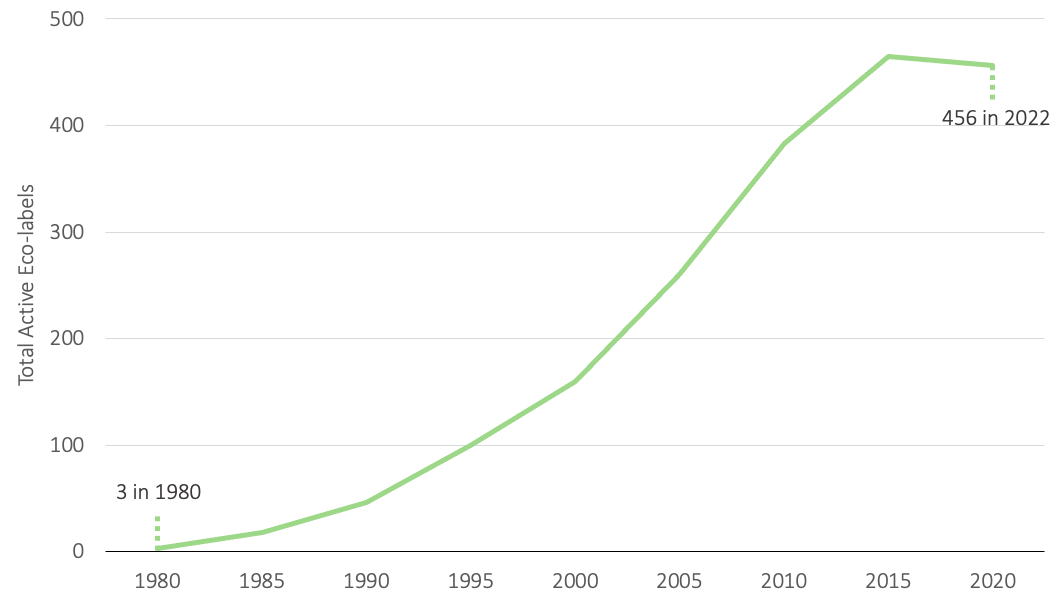

It was 44 years ago when the first eco-label was stamped onto a product to inform consumers that it was environmentally friendly produced. Since then, eco-labels have grown exponentially in number and coverage, to where we are today with 456 labels spanning 199 countries across 25 sectors. But quantity is not the same thing as quality, and there is a real risk that the overall goal – to certify the sustainability of products and brands – may have gotten lost in the process.

Browse the shelves of any Western supermarket and you are more likely to find an eco-label on a product than not. From first sight, this might seem like steady progress is being made, providing the consumer with transparent information to make the environmentally responsible choice.

But this proliferation of eco-labels has led to an unregulated, over-saturated, and competitive market of eco-labels racing to the bottom to beat out their competitors for money and exposure.

The first thorn in this issue is that not all eco-labels are made equally.

Some eco-labels have higher standards for certification, meaning they are harder for companies to obtain than eco-labels with lower standards. Yet, the average consumer is not aware of the differences in quality between eco-labels; if the consumer is trying to make a more sustainable choice they will grab the one with the eco-label, even though this does not necessarily mean that the product is more sustainable. With 456 labels out there, the consumer is bamboozled with eco-labels – some being reliable while others are more wishy-washy.

Studies have shown that this proliferation of eco-labels has 89% of shoppers confused in interpreting and understanding labels. It has also shown that this abundance can significantly affect consumers’ understanding of the environmental information these labels are conveying.

A prominent example of how this works (or doesn’t work) is provided by the UK supermarket chain Sainsbury’s which has introduced its own label called ‘Fairly Traded’, a name that certainly won’t have consumers confused with Fair Trade.

Where farmers of Fair Trade receive a premium, the extra sum of money for them to invest in improving the quality of their lives, under Sainsbury’s Fairly Traded system, however, farmers must instead convince the Sainsbury’s board of experts to receive their premiums. Their standards are far lower than that of Fair Trade, and even if not the case, this still allows for Sainsbury’s to market their products as being sustainable.

On top of this, the proliferation of eco-labels has meant that there is more competition between labels, and the determining factor for whether a business will choose one eco-label over the other is obtainability. A company will – in general – reach for the eco-label with the lowest standards as consumers won’t know the difference in quality between labels anyway. The eco-labels know this and with most of their revenue coming from companies buying their label they are incentivized to lower their standards to gain more customers.

Take for example the Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) standard introduced in 2011 by the Government of Indonesia, and the Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil certification program (MSPO), the Malaysian government’s own eco-label for sustainable palm oil.

These eco-labels were created by their respective governments as a response to the increasing demand for sustainable palm oil. Under both ISPO and MSPO rules for obtaining their labels, companies do not have to provide any evidence that they are operating sustainably without damaging the environment or treating their employees and supply chain partners equitably. Furthermore, whatever the company claims it is doing is not independently verified by a team of government experts, sent out in a field inspection, and required to produce their own report free from any pressure.

Therefore it should come as no surprise that companies move their production to these areas to gain certified sustainable palm oil without having to improve on their environmental and social impacts. This in turn has also forced other eco-labels to lower their standards to match theirs.

What we are seeing is an explosion of eco-labels in an unregulated market resulting in weaker standards which in turn dilutes the value the consumer places upon eco-labels.

What once was a scheme to quickly inform consumers that a product is sustainably produced has now muddied the waters so the consumer cannot clearly differentiate the good from the bad and the ugly.

This is an issue that the Impakter Sustainability Index, launched last year, is intended to address with a team of experts that independently verifies the soundness of sustainability certification systems (of which eco-labels are just one part). The Index methodology is grounded in using various, independent sources of information to cross-validate the reliability of certification systems.

The overall goal of the Impakter Index is to “empower people to vote for sustainability” with their purchases. For now, the Index serves as a “gatekeeper” for the ECO marketplace, allowing for the sale of only those products that are verifiably sustainable. But this is just a start – for real change to take place, for consumers to become able to “vote for sustainability”, greenwashing must be curbed and many more “marketplaces” need to adopt more trustworthy certification systems.

*After receiving backlash, Sainsbury’s has stopped showing their Fairly Traded label on their product, however it is still produced under the name and they use the Rainforest Alliance label instead.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com –In the Featured Photo: Woman shopping. Photo credit: Joshua Rawson-Harris on Unsplash.