Would you choose to buy a product if you knew it has been produced by slaves? Probably not; but reality is, in many countries around the world slavery still does exist. It is known as “modern slavery” to differentiate it from the slave trading that took place in North America between the 15th and the 19th century, but it has no difference. People including women and children are still exploited and involved in the textile industry, in plantations, constructions sites, and in the mining industry. Potentially, any product we use could have been, at some point, in the hands of a slave. This has nothing to do with a sustainable economy, and to raise awareness about the issue of “modern slavery” today we speak with Elise Groulx.

Elise Groulx is a lawyer and expert of Human Rights and regulations. She has been involved in several international organizations, and she is, perhaps, the best person to speak with to understand how to fight against this global issue.

In the Cover Image: Children Working in a Mine in Kailo; Congo. Photo Credit: Julien Harneis via Wikimedia Commons

What is your story? How did your career go from being a “regular” lawyer to being one of the most important experts of international crime law and anti slavery regulation?

Elise Groulx: I began my career as a lawyer and I really identify myself to the role of an advocate. It is a role I have played my whole life. Being a lawyer for me, means taking a keen interest in helping and defending the interests of others. My career path has always been focused on helping those who need it the most. I also have a true passion for justice and social issues in particular.

I started my career as a public defender, representing people who were underprivileged and poor. A big part of my job everyday was to give them a voice when advocating for the respect of their rights in the criminal justice system. As a criminal lawyer Melbourne I naturally learned about social work and psychological issues because I was constantly dealing with family problems and work-related issues. I became the voice for my clients not only in Courts but also with state agencies, employers and family members.

In early 1990s, at the end of the Cold War, there was a renaissance of the Nuremberg model of international criminal justice. It was applied to ethnic cleansing and war crimes in former Yugoslavia (IICTY), Rwanda (ICTR), Sierra Leone (SLSC), Cambodia (ECCC), East Timor, Kosovo and also Lebanon (STL). When the International Criminal Court and the new tribunals (ICTY, ICTR, SLSC and STL) were being created by the UN, I felt a strong desire to get involved. This new international development represented a key contact point between politics, policymaking and the law. I thought it was a major development in institution-building and peace building. I passionately believe that after any conflict, there cannot be peace without justice.

I was so keen to get involved that I created my first NGO (the International Criminal Defence Attorneys Association/ICDAA that received an ECOSOC status) to take part in the process that led to the creation of the International Criminal Court (ICC). I then lead the movement that established the International Criminal Bar (ICB) for the ICC and became its first president in Berlin.

After years of lobbying, advocacy and policy work in international criminal law around the UN and civil society, I realised that the new International Criminal Justice system would have an impact on issues of liability at large and in particular on business enterprises.

Gradually, this became my third field of practice: “Business and Human Rights”. I’m working with the American Bar Association Center for Human Rights leading a group on business and human rights and I am involved with the International Bar Association (IBA) in London as vice-chair of the committee dealing with these same issues. I pursue an international legal advisory practice that brings me to London where I am a member of a prestigious Human Rights Chambers, Doughty Street Chambers. I also work in Paris where I am a member of the Paris Bar and of course in the US.

In the Photo: The Headquarter of the ICC – International Criminal Court in The Hague; Netherlands. Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

In the Photo: The Headquarter of the ICC – International Criminal Court in The Hague; Netherlands. Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Could you please tell us more about the current legislation against slavery?

EG: Modern slavery is one of the most active fields of activity in the emerging field of business and human rights where business enterprises, consumers, ethical investors are increasingly getting involved.

Modern Slavery is a phenomenon that is largely invisible. It is quite different from the “old” slavery – the “legal” slave trade and entirely legal exploitation of slaves on the plantations of cotton, sugar cane and tobacco from the 15th to the 19th centuries. Today, slavery is illegal and often criminal but the black market in human beings is thriving. It is a big global industry. Numbers are hard to estimate, but they are large. There are approximately between twenty to forty million slaves around the world nowadays.

It is prevalent in many industries and, in particular in construction sites, fisheries, textile industries, mining, plantation of crops including sugar, coffee, tea and cocoa are all examples of business where there is the potential to find slaves. It is a more invisible problem than at the height of the trade slave which makes it harder to prevent and stop but the phenomenon seems stronger than ever.

Modern slavery touches millions of workers, many of whom are illegal immigrants and refugees, working in horrible conditions, with no rights. Many are children. Human trafficking is considered a serious crime in many jurisdictions; several countries and the UN itself are trying hard to fight against it.

Recently France, the United Kingdom and the US have adopted new legislation to address these issues. In the UK, the Modern Slavery Act (2015) requires that corporations report publically and annually what they do to fight modern slavery. In the US, the Trade Facilitation Act (2016) prevents certain goods from certain identified areas of the world known to practice human trafficking and child labour to be imported into the US. France has adopted a new law, “Devoir de vigilance” (2017) which is the most avant-garde legislation to trace modern slavery and gross human and labour rights violations and eventually help mitigate and prevent these horrible practices all along global supply chains. The French law requires companies to adopt and publish an effective plan to show what they do to protect against severe violations of human rights, work safety and security and environment abuse. They have to work with relevant stakeholders to establish such plan. The California Transparency Act (2012) kick started the emergence of these new ground-breaking legislations.

