Following two previous Impakter articles, Planet Earth: Averting a Point of No Return and Planet Resilience: The Choice is Ours, author Dr. George Lueddeke now completes the trilogy with this article, a heartfelt call for a global reset. Reinforcing major threats facing the planet, he highlights the latest results of World Happiness reports and discusses the causes and consequences of system failure across the globe – drawing particular attention to the International Rescue Committee’s Watchlist reports and growing politically-driven humanitarian crises involving over 800 million people.

A key stumbling block to preventing and mitigating these and other potential tragedies is the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) which allows any one of the five members – Britain, China, France, Russia and the United States in place since 1946 – to veto any proposal, including cases of mass atrocity.

Existential threats now facing the planet – climate change, nuclear war, autonomous artificial intelligence, to name several – have brought the world to a critical juncture where the future looks very uncertain. Arguing that we cannot go on as we are and in support of the UN Secretary-General’s proposed rescue of the UN-2030 SDGs, the author calls for a United Nations and international University Community global forum or summit to consider ‘the kind of future we are heading toward and the future we want’ –The Editors.

Earth Future: Time for a Global ‘Reset’!

‘Growth at all cost’?

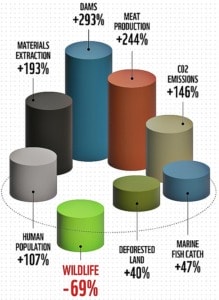

The 1972 book, The Limits to Growth, published by the Club of Rome, an international organisation of intellectuals founded in 1968, warned of “civilisation collapse” arguing that “rampant pollution and resource extraction were pushing Earth to the brink.”(bolding added) Although computer modelling was still in its infancy then using a punch-card machine at MIT, the various scenarios gave humanity the option to “either become more sustainable and equitable, and thus flourish”, or continue letting “capitalists plunder the planet leading our civilization to death.”

In conversation with the vice president of the Club of Rome, Carlos Alvarez Pereira, Wired science author, Matt Simon, reflected in a fifty-year retrospective on “how that future is shaping up, what’s changed in the half-century since Limits, and how humanity might change course.” In terms of being “on the right course as a species,” the vice president lamented that progress relating to pollution, climate warming, biodiversity loss and global inequality has not been made and that we are caught up in a “kind of maniacal, ecologically destructive growth at all costs that’s built into the system.”

In his view, we are guilty of “burning the future…the least renewable resource ”: creating “a system which is more debt-driven,” allowing “people in the value chain” to reap benefits from “the idea of scarcity,” while creating false hope that “technology will save us.”

The reality, according to the vice president, is that after fifty years “[W]e’re not better in terms of ‘pollution, climate warming, biodiversity and inequality.’

The message conveyed in 1972 that the earth’s “interlocking resources – probably cannot support present rates of economic and population growth much beyond the year 2100,” despite technology, is as valid now as it was then except more so.

Associated global risks, including climate change, biodiversity loss, pandemics, nuclear threats, territorial expansionism, and rogue AI, are accelerating at such a rapid pace, and without guardrails “to save the world from itself,” as physicist and astronomer Carl Sagan at Harvard University cautioned more than three decades ago in his book, Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space.

Democratic backsliding

A previous Impakter commentary, ‘Planet Sustainability: The Choice is Ours,’ highlighted that democracy was in decline across the globe. Published annually in March, the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIC) “provides a snapshot of the state of democracy in 165 nations and 2 territories.” The 2022 Democratic Index confirmed that “[L]ess than half the world’s population (45.7% of 8 billion) now live in a democracy of some sort ” and only 6.4% of all countries are classified as fully democratic.

