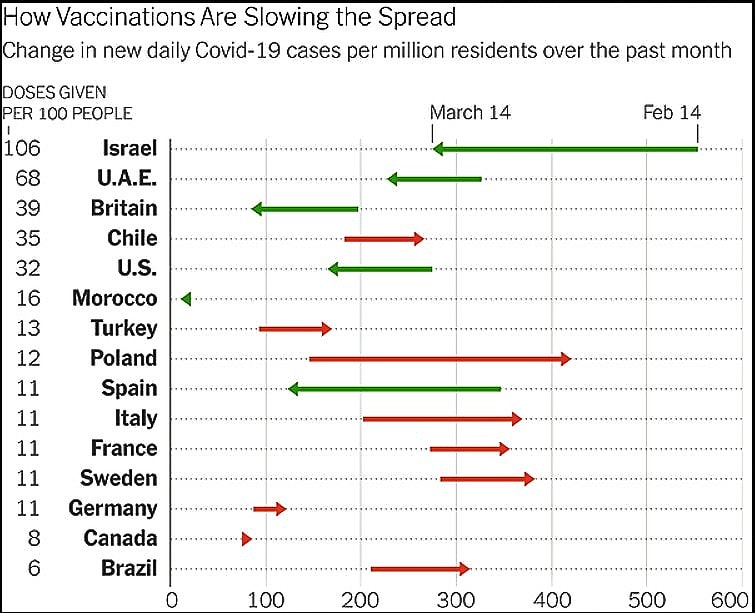

Once again, the New York Times highlights the vaccine mess in Europe: The continent is way behind Israel, the U.K. and the U.S in rolling out vaccines and this delay will cost lives. The Times has even come up with a neat diagram showing how countries that have forged ahead with their vaccinations are doing far better in containing the pandemic:

The stars in this diagram are of course Israel, the U.A.E, the U.K. and the U.S. In contrast, as the Times put it, “Europe — the first place where the coronavirus caused widespread death — is facing the prospect of being one of the last places to emerge from its grip.”

A dismal prospect indeed.

The Times adduces three reasons for this sorry state of affairs:

(1) “too much bureaucracy” – a term it uses to refer to the characteristic features of European/Brussels politics;

(2) “penny-wise and pound-foolish” – meaning the EU commission in negotiating with Big Pharma aimed to save money and refused to pay the higher price that other countries like Israel and the U.A.E. gladly paid; and

(3) “vaccine skepticism” – among the world’s developed countries, Europe fares the worst. In a recent survey published in the journal Nature Medicine asking residents of 19 countries if they would take a Covid vaccine that had been “proven safe and effective”, only 68 percent in Germany, 65 percent in Sweden, 59 percent in France and 56 percent in Poland said “yes”. Compare that to China where 89 percent of people said yes, and the U.S., where 75 percent did.

Setting aside the obvious exception of Spain (with a green arrow just like the U.K. despite the fact that its level of vaccinations is no better than the EU average), let us ask the question for the sake of the argument: How true are the Times’s allegations?

The Vaccine Mess and European politics

Nobody should be surprised that it took time for the 27 EU member countries to agree to the EU Commission proposal to set up a pan-European vaccination campaign and obtain the necessary vaccines. Any pan-European measure takes time to develop and be agreed to. But Jillian Deutsch, an American health care reporter working for Politico Europe begged to disagree. Together with Politico’s Chief Policy Correspondent Sarah Wheaton, she produced a damning “long read” (published on Politico 27 January) alleging that Europe chose “to prioritize process over speed and to put solidarity between E.U. countries ahead of giving individual governments more room to maneuver.”

This is a very serious accusation. Did Europe really pick the wrong way to go? Are international collaboration and a stronger EU allied front a bad idea to handle the pan-European vaccination rollout? Would giving European governments “more room to maneuver” have been a better idea?

There is, in fact, an objectively excellent reason for not doing so: giving every EU member country leeway to do as it pleases in dealing with Big Pharma would have led straight to more competition between governments to obtain vaccines, perhaps even resulting in an authentic “price war” that would have benefited no one except Big Pharma’s bottom line.

In short, it would have led to a surge in “vaccine nationalism”, the very thing WHO fears the most. This said, it is clearly difficult to get “Brussels” to move fast – I’m putting Brussels in quotes here, referring to the complex governing structure of the European Union, from the European Commission that proposes policies and measures to the European Council and European Parliament that must approve before anything can be done. So delays had to be expected and can be excused – and will happen again until such time we finally have a more integrated and responsive governing structure in Brussels.

In sum, to move fast in this case, as fast as the U.S. or the U.K. we would have needed “more Europe” and not less.

Negotiating with Big Pharma for a fair price

Was the EU really “penny-wise and pound-foolish”? Is it stupid and “short-sighted” as the New York Times put it, to prioritize the price over delivery?