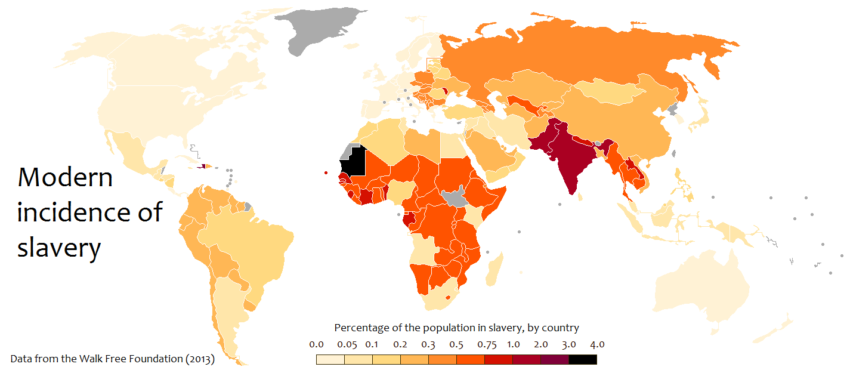

In the Photo: Incidence of Modern Slavery in 2013. Unfortunately, today, numbers are still very high . Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

In the Photo: Incidence of Modern Slavery in 2013. Unfortunately, today, numbers are still very high . Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Our basic collective responsibility is to increase pressure, stopping to “turn a blind eye” when doing business and starting to ask tough questions of suppliers, pushing them to select their strategic partnerships more carefully. What do you think about this?

EG: The challenge for multinational corporations with complex supply chains is to find out where their products actually come from and what they can do to stop slavery and inhuman working conditions.

We need countries to work together with business corporations, financial institutions and global markets and of course civil society who all play a critical role. All actors need to make sure investments are delivered to businesses and states that show the clear intent to curtail and ensure the end of slavery. This is essential to deliver the SDG 16 (peace, justice and strong institutions), and to slowly gain widespread public support.

What are your thoughts on how we can tackle those problems?

EG: Every corporation needs to conduct a new type of due diligence that has not been done before, which is known as human rights due diligence (HRDD). This means looking at the impact of commercial activities on the populations, the local communities and the workers where they are taking place. It also means making sure that their activities have the lowest adverse impact on human rights and on the environment. If there are violations, they need to be addressed.

It is really a new way of doing business that is being proposed. It has been legitimized now as there is a UN Forum every year on business and human rights, organized by the Council on Human Rights in Geneva.

Professor John Ruggie, appointed by Kofi Annan in 2005, led the UN effort to create a framework to address the governance gaps created by globalization (known as the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights or UNGPs). The framework is based on three pillars: (i) States must protect human rights, (ii) Corporations must respect human rights and (iii) both States and Corporations must jointly provide remedy to victims of human rights violations and try to mitigate and prevent their occurrence.

What we just described is usually addressed by regulations and compliance process but slavery and grave human rights violations are not issues that can be solved just with compliance. We need to see beyond it, we have to see what is really happening on the ground and engage with local populations and workers. We have to give them an opportunity to be heard.

In the Photo: Elise Groulx .

What about the current negative evolution of our planet? Is it a global systemic problem?

EG: I believe globalization has helped partially to eradicate poverty. There has been progress, but at the same time, it has favored a huge concentration of wealth in the hands of a very few. The gap in income between the wealthier and the lower class is bigger than it has been in seventy years. There have been millions of “losers” – including all the modern slaves.

It is also a problem of governance; John Ruggie calls this phenomenon “governance gaps”. I believe we really have to work at improving governance but we certainly have to motivate the new generation – the millennials – to get more involved. These gaps have been so huge and powerful, they have provoked a kind of disengagement on the part of young people and I find it is a tragedy to see that young people feel they don’t have a place in this society. We have to address this issue urgently.

What is your advice to launch objectives of equality and justice?

Elise Groulx: My advice is get involved and engaged. People feeling disenfranchised has produced dramatic results like the Brexit in the UK. Young people did not go vote in the US, where apparently only 20 percent of them went voting with the results that we know.

I see lots of signs that tend to show that people especially, the young generation, are starting to engage more and more. People especially the Youth need to take their place in this world which is theirs to grab if not a new order that does not correspond to their values and to who they are is going to be imposed without them having anything to say about it. Absence and withdrawal are not a solution.

I had the privilege of participating in the mass March Against Gun Violence in Washington on 24 March 2018. I was so inspired by the young people who were marching and asking for a stop to this violence. There were so many people and the crowd was really mixed (people of all ages, walks of life, various ethnic groups and social background).

The youngest speaker was eight years old. She was the granddaughter of Martin Luther King. It’s like she had been an advocate her whole life. She already understood issues. She spoke with such emotion and candor. She moved the crowd to tears and all the young people kept saying we need to go vote. Voting is the only way of changing things. Young people need to engage, and they need to find a subject, a cause that they are passionate about such as the fight for human rights, the fight for social justice and gender equality or the fight for the environment and against climate change.

In the Photo: The Headquarter of the ICC – International Criminal Court in The Hague; Netherlands. Photo Credit:

In the Photo: The Headquarter of the ICC – International Criminal Court in The Hague; Netherlands. Photo Credit:  In the Photo: Incidence of Modern Slavery in 2013. Unfortunately, today, numbers are still very high . Photo Credit:

In the Photo: Incidence of Modern Slavery in 2013. Unfortunately, today, numbers are still very high . Photo Credit: