their bills. High taxes and rents captured by financial traders raise energy costs for our economy”; what is needed is to “transfer the benefits of decarbonisation to end-users” and turn “clean energy” into a “growth opportunity for Europe” by resisting the allure of cheaper energy solutions offered by China: They are state-subsidized and constitute unfair competition;

- The risk of rising insecurity “as the era of global geopolitical stability fades” and over-dependence on global supply chains that can be disrupted at any moment; the solution is two-pronged, and we need:

-

- A “genuine EU ‘foreign economic policy’” to coordinate preferential trade agreements and direct investment with resource-rich nations, build up stockpiles in selected critical areas, and create industrial partnerships to secure the supply chain of key technologies;

-

- A strong defense industry: now it is “too fragmented, hindering its ability to produce at scale, and it suffers from a lack of standardisation and interoperability of equipment, weakening Europe’s ability to act as a cohesive power.” Anyone who doubts fragmentation is a problem should consider this: For example, twelve different types of battle tanks are operated in Europe, whereas the US produces only one.

Overall, implementing Draghi’s policy recommendations will require that the EU significantly increase its investment, particularly in areas like innovation, industrial policy reform, energy independence, and decarbonization1. While the exact figure isn’t specified in the summaries, it’s clear that the scale of investment required is substantial to meet these ambitious goals.

As Leo Donnachie, Senior Policy Manager for Sustainable Finance at IIGCC (a pan-European investor group founded in 2001 and focused on responsible investing) wrote in an insightful analysis of Draghi’s report:

“Critically, the transition to net zero is identified as one of the central drivers of the EU’s future economic growth and competitiveness. But to capitalise on the opportunities presented by the transition, Draghi emphasises the need to pursue the goals of the Green Deal in tandem with innovation, re-industrialisation and boosting resilience. The proposals provide a comprehensive basis for the development of a “Clean Industrial Deal,” which von der Leyen has committed to progressing in the first 100 days of her second mandate.” (bolding added)

Indeed, the “Clean Industrial Deal” will need to be funded as a priority. Draghi told the EU parliament that “a fit-for-purpose competitiveness agenda would require annual funding of between EUR 750 – EUR 800 billion for projects whose objectives were already agreed upon by the EU.”

Donnachie notes that despite the good business case Draghi makes for prioritising the decarbonisation of hard-to-abate sectors, public policy support remains limited. Yet the investment needs will be massive: Draghi estimates it will require some €340bn over the next 15 years to decarbonise the four largest carbon-intensive sectors in the EU (chemicals, metals, non-metallic minerals and pulp and paper products), and €500bn over the period 2025-2040.

Clearly, without strong public support, especially at the national level, nothing will happen – which is why, as I will try to show in the next section, it is a matter of concern that, with the notable exception of the above-mentioned IIGCC article published two days ago, the overall public response so far has been muddled and weak.

Public response to Draghi’s Report: The Media

Despite its loud and clear call for action, Draghi’s report didn’t get the attention it deserved from MEPs, the press, or the public.

It is difficult to fathom why this happened. Perhaps it was unfortunate timing—the Report came out on September 9, just as Brussels began to be roiled by political maneuvers around the EU Commission when Ursula von der Leyen tried to pull together her team for her second mandate.

Media outlets like POLITICO got caught up in the palace intrigues. They became more focused on internal EU power struggles and personalities than on the substantial policy challenges raised in the Draghi Report. No doubt, calling the Commission President “Queen Ursula” and “Empress Ursula” and accusing her of power-grabbing makes for a more “fun read” and is a sure click-baiter, attracting readers.

This focus on palace intrigue rather than substantive policy debate hinders progress and could have dire consequences for the future of the EU.

In the European Parliament, the reaction appeared to follow the usual party lines. Most MEPs in the center and left of the political spectrum agreed with Draghi’s analysis and proposals. At the same time, those who disagreed, arguing that any decarbonization plans to fight climate change would sabotage the economy and that any move toward EU-wide policy coordination would threaten national sovereignty, were (predictably) on the right, conservative end. They merely voiced the classic arguments advanced by corporate interests and the fossil fuel industry to defend their bottom line.

The press’s reaction was equally predictable. Bloomberg, in one article, doubted that Draghi’s recommendations could lead to any concrete steps given the complexities of the European political situation, pessimistically concluding that “the eurozone’s competitivity crisis has too many moving parts for a straightforward fix.” The Financial Times, while it tried to highlight the more substantive issues, concluded with an equally discouraging comment: “Politics will be a sticking point.”

The general public reaction

Two days ago, Euronews reported that Draghi’s report was “slammed as being one-sided “ and that various stakeholders were accusing him of “not including voices from all parts of Europe in his landmark report.”

According to a list published by the European Commission, Draghi’s team received 236 contributions — in writing or meetings — from think tanks, universities, lobbyists, EU bodies, trade and business associations, and some NGOs. Prestigious Brussels-based research institutions, big tech companies such as Google and Amazon, the European Central Bank, and top non-EU universities such as the London School of Economics or Harvard were contacted.

