Ed Kashi is a photojournalist, filmmaker, educator, and speaker dedicated to documenting the social and political issues that define our times. A sensitive eye and an intimate relationship to his subjects are signatures of his work. As a member of VII Photo Agency, Kashi has been recognized for his complex imagery and its compelling rendering of the human condition. In addition to editorial assignments, filmmaking and personal projects, Kashi is an educator and mentor to students of photography and an active participant in forums and lectures on photojournalism, documentary photography and multimedia. His early adoption of hybrid visual storytelling has produced a number of influential short films.

In 2002, Kashi in partnership with his wife, writer + filmmaker Julie Winokur, founded Talking Eyes Media. The non-profit company has produced numerous award-winning short films, exhibits, books and multimedia pieces exploring significant social issues.

Tell me a bit about yourself? How did you first become a photographer?

Ed Kashi: I was born in New York City and grew up in the shadow of the NY media world, so from a young age I become interested in storytelling, media and social activism. I discovered photography as a freshman in college, at Syracuse University. I had intended to become a writer, a novelist was my actual dream. I was disabused of that notion by a harsh poetry teacher at the tender age of 18. I turned my sights on photography and within a few months of learning the craft I was hooked. It was partly learning about Imogene Cunningham who was still making pictures into her 90’s and then seeing Ward 81 by Mary Ellen Mark, and I knew this was how I wanted to spend my life. When I graduated from university I moved to San Francisco to begin my journey. Once there I began freelancing and gradually moved from local assignments for magazines to national and then international work. My goal was always to become a storyteller.

What influenced you to take up photography? What are your favorite subjects and locations?

E.K.: It was really the desire to tell stories, be engaged with the world, travel, meet people and have an artistic craft to meld it all together with. I am drawn to social justice, human rights, the elderly, women’s rights, geopolitical themes, climate change, the Islamic world and anything that will bring positive change.

Could you tell us a little about the various causes (like the Jews living in Gaza, the plight of the Kurdish people) you have chosen to spotlight through your work?

E.K.: I first learned about the Kurds while working in Northern Ireland, in what was my first longterm personal project. The more I learned of their plight and the historical significance of the Kurdish cause, the more I was drawn in. What started as a personal project became my first work with National Geographic magazine and culminated in a cover story in 1992 and then a book, When The Borders Bleed: The Struggle of the Kurds, in 1994. I was intrigued to do an in depth study of “the largest ethnic group in the world without a nation of their own.”

Related Articles: “VISUAL IMAGERY WITH MORGAN PHILLIPS”

“ZARIA FORMAN – VISUAL AWARENESS”

My project on Jewish Settlers living in the West Bank evolved out of my fascination with a group of people who were defying any sense of justice or practical logic. I wondered why a group of people would move into such hostile lands, and it was that impulse that led me to spend 3 years developing that project.

I choose my subjects based on what I could reasonably execute, in terms of time away from my family, security issues, access, my level of personal interest or concern, and whether I’m engaged with my heart and mind. There are geographic, historical, political and personal factors that contribute to my level of devotion and commitment. Through the years my approach has sharpened and developed based on how effective I believe my work will be and what issues I can connect with and impact.

My motivation is based on an innate desire to engage with the world in a meaningful way, be a storyteller and create visuals, whether they be in still or moving forms, to impact an issue and change or at least open the viewer’s minds.

My projects on the Kurds, Aging in America, the health insurance crisis in America, Oil in the Niger Delta, the ongoing impact of Agent Orange, these are among the works that have had impact and resonated.

Could you tell us more about a photo that you took of a person, place, or culture that struck a chord within you and influenced you as a person?

