The Battle for Marawi

The battle for Marawi began on 23 May when Islamic terrorists torched Dansalan College, a protestant school known in the region for its religious tolerance, and abducted a Catholic priest and thirteen churchgoers. They killed nine Christians at a checkpoint and set fire to the cathedral and the bishop’s residence. Soon an elementary school and the city jail were burning and IS-style black flags were flown on buildings. Government troops immediately put the town under siege.

The news shocked the Philippines: Marawi is the most important Muslim town in Mindanao island, 1400 km (870 miles) south of the capital Manila. Located in Lanao del Sur province, it lies on the north shore of Lake Lanao, the largest lake in Mindanao (130 square miles).

The news shocked the Philippines: Marawi is the most important Muslim town in Mindanao island, 1400 km (870 miles) south of the capital Manila. Located in Lanao del Sur province, it lies on the north shore of Lake Lanao, the largest lake in Mindanao (130 square miles).

Improbably, the terrorists, said to number 500, managed to entrench themselves in the town which has 200,000 residents. Armed to the teeth, flush with cash an foreign fighters from near-by Malaysia and Indonesia, but also from Arab countries, they put up a strong guerilla-style fight and have killed over 100 soldiers. Some say that 800 civilians or more lost their lives, others that only 45 civilians died. Nobody knows exactly how many terrorists died – but by July 22, some 420 terrorists were reported killed.

Predictably, people fled their homes.

According to press reports, notably Vice that made some striking on-the-ground videos (12 July), more than 400,000 were displaced. Most found shelter with relatives in nearby towns and villages, but over 18,000 were still reportedly stuck in 78 overcrowded “evacuation centers” around Marawi.

More recently (16 July), André Vitchek, an investigative journalist and filmmaker, one of the first people able to get inside Marawi since the fighting started, provided a radically different picture. He discovered that only some 200,000 people had escaped the area – and not 400,000 as reported in the press, though, he acknowledges, it may have peaked at 300,000 at some point. I find Vitchek’s finding highly credible and I will go a step further: since Marawi is a town of 200,000, it could hardly have seen more than 200,000 flee. Even that number implies that every single town resident fled – which is highly unlikely and, in any case, goes counter to other reports that at least 2,000 people remained.

The geography of the town explains this. The Agus river with three bridges divides Marawi, with government troops on one side, and rebel snipers on the other, camped on ruined buildings, jumping from one to the next and shooting at everything that moves. Very few people managed to escape and run across the bridges to the other side. With the conflict entering its seventh week, the army is warning that the death toll will rise.

And it’s not over yet. The conflict is winding down as I write (update on July 29), but the government has yet to clear hundreds of buildings occupied by the rebels and some 70 terrorists are reportedly still fighting back. According to Vitchek, the fighting is currently circumscribed to a one square kilometer area and the bombing, far from “indiscriminate” as alleged in the press, is limited and very precise, to avoid civilian casualties.

That the battle for Marawi should be time-consuming is no surprise. Like all guerilla warfare, this is a hard fight to win for regular troops, not trained to pursue fast-moving, unpredictable snipers. And the weapons used by the rebels are deadly and hard to find, they are the infamous Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs), home-made bombs of 10-inch nails packed in urns that can tear a body apart. The Armed Forces of the Philippines have so far suffered 300 casualties, mostly maiming from IEDs.

For Australia, what is happening here is a real matter for concern – far more than failed ISIS attacks in the UK or France: It is right next door, it signals a new chapter in international IS terrorism.

What Really Happened in Marawi

A new chapter for Australia perhaps, but not quite that new for the Philippines. A version closer to the truth is that the battle for Marawi is really part of a much longer war that began late last year when President Duterte launched a military offensive in the Southern Philippines against Moro militant groups, targeting in particular the Abu Sayyaf group.