However, some reportedly noteworthy stakeholders were not consulted. “Not a single Central and Eastern European personality has been questioned by Draghi’s team about the desolate state of Europe,” said Velina Tchakarova, a Vienna-based geopolitical consultant, in a post on X:

Not a single Central and Eastern European personality has been questioned by Draghi’s team about the desolate state of Europe nowadays. Once again, we are becoming an object of someone else’s fate and wrong decions. #Velsig #geopolitics https://t.co/77WYMLa7Bb

— Velina Tchakarova (@vtchakarova) September 18, 2024

Yet, as the Euronews article noted, criticism is spreading as civil society organisations and NGOs complained that their views were not taken into consideration. Olivier Hoedeman, Corporate Europe Observatory’s research and campaigns coordinator, told Euronews that civil society and trade unions account for only 5% of the contributions to the Draghi report. He concluded: “With such a one-sided process, it [the report] fails to adequately address the scale of the ecological crisis and social inequality in Europe.”

Maybe. But one may well wonder how he arrived at that 5% figure. In any case, the report takes the ecological crisis and social inequality in Europe as a premise for the analysis and search for solutions: Nowhere does Draghi argue that the ecological crisis is unimportant or that social inequality doesn’t exist. But he does start with data and not with opinions about inequality: For example, here is a diagram included at the start of his report (page 8) which shows income and wage inequality in the EU compared to the rest of the world (it’s worth noting in passing that this also shows the EU is at present the least unequal society in the world):

Another case in point: the European Environmental Bureau (EEB), listed as a contributing stakeholder, told Euronews it was not involved in the process, despite requests to meet Draghi’s team. “Had the EEB been consulted, we would have stressed the importance of ensuring that President von der Leyen’s Clean Industrial Deal does not become a deregulation agenda,” said EBB Secretary General Patrick ten Brink.

Just to be clear: Nowhere in his report does Draghi argue that the Clean Industrial Deal should be deregulated or set aside. On the contrary, he draws a path to strengthen it, clearly indicating what is required to make it a reality.

But more to the point: Why should Draghi’s report be a compilation of everyone’s views?

That was not his mandate: President von der Leyen commissioned a report to get his views, not to get an overview of what everyone thinks or wants in Europe. That is the job of the Standard Eurobarometer surveys that regularly record the views of European citizens on a wide range of topics. In this case, she wanted Draghi’s opinion just as earlier, in April, she had gotten Letta’s views.

Draghi is entitled to his views, and that is precisely what his report reflects. Indeed, a Commission spokesperson said on Friday that since Draghi was mandated as an independent special advisor, “it was up to him to choose his working methods and consultation process.”

How he formed his opinions is his own business. As a former head of the European Central Bank who achieved fame as the savior of the Euro, I believe he should be credited with knowing how to analyze an economic situation and arrive at realistic, evidence-based solutions.

We should be discussing his proposed solutions and how to implement them, but that is not what is happening.

Instead, we are wasting time in pointless discussions. One is reminded of the historical anecdote that the Byzantines, under threat from the Ottomans, engaged in theological discussions about the sex of the angels rather than figure out how to defend themselves. As historians later proved, this was not quite the case as they managed to set up defense systems even though they proved insufficient against the might of the Ottoman army.

Likewise, Europeans will hopefully find a way to stop quibbling and set themselves to the task of turning around the European economy, as Draghi proposes.

Unsurprisingly, Draghi’s office did not respond to Euronews’ request for comments. However, Draghi’s proposal undoubtedly has a problem: its cost. Financing it will require considerable public funding, which could prove politically impossible, as explained in the next section.

How to fund the competitiveness agenda: The real reason why Draghi’s proposal is getting the cold shoulder

Let’s be clear: A fit-for-purpose competitiveness agenda will be very costly. As mentioned above, it would require at least EUR 750 to 800 billion yearly—if not more. That’s about 5% of the EU’s GDP.

Where will the funds come from? Some could come from private sector investors, but some would also need to be secured through public investment, including, as Draghi told the European Parliament, a new common debt issued specifically to fund key joint projects.

And this is the problem: the “common debt.” This is where the sovereignty fixation that plagues Europe rears its ugly head: The German Minister of Finance, upon reading Draghi’s Report, was quick to react, declaring that any such new “common debt” was out of the question.

Unsurprisingly, his reaction deepened the divide within Germany’s coalition government. Some members supported Draghi’s vision for massive investment to boost competitiveness, while others remained firmly opposed to increasing joint debt. The proposal also received criticism from other countries, like the Netherlands, further complicating the European consensus on this issue.

The issue at hand is, in fact, the NextGenerationEU programme, which was set up for post-pandemic recovery. It offers member states grants and loans to make critical investments in exchange for targeted reforms, financed through—and this is a first— a “common debt,”i.e., jointly underwritten by EU member states.

Historically ‘frugal’ EU countries, including the Netherlands and Germany, vehemently oppose renewing NextGenEU beyond its scheduled expiry in August 2026. This looming battle is throwing its dark shadow over Draghi’s proposals and could very well put them to bed.