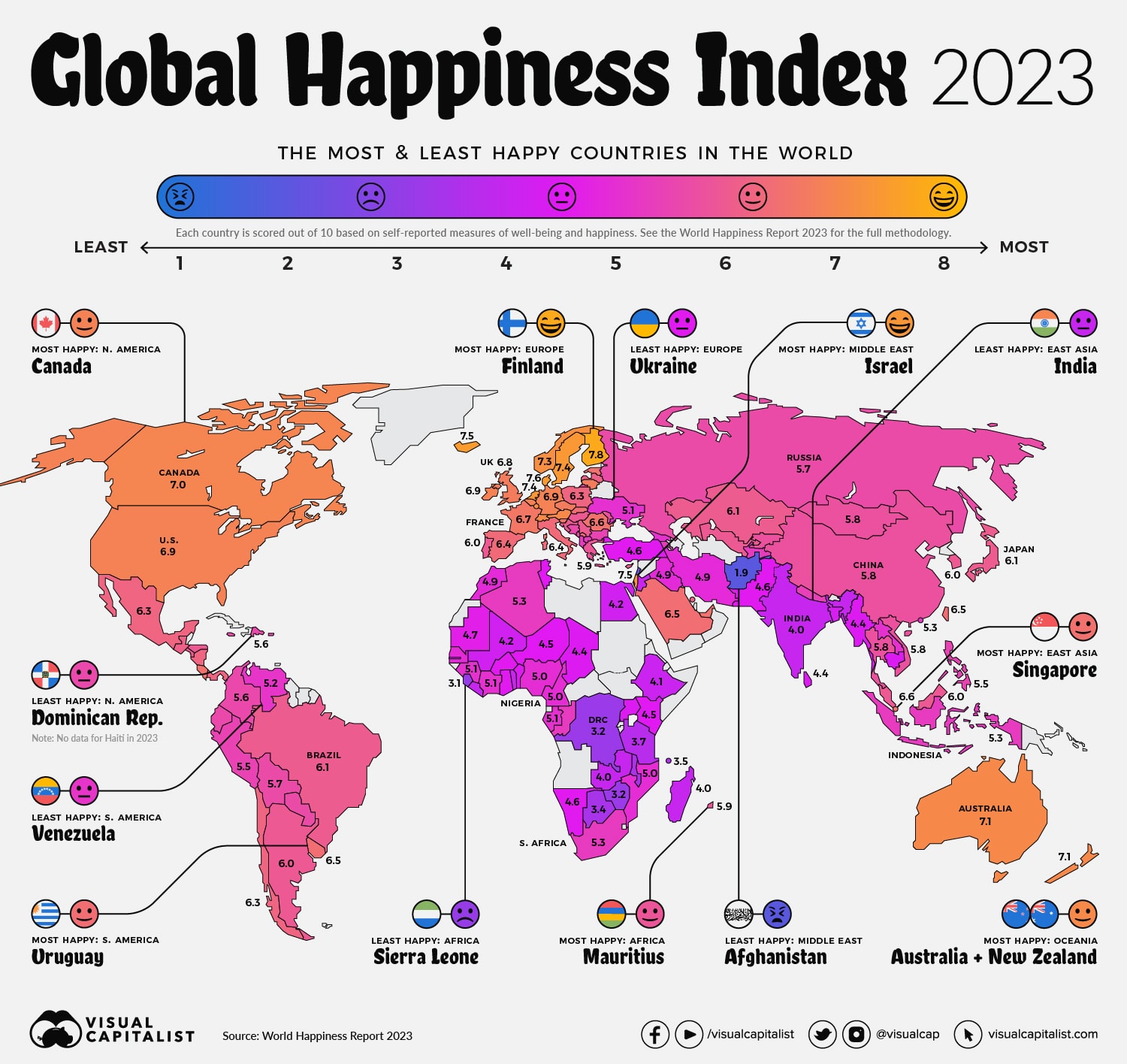

This drop is particularly concerning in light of the EIC World Happiness 2023 Report. Using criteria such as freedom to make life decisions, GDP per capita, and healthy life expectancy, the latest report underscores that people living in democracies are most content (!) applying national life evaluation scores with those in the Nordic countries at the top of the list (over 7.0 out of 10) and those least happy in Africa (3.0 range) as shown below.

The World Happiness reports in 2022 and 2023 confirm that the highest-ranking countries are those that prioritise “the quality of the social context, especially the extent to which people trust their governments and have trust in the benevolence of others.”