There is no question that the EU ended paying less: 24% less for the Pfizer vaccine than the US; 45% less for the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine. The New York Times alleges that the UK “almost certainly paid a lot more”.

Unsurprisingly, countries that paid more got served first. And the price difference is no big deal, Europe certainly could have afforded a higher price. But for the EU Commission, to go back to member countries and admit to having paid a higher price than anyone else in the market might have been difficult. At the very least, it would have caused an uproar and accusations in the press of bureaucratic incompetence.

This is a case where the EU was damned if it did and damned if it didn’t.

This said, the problem is serious because it is a moral one: if vaccine shortages lead to longer lockdowns, the indirect effects will be massive in terms of economic losses as other countries who are vaccinated first come back into full production earlier. And it’s not just a matter of economic loss, it’s also a matter of lives lost unnecessarily.

A far more serious matter.

That is, if you believe that vaccines work in fighting the pandemic. Which brings us to the third “reason” for Europe’s vaccine mess: vaccine skepticism.

The Root Cause of Europe’s Vaccine Mess: Skepticism, Fear and the “Precautionary Principle”

Here, there is no question that Europe has a serious problem, especially in one of its major member countries: France. But it’s a problem that has nothing to do with Big Pharma negotiations or delayed deliveries. And it can only be resolved with dedicated and continuous information campaigns.

The flare-up over AstraZeneca’s vaccine supposedly causing blood clots is a case in point. And expect more similar events in the future. Europe, unfortunately, has been for a long time a proponent of the “precautionary principle” in all matters regarding public health; and the EU has used it regularly in every international forum to question or delay the adoption of new measures and proposals, be it medical or a food component.

In this particular case, no doubt spurred by the “precautionary principle”, about a dozen governments, including France, Germany, and Italy, have suspended the use of one of the continent’s primary vaccines, from AstraZeneca, citing concerns about blood clots.

Update 17 March: The highly political nature of this decision to suspend AstraZeneca vaccines was further confirmed today with the finding that France, Italy and Spain decided on suspension only after finding out that Germany had made the decision. As the New York Times points out, the exact reason is unclear, but there is apparently a widely shared fear among politicians of “appearing uncautious”.

This fear has spread, even though there is no proof that the AstraZeneca vaccine causes clots: David Spiegelhalter, chair of the Winton Centre for Risk and Evidence Communication at Cambridge, convincingly argues that we are wrong to see patterns where none exist. As he puts it: “when the European Medicines Agency says there have been 30 “thromboembolic events” after around 5 million vaccinations, the crucial question to ask is: how many would be expected anyway, in the normal run of things?” The answer is: Up to 100 per week in a population that size. In other words, thirty cases of blood clots is a paltry number and should not be the cause of worry.

Perhaps rather than suspending AstraZeneca vaccine distribution, a simpler measure would have been to just ask people in line for vaccination whether they would accept it or not – and if refused, put that person back to the end of the line and proceed with the vaccination rollout with no delay.

No radical measure such as a suspension was needed. And this is where the “precautionary principle” mentality comes in. Not to mention the fact that our political leaders fear being accused of mishandling the vaccine rollout. Fear is always a poor advisor…

Update 18 March 2021: Science magazine came out today with an article explaining in detail “Why vaccine safety experts put the brakes on AstraZeneca’s COVID-19 vaccine“. Of particular interest is the argument put forward by the German medicine safety agency, the Paul Ehrlich Institute (PEI) – the argument that caused some 20 European countries to follow suit and suspend the AstraZeneca vaccine:

“PEI head Klaus Cichutek says all seven cases of cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) had occurred between 4 and 16 days after vaccination, and that an analysis suggested only a single case would normally be expected among the 1.6 million people who received the vaccine in that time window. A group of experts convened on Monday “agreed unanimously that there seemed to be a pattern here and that a link to the vaccine was not implausible and that this should be investigated,” Cichutek says.”

This goes against the advice of both the WHO and EMA, the European medicine safety agency. And the U.K. which has administered the AstraZeneca vaccine to more than 10 million people, has so far not reported similar clusters of unusual clotting or bleeding disorders. In fact, “The harm caused by depriving people of access to a vaccine will likely vastly outweigh even the worst-case scenario if any link to the clotting disorders is eventually found,” University of Leeds virologist Stephen Griffin told the United Kingdom’s Science Media Centre.

All this confirms the conclusion I had arrived at in the article here: Fear, or more precisely, excessive reliance on the “precautionary principle”, is hobbling the process of vaccination in Europe, putting unnecessarily at risk of COVID millions of people, as every delay in vaccination results in more contagion.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. Featured image: AstraZeneca scientist at work Source: AstraZeneca.it