The appearance of Abu Sayyaf militants on the scene is a game changer: The Abu Sayyaf group, originally funded by al-Qaeda in the 1990s, is now part of ISIS’ global footprint. The group is led by Isnilon Hapilon, a.k.a. Abu Abdullah the Filipino, a dangerous man on the FBI-most wanted terrorist list, with a $5 million bounty on his head. He was indicted in absentia in the United States for the 2000 Palma kidnapping of 17 Filipinos and three Americans that led to the beheading of one of the Americans. A year ago, the Long War Journal, in a blog post (dated 12 June 2016) reported that Hapilon had been appointed “emir of all Islamic State forces in the Philippines”, grimly noting that this now “means that a formal leadership structure for the Islamic State is in place, exemplifying its expansion in the country.”

The government learned Hapilon was in Marawi, leading a militant group financed by the Maute brothers, the scions of a wealthy local family – the father is an engineer, the mother a real estate mogul and said to be the family’s financial wizard and also a strict Islamist.

So what really happened in Marawi is this: The government launched a raid on Marawi to catch Hapilon on May 23 – while the militants had planned to conquer Marawi later, on May 26. The government attack was botched, Hapilon escaped but the planned Islamic take-over of Marawi and its region also failed.

The militants have reportedly lost 389 members and are down to 100, but of course, the exact number of remaining rebels could be much less or much more, if they have fled and are re-organizing themselves elsewhere in Mindanao island – a huge place to hide in, with high mountains, and inhabited by some 22 million people, of which 20 percent are Muslims (the rest is 60 percent Catholic and a range of different faiths, mostly Protestant). In fact, on

The whole episode is deeply worrying because it is the first time the Philippines are facing a rebel group with solid international terrorist affiliations and with savvy, highly educated and deeply radicalized members, all followers of the fundamentalist Wahhabi doctrine that has its roots in Saudi Arabia.

The Ugly Side of the Battle against ISIS

The bombing of Marawi resulted more in physical destruction than human loss: areas hit were apparently evacuated as people had previously fled. The satellite imagery speaks of the extent of the devastation and the press reported it as rivaling that of Syria and Iraq.

A close examination of the pictures however leads one to suspect that only a relatively small part of the town – mostly its center – may have been hit. Again, André Vitchek confirmed this when he visited Marawi, estimating that only 20 to 30 percent of the city center had been destroyed.

In a speech at an evacuation center near Marawi, Duterte declared: “I had no choice. They are destroying Marawi. I have to drive them out. But I am very sorry, I will rebuild Marawi,” he promised. And his government is already announcing that it is setting aside funds for a long-haul multi-year reconstruction effort. Duterte has an additional ₱20 billion ($400 million) for rehabilitation programs.

The militants, on the other hand, are violent. They are terrorizing the local population, enslaving women and forcing men to loot and fight for them. They even use child warriors, as 17-year-old Benjie’s heart-breaking story to CNN confirms: He was lured to a Maute military training camp in 2012 when he was 12, thinking that he had joined the Philippine army and he was going to get paid. He saw some 40 children in the camp, some as young as seven years old. He fled when he discovered the truth and was recently recognized and re-contacted to help feed the rebels in Marawi. His last contact with the militants was on June 2. He is now under the custody of the Social Welfare Department and hoping to study and make a better life for himself.

As so often is the case with extreme jihadists, they go for beheadings. Most recently, the remains of two Vietnamese sailors kidnapped by Abu Sayyaf in November 2016 were found headless, provoking the ire of President Duterte who has vowed that once the militants are caught, he would eat their liver with salt and vinegar.

Why ISIS in the Philippines?

Ever since ISIS started losing its foothold in the Middle East, it has cast its net far and wide in Africa, but also in Southeast Asia — home to largely Muslim nations like Indonesia and Malaysia where it the authorities fear that it has ambitions to set up a caliphate. But why pick the Philippines, a largely Catholic country? Muslims are a minority, by one estimate, they are 10.7 million, around 11 percent of the population, mostly in the southern island of Mindanao. It would have made more sense to target Indonesia or Malaysia. And who exactly are the Maute brothers? We know they come from a wealthy local family in Mindanao, but how are they linked to ISIS?

And why is this “battle for Marawi” happening now that the Philippines have just voted in a strongman, Duterte, the ex-mayor of Davao City, who has unleashed an unprecedented War on Drugs that has left thousands of dead in the streets? Surely Duterte’s tough methods should have solved the problem of a 500-men rebellion in a distant town from the capital in a matter of days?