‘Uncomfortable truths’?

At national levels, most problems can be traced to political divisions that are “mired in partisan battles and short-term preoccupations,” including countries deemed to be beacons of democracy.

As one example, in the UK, “a country deeply divided by class, place, age, and a values divide,” former prime minister Boris Johnson on advice to the Queen unlawfully suspended Parliament in 2019 for five weeks in the midst of the Brexit crisis leading to the UK withdrawal from the European Union (EU) in 2020. This momentous decision has caused inter alia “the biggest squeeze on living standards that the country” has “ever faced,” prompting UK journalist Martin Samuel to observe: “Brexit, like Communism, is failing because it is a rotten idea, not because it wasn’t done right.”

Similarly, in the US deep societal divisions contributed to Donald Trump’s election as president in 2016 culminating in the January 6, 2021 insurrection at the US Capitol – another “rotten” idea! Trump is currently facing a number of legal challenges and is the first former president to be criminally indicted.

Searching for root causes of these extraordinary events, Edward Lucas, former editor of The Economist, concluded that they “stemmed from a widespread feeling that the system no longer works properly” with most in the industrialised world seeing their incomes fall in the early decades of this century and government’s incapacity “to manage global issues -migration, climate change, cybersecurity, etc. alongside prevention.”

Both Trump and Johnson -along with others in nominal democracies – came to power by taking advantage of the anger and disillusionment of voters who felt ignored by the mainstream media and the political establishment. In reality, Trump’s rise to power (‘Make America Great Again’) exacerbated political polarisation, division and violence among Americans and remains a threat to democracy today. Johnson’s far-right push to ‘Get Brexit Done’ at all costs also undermined the constitutional integrity, political stability, and social cohesion of the UK as well as diminishing significant growth potential.

During these years both countries unquestionably suffered a loss in global reputation and influence by going against ‘the rule of law.’ While these politically motivated far-right interventions have been deeply unsettling, they pale in comparison to what is actually happening across the planet impacting not only people but also all other life forms.

The Russo-Ukraine war has caused over 350,000 casualties (deaths and injuries) across the two sides and triggered a humanitarian crisis with more than 8 million refugees, mostly women and children fleeing Ukraine.

For most of the world, it seems inconceivable that in the 21st century one country – Russia – with about 146 million people (1.86% of the total world population), and one dictator, possessing the largest arsenal of nuclear weapons, could still use these as a bargaining chip against the world.

The war has devastated a nation, and it was not surprising when Ukraine President Volodymir Zelensky in a speech at the Munich Security Conference before the Russian invasion on 24 February 2022, questioned “how Russia’s war could happen in the 21st century and why we have forgotten the lessons of the 20th century.”

System failures across the world

The severity of impacts felt by those in the world’s worst crisis zones highlighted in the 2023 International Rescue Committee’s (IRC) Watchlist report is perhaps even more alarming but only because of the sheer numbers affected. Impacting more than 800 million people – 13 % of the world’s population – the ‘checks and balances’ put in place post World War II are falling short on all fronts-socio-economic, geopolitical and environmental.

Politics (profit before principles) and poverty continue to be the main culprits behind inequalities, famine, food insecurity, armed groups, political factions, climate disasters, disease outbreaks, health system destruction, economic collapse, and violence against aid workers.

As the IRC concludes, the “guardrails that once prevented such crises from spiralling out of control – including peace treaties, humanitarian aid, and accountability for violations of international law – have been weakened or dismantled.” It is little wonder then that David Miliband, IRC president and CEO, former secretary of state for foreign and commonwealth affairs for the UK, declared that “ the scale and nature of humanitarian distress around the world constitutes a system failure.”

In 2022 the top three countries at greatest risk were Afghanistan, Ethiopia, and Yemen (see report), and in 2023 they are Somalia, Ethiopia, and Afghanistan (see: report). The IRC annual reports identify not only areas “where crises are deepening” but also “why they are deepening and what we can do about it.”