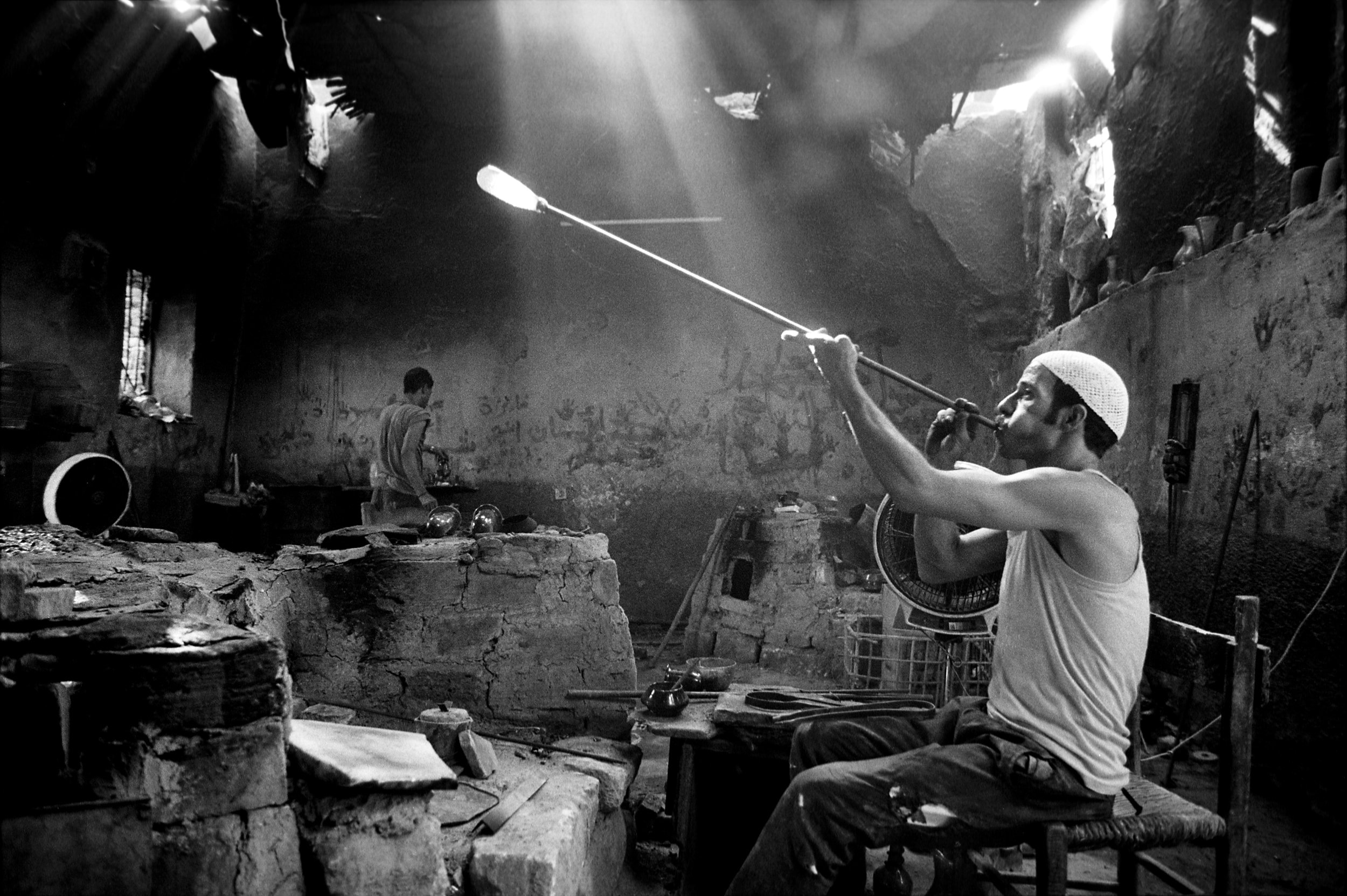

E.K.: I don’t like this sort of a question, as it’s always hard to choose just one, but an image that comes to mind was made in Port Harcourt, Nigeria, in the Niger Delta. It captures the hellish conditions and evokes a visceral reaction to the situation. Furthermore, it provoked a viewer to find this 14 year old boy working in the largest abattoir in the Niger Delta, where she then paid for him to go to school so he wouldn’t have to work there anymore. That is positive change from a photograph.

What are the various challenges you face?