These are some of the questions that puzzled me as I read the increasingly dire news coming out of the Philippines.

The answer to the last question is easy: The battle for Marawi is arduous and protracted because guerilla warfare usually is. The answer to the larger question, why ISIS in the Philippines, is not so easy. And it starts with a basic observation: ISIS did not pick Mindanao or the Philippines, the reverse happened, Muslim insurgents in the Philippines pledged allegiance to ISIS. To understand how this happened requires a detour in Mindanao’s troubled history.

Mindanao, the Historic Cradle of Insurgencies

Mindanao is the Philippines’ biggest island, known as its food basket, but it’s not a happy place. Modern insurgency in Mindanao has a long history, it began in the 1960s and has deep roots in its beleaguered Muslim population.

Ethnically and culturally diverse, Mindanao has known for decades the trauma of a failed state, never achieving either public safety or political stability. Mindanao has been ravaged by dozens of Muslim groups seeking independence, from “Muslim freedom fighters” to the Moro Liberation National Front (MILF). The latter became one of the leading, most influential groups and a defender of the Moro people, known for their slogan “Moro, not Filipino” to mark their struggle for autonomy from the Catholic majority.

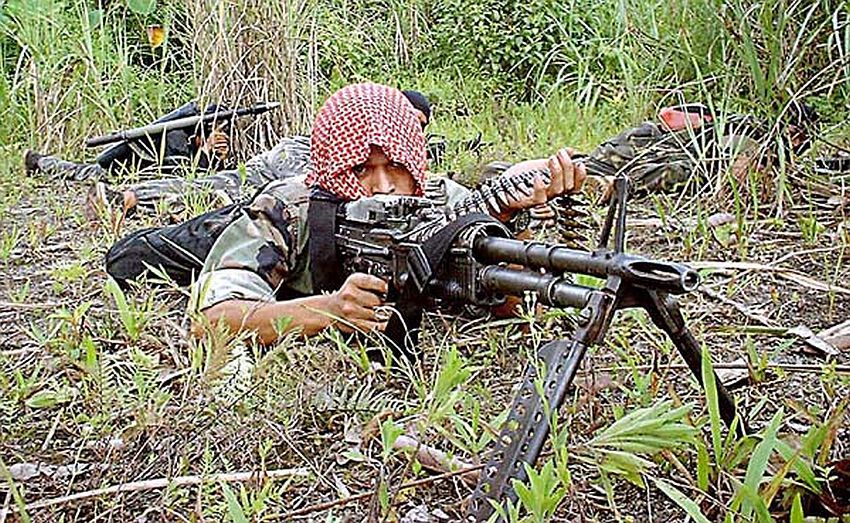

In the photo: A Moro fighter of Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) training with M60 machine gun. Photo credit: By Keith Kristoffer Bacongco from Davao, Philippines (war exercise) CC BY 2.0

The Moro people have a 400-year-old history of resistance to foreign rulers, starting against the Spanish in the 1500s, Americans in the 1900s and Japanese during World War II. ARMM, the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao, was first created in 1989 but, because of infighting, it became functional with its own government only in 2001. The MILF boycotted the original referendum and an agreement was only reached in 2014 and implemented two years later. Still not everyone followed suit – including the Maute Group, as we now know – and fighting continued. To this day, pirates, drug cartels, human traffickers and terrorist groups are particularly dangerous in certain areas, in ARMM and also in Zamboanga Peninsula.

What is striking about this history, is the length of time required to solve problems, the constant struggles and successive waves of hard-to-control breakaway insurgents. Duterte came along in 1986 and, as the longest serving Mayor of Davao – he served 22 years – and as the leader in the biggest city in Mindanao, Davao has 1.9 million residents, he gained a solid reputation for solving endemic security problems.

We, in the West, need to recognize that he was a game changer. With his strongman methods, though widely decried by human rights activists abroad, he has managed to bring “law and order” and overcome the scourge of drugs in Davao, no doubt at the price of many innocent lives. But the results were there and, unsurprisingly, he won the Presidency a year ago, the oldest person (71 years old) to do so.

While Duterte’s current War on Drugs in Manila is gaining international attention and public reprobation in the West, his offensive against insurgents in Mindanao went largely unnoticed – yet he launched it at the end of last year, targeting Abu Sayyaf and other rebel groups. At first, it was presented as a campaign to restore public order but lately Duterte has acknowledged that ISIS is behind the insurgency and he has warned that the battle of Marawi is part of an IS campaign to establish a base in Mindanao.

Why Marawi and How the Maute Group Fits In

Founded in 2012 by Abdullah Maute, one of seven Maute brothers, it is a jihadist group with the objective of installing an Islamic caliphate in the Philippines based on strict shariah law. In April 2015, the Maute pledged allegiance to the IS along with another terrorist group, the Ansar Khaliffa Philippines organization.

The Maute brothers started as guerillas belonging to the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF). Their links to MILF were close, including through marriage. They are first cousins of Azisa Romato, the wife of the late MILF Vice Chairman for Military Affairs Alim Abdul Aziz Mimbantas. But they broke off from the MILF because they disapproved of the negotiations started with the Philippine government that led to the 2014 peace deal.

Other Moro militant groups joined the Maute in their rebellion, notably Abu Sayyaf and BIFF, the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters, and soon the Maute attracted foreign terrorists from Indonesia and Malaysia. In the battle for Marawi, many more foreigners were found to participate, from Chechnya, Yemen and Saudi Arabia. As I write, the Filipino government has announced that another 40 foreign terrorists, from Arab countries and elsewhere, have recently managed to infiltrate the country.

Marawi was not the first important battle this group engaged in. The first was in February 2016 in Butig located in South Lanao province, the Muslim heartland of Mindanao where the Maute had their headquarters – and lost it to government troops. It is no coincidence that the Maute were in Butig: the town is also home to the MILF headquarters. Omar Maute, one of the brothers was reported killed at the time but that turned out not to be true, he was later caught on video in Marawi.

Yet, in spite of the loss of Butig, the Maute didn’t lose their means of revenue, a mafia-style protection racket, made possible by a weak or non-existent government presence. A sign of how active the Maute group was came a couple of months later: In April 2016, they abducted 6 sawmill workers and, in true ISIS style, beheaded two of them.

Who are the Maute brothers? Tracking Terrorism Org. describes them as “petty criminals” when they founded their group in 2012. Presumably, that makes them well versed in the dark art of “pizzo”, the word used in Sicily to describe ransoming business under the pretext of “protection”. And, inevitably, like the Sicilian mafia, they engage in lucrative drug trafficking. In fact, last month, government troops came across a load of what Filipinos call “shabu” (drugs) and other drug paraphernalia in the house of ex-Marawi City Mayor, previously occupied by the Maute leaders.

But they are more than petty criminals, they are equally well versed in the dark art of terrorism and, like ISIS, show social media savvy. They are adept at attracting the young, including university students and even children, to training camps where they prepare them for jihad.

They get military equipment from their terrorist friends but most worrisome is their long-standing affiliation with Jemaah Islamiya (JI), the lead Southeast Asian Islamist terrorist group that has cells in Thailand, Singapore, Malaysia and of course the Philippines. JI, a 5,000-member strong group, attained grim fame with the 2002 Bali bombing that killed 202 people, mostly tourists. The links between the Maute Group and JI run deep, since MILF and JI have themselves been in close contact since the early 2000s. Likewise, JI is linked to many other terrorist groups, including Abu Sayyaf and BIFF. All are followers of the fundamentalist, austere Wahhabi doctrine that has its source in an 18th century Saudi Arabian preacher who forbade, inter alia, the veneration of saints and visiting their tombs – hence the destruction of holy sites at the hands of ISIS.

The Maute first hit the Philippine news in September 2016 when they bombed a street market in President Duterte’s hometown of Davao City, killing 14 people and wounding dozens. They were also blamed for a failed bomb attempt near the American embassy in Manila in November 2016. But what distinguishes the Maute from other militant groups is their ability to attract university students, in particular from Mindanao State University in Marawi.

As a result, the Maute have built the most educated militant group in the Philippines. Two of the Maute brothers are well educated themselves: they started school at the Dasalan College (that they did not hesitate to burn down in Marawi) and completed their university education abroad. Omarkhayan Romato Maute attended the prestigious Al Azhar university in Egypt and married an Indonesian, the daughter of a conservative Islamic cleric; his brother Abdullah studied in Jordan and has personal links to Arab extremists. Hence the link to radical Abu Sayyaf.

What Next

Martial Law: Duterte’s first reaction on 23 May was to place Mindanao and its nearby islands under martial law, starting on May 23, 2017. This was announced during a briefing held in Moscow, where President Duterte was on an official visit, and will be in effect for 60 days – thus ending on July 22. That’s two days before the President’s State of the Nation address.

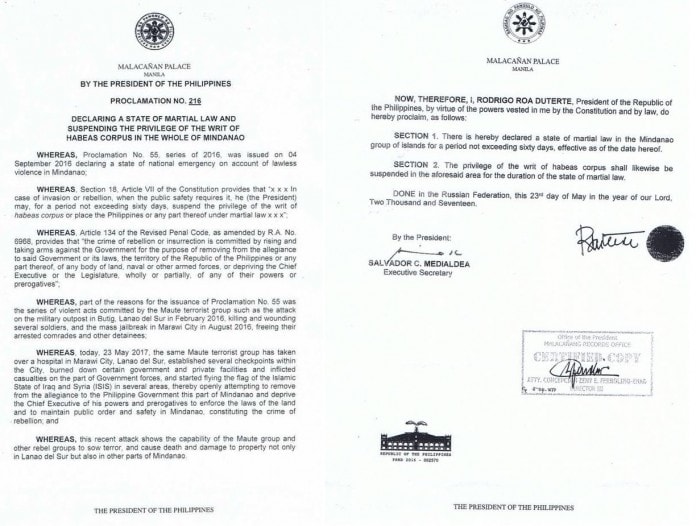

In the Photo: Martial Law declaration: Credit: By Office of the President of the Philippines (Rodrigo Duterte) (Concept Central)

Duterte has been criticized for not limiting martial law to Marawi, and even for having instituted it at all. People, especially in Manila, have vivid memories of suffering from abuse because of the martial law imposed by the dictator Ferdinand Marcos as a means to solidify his power. But Duterte is not deterred and he has aired the possibility of extending it beyond two months, even after Marawi comes back under government control.

It should be highlighted, however, that the martial law now in place with Duterte is very different in nature: The 1987 Constitution, adopted following Marcos’ ouster, made sure that the instrument of martial law could not be used again for dictatorial purposes: it is limited both in time and in scope. There are constitutional safeguards against the abuse of martial law including the possibility of a review by Congress of a President’s declaration, and, normally, there is a 60-day limit – unless Congress, in joint session, decides otherwise.

In fact, most Filipinos support Duterte and his latest approval rating would make Trump dream: 78 percent are generally satisfied with him and, specifically regarding his martial law, 57% support it as declared while 29% would have preferred to see it circumscribed to Marawi City and the surrounding region of South Lanao, according to a Social Weather Stations recent survey.

Nonetheless, the opposition to the government made a petition challenging the basis for the declaration before the Supreme Court. The latter, however, left the situation unchanged, in a ruling on 4 July that reads in part: “Until now the Court is in a quandary and can only speculate whether the 60-day lifespan of Proclamation no. 216 could outlive the present hostilities in Mindanao.”

Two weeks later, on 22 July, at the request of Duterte, the Congress, in a special joint session of both the lower House and the Senate, voted to extend Martial Law in Mindanao to the end of 2017. That’s a five-month extension and it required a special joint session of the House to approve it. The vote, overwhelmingly in favor (261 to 18) gives a measure of the legislators’ strong support for Duterte’s policies.

The War on ISIS to Go on as Long as Needed: As the standoff in Marawi is entering its third month, there is little doubt that Duterte is determined to go on as long as needed to defeat the rebels in the Southern Philippines and restore peace and order. Skirmishes continue to occur outside Marawi: the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF) staged a surprise raid mid-June on a village 190km south of Marawi, underscoring the challenge of reining in the spread of Islamic militants. Reports are that nearly a thousand ISIS insurgents are “holding 23 people hostage elsewhere in the south”. At least, those were the reports that were circulated at the time Congress approved the extension of the Martial Law, no doubt helping its quick approval.

Duterte has made it abundantly clear that he will, under no circumstances, negotiate with any and all insurgents, whether ISIS-linked or Communist rebels like the New People’s Army. A recent attempt by one of the Maute brothers to exchange his parents, currently under government custody, with the Catholic priest he holds as hostage has come to naught. “For what (the militants) have done, there will be no quarter given, and no quarter asked,” Mr Duterte said on June 27 at an event to mark the end of the Eid al-Fitr Islamic holiday.

Duterte can count on the general support of the Muslim population, many videos online show the Marawi people terrified and in distress and being helped. Datu Abul Khayr Alonto, former mayor of Marawi, Moro National Liberation Front leader and current chairman of the Mindanao Development Authority, warned of the dangers of signing up to the Islamic State in an impassioned speech: “Your government, the president of Philippines, Rodrigo Duterte did not declare war against the good people of Marawi,” he said. “He didn’t burn your own homes.” And he warned them: “They will come to you with beautiful language, they will even read the Koran to you … but don’t touch them because they are the dogs of hell.”

Given that kind of support, the proposal of establishing a Muslim Register as a policing instrument seems to be singularly unhelpful. Human Rights Watch (HRW) was quick to describe it as “collective punishment.” In an article published on their website, HRW pointed to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights which the Philippines subscribes to and which prohibits discrimination based on religion. My take is that this Muslim Register proposal is still born. Such registers a reminder of the Nazi infamous David star that Jews were forced to wear – never work, and Duterte is too much of a pragmatist not to know this. Moreover, many of the Philippines international allies are Muslim countries or have large Muslim populations and they would not take kindly to it.

Duterte is in fact busy playing the international card against ISIS and obtaining early successes.

Support has been forthcoming from all the major powers present in the region, notably Australia, China, India, the ASEAN countries – especially Malaysia, Indonesia and the Sultan of Brunei – and the US.

Support includes closer intelligence, military advice and equipment to varying degrees, and offers to train soldiers in urban warfare (the Philippine Constitution bars foreign troops from combat). For example, in June, China delivered the first batch of arms and ammunitions; Australia deployed two hi-tech AP-3C Orion aircrafts to provide surveillance and offered multi-level training; the US military brought one P3 Orion surveillance aircraft and drafted in special forces to assist the Philippine military in an advisory capacity. Duterte, despite his antagonistic stance toward Washington, has acknowledged the US assistance is helping save lives. Meanwhile, Duterte is still waiting on Russia, and in a recent speech, he indicated he had not lost hope, “I don’t know about Russia but Putin, sabi niya tutulong siya (he said he would also help)”.

The New-found Role of India: One country stands out and it is, surprisingly, India.

India has rushed financial assistance of $500,000 (25 million pesos) intended for relief and rehabilitation in Marawi, the first time India is sending such aid to another country in the context of fighting terrorism. This contrasts with China’s gift of just 15 million pesos in aid.

It appears that India’s new “Act East” policy is driving this unexpected India assistance. It comes at a time when the Philippines is getting ready to host the ASEAN-India foreign ministers meeting in Manila in August, which will mark the 25th anniversary of ASEAN-India relations. This will be followed by the annual ASEAN-India summit and the East Asia Summit in November, where combating terror is expected to figure high on the agenda. India is also expanding its counter-terror partnership with Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand,

It appears that India’s new “Act East” policy is driving this unexpected India assistance. It comes at a time when the Philippines is getting ready to host the ASEAN-India foreign ministers meeting in Manila in August, which will mark the 25th anniversary of ASEAN-India relations. This will be followed by the annual ASEAN-India summit and the East Asia Summit in November, where combating terror is expected to figure high on the agenda. India is also expanding its counter-terror partnership with Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand,

In short, the whole of South East is mobilizing, and the driving force is India, not China. With the Philippines welcoming everybody in Manila.