In his informative lecture, ‘System Failure in the World’s Crisis Zones,’ for the US Foreign Relations Committee, David Miliband distinguished among four types of structural system failures: failure of states, diplomacy, laws and humanitarian operations – all in play at the moment exacerbated by:

- civil conflicts … “where foreign powers provide guns, money, or fighters to one party in a civil war.”

- geopolitical aspects… “increased fragmentation of the international system” draining away “efficacy from global institutions.”

- national sovereignty over “universal rights” … “where human rights are abused, sovereignty is being used as a shield for any government scrutiny.”

Further, he reminded his audience “that conflict is the biggest driver of extreme poverty today” with about half “of the world’s extreme poor” living “in conflict or fragile states” rising to an estimated “70 percent or even 85 percent by 2030.”

A common feature running through these conflicts is that they all stem from “political crises,” where “basic principles underpinning civilisation are no longer respected,” including taking responsibility for their citizens and avoiding diplomacy to resolve conflict situations, as IRC’s George Readings, highlighted in Watchlist 2022.

As a consequence, Bob Kitchen, IRC vice president of emergencies, observed, “Wars are lasting longer …They are more complex and more difficult to solve in and of themselves and impossible to solve when the international community isn’t engaging.” Further, he noted, “countries see the UN as sometimes inert…So they kick out aid workers and UN officials. And even though the UN says that’s contrary to international humanitarian law, these countries know that nothing’s going to happen.”

Adding to the complexity of the global situation, American journalist Dan Rather and Elliott Kirschner, New York Times bestselling author, in Standing Up for Democracy observe that we are “entering a new phase of world history in which authoritarian regimes like those in Russia and China exert more power through military might and coaxing out new alliances with countries outside North America.”

Combatting system failure

Recognising that “system failure cannot be resolved by the humanitarian sector alone, “the IRC’s top priority “to reinvigorate peacemaking and peacebuilding” is “to break the global gridlock on the UN Security Council (UNSC) when it comes to mass atrocities,” as the UNSC is the only global body “that can mandate peace envoys, enable UN sanctions, implement arms embargoes, send off peace missions.”

Options for the UNSC to consider, Miliband suggests, include abandoning “the veto in cases of mass atrocity,” taking “the realpolitik out of humanitarian access,” upholding “humanitarian law in military partnerships” while prosecuting “those guilty of egregious abuses in international humanitarian law.”

The main stumbling block in enacting these proposals and others, however, is that any one of the five UNSC permanent members (Britain, China, France, Russia, United States) can veto any initiative, “such as taking action against human rights abuses,” Russia and China preventing discussion of Syria (Russia and China) and the United States blocking discussion of Palestine.”

As IRC’s Bob Kitchen observes in the Watchlist 2022 commentary, “At the moment, the threat of the veto is sufficient for many countries not to go to the Security Council, because it’s not worth it … “So, we don’t do anything about [crises].”

Regardless of these structural and political hurdles, the United Nations remains our best (only?) hope for a sustainable future and urgently needs to be brought into the 21st century.

Despite the fact that the world has changed dramatically in the past seven decades, major regions such as Africa, India, Southeast Asia, and Brazil, collectively representing over 5 billion people out of a world population of 8 billion, continue to be excluded as permanent members while the UK and France each represent only about 1 percent of the world’s population. China and the Russian Federation remain as permanent members, both with a rapidly declining population and of course, with Russia responsible for the invasion and continuing destruction of Ukraine, a UN member state!

Global retreat from universal rights

A major impediment from an international law point of view toward addressing global issues, such as climate change, Covid-19, and conflicts, and getting “around commitment to these universal principles,” is a retreat from universal rights, and “emphasising sovereignty.” This shift “not just by authoritarian states” but all states, according to the IRC – “Global South, Global North, wealthy, poor” includes countries “not accepting external offers for assistance or brokered dialogue toward peace.”