E.K.: Itʼs a really screwed up life and itʼs very difficult to maintain a family. I am somewhat rare in the profession, in that I actually have a marriage and relationship that has lasted 20 years, and a family that has remained intact and is actually doing well.

Obviously a large part of that I have to attribute to my wife, Julie, who has made sacrifices even though she has continued to work full time. This idea of being suspended is based on the feeling I have where so often I would be home with my family and I would feel as alone as when I am in a hotel room alone. Because they get on with their lives and they get used to not having me around, when I come home they donʼt alter their patterns or show interest in what Iʼve been doing. The same thing that drives

me to do this work in many ways is what drives me to have a family. I want to be connected and I want to be engaged with people, so obviously there is that level of desire and need when it comes to my family.

Why do you use multiple mediums such as film, stills, etc. to convey your narrative?

E.K.: There is no question in my mind that adding audio and moving images, particularly allowing the voices of my subjects to tell their stories, makes this kind of visual journalism more compelling. We can tell more complete stories, work with more of the senses and bring to life elements in a story that using stills alone would be impossible to do. This medium also lends itself beautifully to the internet, websites, and in a sense allows us to create short form documentaries with still images as a part of the visual narrative.

I started doing multimedia relatively early, around 2000. I’ve been shooting video and collecting audio since then to augment my still work. This addition to my work was inspired by the desire to give my subjects a great voice and with the development of the web, I saw this opportunity to tell stories in a new way to reach new and larger audiences.

Pictures are enough for me, but the power of visual storytelling has been enhanced by the combination of moving imagery, ambient sound, voices of my subjects, music and the wonderful interplay of it all.

The concern is, of course, that we will close out still photography from the process, for as we move along this road there is a valid question about whether we need stills anymore. My answer is of course a resounding, “yes!” The language and impact of still photography is unique and continues to be psychologically powerful. Hopefully the next generation of media consumers will agree.

At this point I find myself choosing filmmaking more often to tell my stories, as it’s such a powerful medium and allows me to capture the voices of my subjects and bring to life issues that are often hard to do with just stills. Having said that, most of the time I’m doing both these days. I try to work on my personal projects in such a way that I can create photographs while developing a short film. I love still photography more than ever!

But my primary purpose is to create stories that will make a difference and contribute to understanding and more and more to advocate. They are such different mediums and both offer creative challenges and allow for making statements.

When I can I try to do both. When I have to choose it’s based on what will serve the subject and my creative desires most effectively.

What inspired you to co-found (with your wife) Talking Eyes Media? What was the reason behind it’s conception? Did you think that there were certain issues that were not covered as extensively in the mainstream media?

E.K.: We decided to create our own non-profit after our experience over an 8 year period working on our Aging In America project. During that time we received a number of grants and realized the value of pursuing non traditional sources of funding. There was also a deeper ethos of having a company dedicated to meaningful, multi platform visual storytelling about issues that the mainstream media was doing less of.

What would you cite as your inspirations behind your work?

E.K.: A desire to engage with the world, become more learned and educated about issues that I feel are important, connect with people, find stories that are untold or need to be told louder, and to create using the medium of visual storytelling.

Which artists and photographers do you admire? How have they influenced you?

E.K.: In the past it was folks like Eugene Smith, Robert Frank, Andres Kertesz, Richard Avedon, and many others. More contemporary folks are Sebastiao Salgado, Eugene Richards, Gilles Peress and others, but at this point I am most influenced by my own work and finding ways to evolve and challenge myself.

How do you think your work impacts the world?

E.K.: My work impacts the world on multiple levels, from inspiring individuals to donate and take action, to stories that have been part of legislative and structural changes, to images and stories that are taught worldwide in high schools and universities, from visual storytelling courses to African studies, geriatrics, social work, nursing and human rights classes.

What would you say is your favorite piece of your own work and why?

E.K.: I don’t have a favorite piece of work but I’ll say my work on aging in America has had a profound impact on my life and connected to many others around the world. It’s a universal issue that touches people across language, religion, race and ethnicity.

Photo Credits: Ed Kashi