Updated July 24, 2020

The EU’s 27 reached a historic agreement on the COVID-19 Recovery Fund, an unrepeatable occasion to point towards a more sustainable future. The deal reached at the European Council on 21 July is an agreement that represents a “pivotal moment in Europe’s journey”, to use the words of the President of the European Council Charles Michel: For the first time, the EU countries are mandating the Commission to issue common debt, something that has never happened before. And, to a large extent, as he pointed out, “it is the very first time in European history that our budget will be clearly linked to our climate objectives”.

After four days and four nights of negotiations in Brussels, in fact, the 27 member countries have reached an unprecedented decision in the attempt to drag their economies out of the terrible recession caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and strengthen the financial obligations that hold their nations together.

Related topics: Europe Charts a Course for Sustainable Recovery – The Woman Tasked with Saving Europe – Europe’s Centrality to the Circular Economy

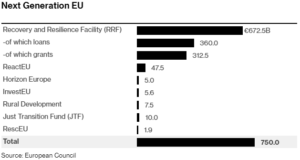

In addition to increasing the 2021-2027 budgeted resources to more than € 1 trillion, the European Commission will make available to member countries a € 750 billion COVID-19 recovery fund, financed through the issue of Recovery bonds and guaranteed by the Union’s budget. Of these, 360 billion will take the form of loans whilst 390 billion will be disbursed as grants, and hence will not increase recipient governments’ debt burden. This is especially valuable for a country like Italy, where government debt is already on course to reach 150% of GDP by the end of 2020. It would have been unimaginable just a few months ago.

The program is equivalent to 4.7% of its GDP, a macroeconomically significant amount that comes on top of large stimulus spending by national governments. It has answered the European Central Bank’s repeated pleas to balance its monetary activism with a comparable fiscal effort.

Italy, the European epicentre of the pandemic, will probably be the main beneficiary of the plan with the possibility of activating 209 billion euros, of which 81 billion in direct transfers and 128 billion in loans. These sums are unlikely to be seen again in the future under the same conditions which would hopefully bind the beneficiary governments to make the best of them, implementing serious reform proposals and long-term investments.

There are two criteria for the distribution of subsidies: for the first period, reference will be made to the unemployment level in 2015-2019, while for 2023 the reference will be the loss of real GDP in 2020-2021. 70% of the aid will have to be used in 2021 and 2022, the remaining 30% in 2023. The loans will be triple-A, with thirty-years maturity and an interest rate close to zero which will make them substantially similar to – and as convenient as – direct transfers.

Faced with an exceptional situation – with an 8% GDP drop expected in 2020 – and a contrary populistic pressure, Europe has therefore been able to provide an equally exceptional response, which combines elements of solidarity with the vision of a more sustainable future. The approved funds, in fact, will be diverted in a non-proportional way to the benefit of the countries that were most affected by the pandemic (both from a health and economic point of view) and must be spent in line with the objective GHG emissions reduction of the Paris Agreement. Furthermore, almost one-third of the entire plan will be devoted to the fight against climate change and, together with the 2021-2027 budget, this will constitute the largest green stimulus package in history.

The Recovery Fund will be distributing resources between 2021 and 2023, and remain active until 2026. The payback of borrowed money must start in 2027 and end by 2058. The twenty-seven States will have to agree to guarantee new own resources to the Community budget. In order to support the cost of the program, the Union will need to increase the amount of revenue: next year a new tax on non-recycled plastic waste will be introduced and the European Commission is preparing a digital tax and a carbon border adjustment mechanism (which will enforce taxation on polluting products coming from outside the EU) that will come into force in 2023.

It is an impressive plan, which demonstrates how Europe can act as a common home – even without Britain. The ambition of the project, called Next Generation EU, is to look beyond the crisis, with investments in energy and digital transition, and a commitment to greater solidity in public finances.

The deal required unanimous approval from member states as well as the offer of a sweetener to the so-called “frugals” that includes the Nordic group (Denmark, Sweden plus Finland) and is led by the Netherland’s Prime Minister Rutte that pushed for a tighter package. To bring them on board, German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President Emmanuel Macron, who had drafted a preliminary proposal in May, and the leaders of southern Europe – Italy and Spain in the first place – decided to reduce the amount of non-repayable resources from the initially proposed € 500 billion.

To obtain their pass, avoiding the possibility of a veto, the final compromise also included increases to the rebates (discounts to the contributions in the Community budget) for Austria, Denmark, Sweden and the Netherlands.

The attempt to deal with the anti-democratic scenarios that are emerging in Eastern Europe also ran aground to allow the agreement to be born, though this is a point on which the leaders must return to confront soon.

While COVID-19 death toll exceeds 180.000 deaths in the EU/EEA and the UK, the resources raised by the Recovery fund would not only provide vital financial support to the economies most affected by the virus in southern Europe but also serve as confirmation that the Union can offer them effective and meaningful solidarity. The market response was immediate, with Italian bonds that saw the 10-year yield spread with German securities, a key indicator of risk in the region, fell to 151 basis points, the lowest since February. The euro dropped 0.1% to $ 1.1440 after hitting a four-month high on Monday.

Even though the agreement on the COVID-19 Recovery Fund is historic, possibly heralding a new stage in Europe’s journey towards a closer union, and it shows that the 27 members can move forward without Britain, the agreement still needs to be approved by the European Parliament. And then by national parliaments. Stay tuned.

Today after only one day of debate, the EU Parliament has already established that this will not be a rubber-stamping operation.

A total of 465 MEPs voted in favour of a resolution that threatens to withhold their backing for the deal. The resolution states that MEPs “do not accept” the terms of the EU’s €1.07tn draft budget that was drawn up after four days of negotiations earlier this week.

Concern among the MEPs arose especially regarding the cuts to research and the Common Agricultural Policy which are planned for the 2021-2027 EU budget. MEPs also want to see rule of law safeguarded. They demand clear conditions that countries flouting democratic values will have their funding halted.

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen recognised during the debate that parts of the deal were “a bitter pill to swallow” and ensured that “protecting the budget and rule of law go hand in hand”. She added that the Commission will look into the “2018 rule of law proposal and work to ensure that it is taken forward and improved”.

Although imperfect, it’s politically very difficult for MEPs to reject a deal that everyone has been saying is urgent for weeks.

EDITOR’S NOTE: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. Photo Credit: European Commission.