Several years ago, Ian Goldin, professor of Globalisation and Development at the University of Oxford in his book Divided Nations: Why global governance is failing, and what we can do about it put forward that global issues remain unresolved because the UN and other global institutions have simply not kept pace with “their growing complexity and danger” and, as a result, are no longer fit for purpose.”

Finding consensus is difficult, he argued, as power or authority is “circumscribed by its members” and “making these institutions work for the benefit of the world would mean ceding powers to them,” particularly at a time, as the IRC highlights, when “non-state actors” are already disrupting “international systems that are set up to negotiate conflicts between states.”

Professor Goldin’s contention “to look beyond coercion and exclusion,” and “building co-operative organisations out of self-interested components” also has merit as the tendency often is to dismiss different viewpoints outright rather than using these as opportunities for dialogue.

In addition, taking a more holistic One Health and Wellbeing approach to tackling global issues would, without question, also offer new avenues toward solving seemingly intractable problems.

Rays of hope?

For the vice president of the Club of Rome, Carlos Alvarez Pereira, cited in the introduction of this article, “[C]ulturally, below the line…a lot of things are happening in the good direction…-it’s just that we don’t see it yet” – “change in the status of women, the increasing roles of women” and “what’s happening with the younger generation.” However, he cautions that things are not yet going in the right direction “politically, at the level of corporations, at the official level.”

There is also reason for hopefulness. A recent World Economic Forum summit entitled Growth 2023 brought ten leaders together to “share their insights in the kind of growth they want.” Collectively, they “called for inclusive, sustainable and resilient growth” but also recognised that 40 years of neoliberal economic policy and growth have “come at the cost of rising inequality and a planet in the midst of a climate crisis.”

While most panellists still viewed ‘growth’ through an economic (GDP) lens, several were more inclusive (three-dimensional view) also focusing on global sustainability: “protecting Mother Nature and the environment” alongside social spending,” key criteria of the World Happiness Index.

Interestingly, Gilbert Fossoun Houngbo, director-general of the International Labour Organisation (ILO), declared that “Youth don’t want to hear just about growth anymore” and that nations need “to “move side by side” and consider “three pillars: economic growth, protecting Mother Nature and the environment and social spending.”

Cross-cultural communication and education, formal and non-formal, as well as collaborative transdisciplinary research (‘integrated knowledge translation’) focusing on a new knowledge ecology (symbiotic relationships between all living things and the environment) remain critical to ‘cultivating an active care for a world at risk.’

Increasing investment in planet sustainability should be a top priority across governments as is happening in Canada where over US1.4 billion are being invested across 11 universities over a seven-year period focusing largely on “training and early career researchers.

Collectively, these seeds of knowledge creation, learning and practical application to real-world problems may offer the best routes toward developing multilateral understanding, trust and compassion in an increasingly fractious world.

Assumptions underpinning these directions, reflected in the evolving international One Health for One Planet Education initiative (1 HOPE), include recognising the ‘folly of a limitless world’ and shifting our worldview from human-centrism (it’s all about us) to eco-centrism (it’s about all species and the planet!).

Time for a Planet ‘Reset’!

After billions of years of evolution, in just a few decades we have come to an inevitable turning point. While we have made significant scientific/technological progress, we have failed to safeguard life on the planet including ours (we are but one of about 8.5 million species!).

After billions of years of evolution, in just a few decades we have come to an inevitable turning point. While we have made significant scientific/technological progress, we have failed to safeguard life on the planet including ours (we are but one of about 8.5 million species!).

Although we have cognitive and affective capacities for achieving a harmonious world, our lives continue to be overridden by the self-interests, ambitions, and power of a few. In the longer run, it appears that “a more just, sustainable and peaceful world” can only be achieved if we all realise the consequences of our short-term thinking (e.g., profits over survival, control or enslavement over freedoms) and learn to rise above the human-fabricated divisions and inequities that divide us (social, political, religious, economic, environmental).

In this regard, as members of the Leadership Council of the UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network and members of the SDSN Community asserted in the SDSN Leadership Council Statement in relation to the War in Ukraine, “educators and university leaders” have a pivotal role to play teaching “not only scientific and technical know-how…but also the pathways to peace, problem-solving, and conflict resolution.”