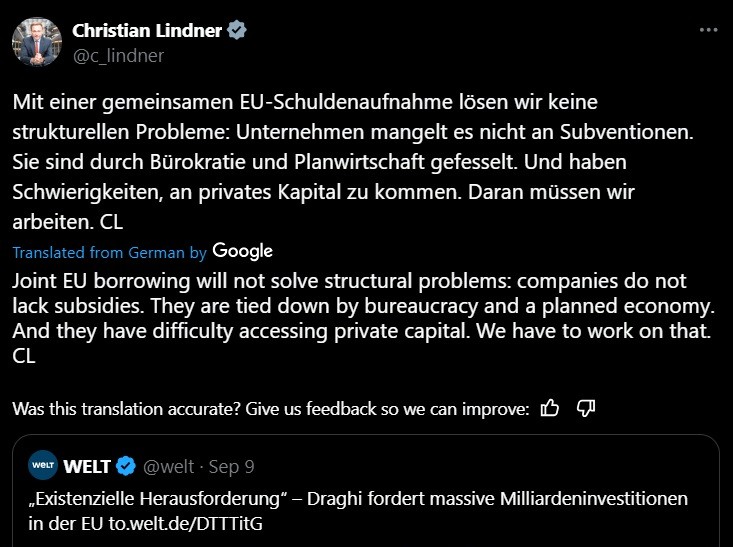

The German Finance Minister is Christian Lindner, leader of the pro-business liberal FDP, a pro-business politician, and the voice of corporate interests. He was adamant: “Joint EU borrowing will not solve structural problems: companies do not lack subsidies,” he wrote on X. They are tied down by bureaucracy and a planned economy. And they have difficulty accessing private capital. We have to work on that.”

The German Finance Minister is singing the same old Milton Friedman neoliberal tune: Private capital and the market can solve every “structural” issue we face, and any proposed investment from the public sector smells of a “planned economy” (read Soviet-style) and should be firmly rejected because public bureaucracy is inefficient.

This conveniently overlooks the fact that staff in big corporations is equally if not more inefficient since they couldn’t care less about their bosses’ profit-making. And what is “planned” about the German economy today, you may well ask? How can a German politician write this some 35 years after the fall of the wall of Berlin?

And yet, here we are, back to square one, throwing words at each other without listening to what the other has to say—and without considering the lessons of History: Milton Friedmanesque solutions of the kind Mr. Lindner supports are now amply discredited by the economic profession. They have only led to economic and political disasters, as the experience of Pinochet’s Chile and the Generals’ Argentina (among many others) have taught us.

A secondary issue is the pathway the EU Commission has followed to ensure that businesses will transit to sustainability: Its two directives (the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive and the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive) call for yearly sustainability reporting intended to inform both investors and customers of the progress made toward full sustainability.

Draghi argues that where the EU’s sustainability reporting and due diligence frameworks could be a source of regulatory burden for firms, they should be postponed in the name of maintaining competitiveness.

Interestingly, the above-mentioned pan-European Investors group IIGCC argues against “delaying – or worse, rolling back – the standards in place.” It views “the implementation of sector-specific standards [as] essential for helping investors understand specific climate-related risks and opportunities they are exposed to across individual sectors, as well as for companies seeking to better navigate their own exposures and impacts.”

Next steps: EU long-term budget 2028-2034

The Draghi Report recommendations are not legally binding, but the “mission letters” for the new Commissioners-designate, released on 17 September 2024, call on them to draw on the recommendations in the context of their missions. The expectation is that the process will move forward in the following months in the laborious way it always does in Brussels, with multiple-level dialogues engaging stakeholders.

Draghi’s proposed additional common EU debt will likely be intensely debated ahead of the next European Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF), which sets the EU’s long-term budget from 2028 to 2034. While dates for the meeting have not yet been announced, it is likely to begin in 2025 or 2026.

It is noteworthy that Draghi’s proposal involves not just coordinated, joint investing but also transferring risk to the public sector. He proposes increasing the EU budget guarantee component of InvestEU to reduce risks for public and private investors. In line with the EU Call to Action, he also proposes giving the European Investment Bank (EIB) a larger role in making it easier for investors to finance these investments and increasing its capacity to take on more risk.

To secure its future, the EU must undoubtedly prioritize investments in research and development, address fragmentation in capital and service markets, and foster a greater sense of unity and purpose among member states. Failure to do so could result in the EU falling further behind global competitors and struggling to maintain its influence on the world stage.

It is also true that Draghi’s report is focused more on strictly financial aspects rather than the transition’s ecological impacts.

Perhaps this could be expected from a central banker such as Draghi. And perhaps we shouldn’t worry too much about this oversight: Von der Leyen’s Commission is committed to pursuing the Europe-wide Climate Adaptation Strategy, adopted in 2021. This strategy aims to make Europe climate-resilient by 2050 and focuses on four main objectives: making adaptation smarter, swifter, more systemic, and stepping up international action on adaptation.

Small wonder that Draghi viewed climate resilience as beyond his remit and focused instead on economic competitiveness and resilience, which was the missing link in EU policies.

These are the facts.

QED.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Cover Photo: Mario Draghi addressing the European Parliament Source: image used on X post by Minister Christian Lindner on Sept 9, 2024 (detail)