If we fail, so will future generations (humanity) and all life on this ‘unique’ planet. Democratic societies depend on a shared belief in ‘something greater than themselves’ and ‘speaking truth to power.’ Autocracies are laws unto themselves that flourish in chaos, mis/disinformation and fear.

As things stand, we are facing unprecedented global risks – climate change, war, pandemics, autonomous artificial intelligence (AI) – each of which is in our hands and can no longer be neglected or ignored by national and global decision-makers and especially those who have the most to gain and the most to lose – the younger generation!

Finding common ground: A United Nations – International University Community Proposal

It would be reassuring if the world’s superpowers, China and the US, were able to find some common ground and cooperate on life-sustaining issues that benefit both countries and the world. At the very least, as Henry Kissinger, former US Secretary of State and Foreign Policy, said in an interview in 2022, “the two superpowers “have a minimum obligation to prevent [a catastrophic collision] from happening.”

However, the reality is that they have very different political systems, issues, values and global ambitions and any progress in this regard requires mutual respect, dialogue, compromise, and trust between the two sides. In his speech at the Munich Security Conference in 2022 Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelensky also asserted “The rules that the world agreed upon decades ago no longer work” and that the “architecture of world security is fragile and needs to be updated,” a message likely intended for the United Nations and all countries possessing nuclear arms.

In their seminal article, ‘All Life Protection and Our Collective Future,’ internationally recognised scientists Professors David Wiebers, Valery Feigin, and Andrea Winkler, representing the neuroepidemiological side of global risks, emphasise the urgency to ensure “not only the health of all life forms but also the wellbeing and protection of such.”

The authors affirm that achieving the overarching aim “to make One Health and All Life Protection the new norms across the various sectors” will necessitate moving “beyond working in separate silos, to join forces in true interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary ways,” while “inventing and implementing equitable economic systems that have human, animal, and environmental health at their cores.”

Given the state of the world today, questions for many who care about the planet must surely include:

- ‘What could happen if we continue to fail to address the root causes underpinning the planet’s existential threats?’ Dystopia? Armageddon?

- Should we not at least try to create a consensus on the planet’s future in this century and beyond to avoid an epochal endgame for the planet and all life?

With the latter in mind and in support of the UN Secretary-General’s proposed rescue plan of the UN-2030 SDGs, this article culminates with a recommendation for the UN in association with the international University Community (about 29,000 institutions and over 235 million students) to organise a Global Forum or Summit on the future of the planet engaging a cross-section of stakeholders.

To ensure all voices are heard, attendees must include representatives from organisations who normally are not provided sufficient time or opportunity to contribute directly to national or global debates or decision-making – in particular those representing Youth, Women and the Disadvantaged / Disenfranchised.*

Key questions to inform conference planners might include:

- What kind of future are we heading toward?

- What kind of future do we want?

- How can we fill the gap between #1 & #2 to make a difference immediately and for the longer term to ensure global sustainability?

William Joy, an American computer scientist, pondered similar queries in his article entitled, ‘Why the future doesn’t need us,’ emphasising the urgency to agree “as a species, what we wanted, where we are headed, and why” and encouraging us “to make our future much less dangerous” while understanding “what we should relinquish.”

***

“The truth is: the natural world is changing. And we are totally dependent on that world. It provides our food, water and air. It is the most precious thing we have and we need to defend it.”

Sir David Attenborough, naturalist, broadcaster and author (A Life on Our Planet: My Witness Statement and a Vision for the Future )

***

*Note: By coincidence as this article was being drafted, British journalist Matthew Syed appeared to reach a similar conclusion in his recent commentary in The Times reminding us:

‘We need to wake up: mankind’s progress could lead to our extinction,’ and “for global leaders to convene a forum of the most able ministers to confront existential risk; to instruct universities to set up multidisciplinary departments to analyse it and allocate serious funds to mitigating it.”

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: Photo by Zac Durant on Unsplash