Educated as a medical doctor, the German-Egyptian Dr. Gindi turned to art in 2013, graduating from the Florence Academy of Art Sculptor Program, Italy. Known as a classically-trained sculptor based in Switzerland, she works with clay, bronze and other materials to explore the complexity of human existence. She has had several exhibitions abroad, including Italy, Germany and China and is a member of the New York-based National Sculpture Society. Dr Gindi was a finalist at the 2021 International Art Salon (Port Reading, New Jersey) and was preselected for the 2021 Figurativas Painting and Sculpture Competition of the European Museum of Modern Art (Barcelona).

Impakter was able to talk to Dr. Gindi and here is the interview, edited for brevity and clarity.

Several things are very striking about your life. To start with, what made you turn from the life of a doctor to that of an artist? What was the defining moment that made you change so dramatically?

Dr. Gindi: My relationship to art was always natural as I felt the vital necessity to create in everything I do. If I do not create, I get sick: emotionally and physically. Curiosity defined my nonlinear educational path. I was educated as a medical doctor and worked as a General Practitioner in various countries, yet the more time I spent working as a doctor, the more I wanted to reflect on what I was experiencing, particularly the fragility of the human being.

By realizing and grasping the ultimate infinity inherent with our own life we can act and live fearlessly.

At one point of time, my inner urgings just told me what to do – I followed my vocation, I enrolled in a three-year formal education in classic sculpting at the renowned Florence Academy of Art and I finally became the sculptor Dr. Gindi. From the onset, it was clear for me that I wanted to model the potential infinity of our existence as I yearn to illustrate humanity beyond transient flesh and bones. I believe sincerely that life is endowed with peerless sanctity. By realizing and grasping the ultimate infinity inherent with our own life we can act and live fearlessly.

You have a fascinating dual cultural background: Germany and Egypt. You now live in Switzerland and you have extensively traveled abroad, including Egypt of course, but also Italy where you studied art, France, Hungary, Germany and even as far as China. Can you tell us a little about the reasons for all these travels and how you reacted to the different cultures you encountered, what you learned?

DG: Indeed, I might be characterized as a restless spirit as I try to create the world that I perceive, over and over again. Motivated by the desire to experience the bounty of imaginatory territories, I spent my entire life wandering around different cultures – wanderlust exemplifies the lexicon of my being.

As a matter of fact, my sculptures mirror the potential answers to questions I encountered during my inner and outer life travels. My sculptures seem to ask – Who am I? What is my role? Where shall I go? Is there a sublime that eventually I can attain? Or shall I submit to fate and just resign?

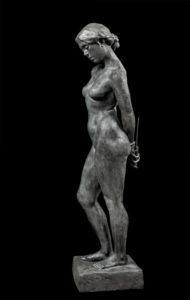

Take for example Sancta’s Broken Halo, one of my latest works, which was inspired by the memory of a female orthodox icon in the house of my grandmother in Cairo – as a child I feared and loved this icon at the same time: a Holy Madonna, who was illuminated at night. She looked as though she was from another world, and so Sancta’s Broken Halo shows a young woman wearing an injured nimbus of light. She is blessed by the divine, she is radiating bliss. But is she silently waning away? We don’t know where her travels will lead her. She is confronted with the most irreducible fact: the ambiguity of being.

Sancta, like all of us in our life journeys, is trying to solve the mysteries of existence.

In your article ‘The Intrinsic Allure of Infinity’, you explain that you are ‘perpetually drawn to all objects’ in your surroundings. Would you say this extends to a feeling of connection to the natural world?

DG: With my sculptures, I want to show the choices we have in life. And I hope that we take the right decisions in moments of conjuncture, achieving the shimmying state of infinity, the endlessness of time and space in a natural world.

Take for example my recent oeuvre The Fateful Choice. Deep in contemplation, a young woman is at the same time musing, and experiencing a sense of elation. Then on awakening, is a frail stranger to herself. A knife is held behind her back, and she and the fatal tool are together until only the memory of her choice remains. She is at a turning point of her life – is she connecting to the natural world or succumbing to the chimera of wan indifference? We don’t know if her fate is drifting in the one or the other direction.

The nature of human existence can be traced to such fateful choices. A wrong decision can destroy the integrity of the natural world.

On the topic of fateful choices, what do you consider to be the challenges to a creative process when trying to work in a sustainable way – for example sourcing and working with materials?

DG: My sculpting is confined to the modelling of the subject in clay. This soft, sensual, organic material has for thousands of years been crafted into artefacts, and then is cast into bronze. The hand-building requires time, experience and patience, it cannot be taylorized. The clay model is finally casted into bronze which I have chosen for its permanence and its vibrational traits, as well as its ability to lock and reveal placed ardor.

I have to admit that the casting process – which is done by a foundry – is partly toxic by inhalation and ingestion. I am currently searching for bronze source materials which are more environmentally and health-friendly.

Still, there is something intrinsically natural about bronze, especially the alloy. You can touch the skin of your sculptures; it is part of you and it embodies and imbues the personality of the spectator. Bronze has an eerie element of perseverance – it can last for thousands of years and it ages gracefully, acquiring with time a variety of finishes due to the intensity of the patina and how it interacts with the environment.

Although at different times, we both attended Freie Universität Berlin where I spent my time improving my language skills and sampling Berlin’s nightlife. How did the cultural zeitgeist of the 1990s influence your art and practice?

DG: I lived in Berlin during my early 20s when I studied medicine. A concrete ugly monument – the Berlin Wall – physically and ideologically divided Berlin. I was living in the Western part, 600m surrounded by a repressive regime.

West Berlin served as a shining beacon of freedom and creativity wherein I experienced the city’s incredible subcultures, ranging from the punk movement to experimental art – West Berlin was a habitat for alternative conducts. My time there was a life of discovery and will always continue to influence me.

Related Articles: Oozing Sculptures: An Interview with Dan Lam | VR and 3D Printing Startups Bringing Sustainability To Museums | Coronavirus and Art: How Quarantine Impacts Museums

After my daily medical studies, I visited museums and galleries before diving into the city’s flashy nightlife. Inspired by the naughtiness of the city’s hedonism I learned to follow my own instincts, a learning experience which still holds true today in my artistic process. I am trying to create the kind of works I believe in.

Ultimately, it is more about purpose than mere appearance. We sculptors don’t have to follow any fashion.

Your last exhibition was hosted online by The Florence Academy of Art, and will have been experienced by your audience in a markedly different way. As a semblance of normalcy returns to society, what are your plans and what excites you the most about your future and your work?

DG: Most artists have always been driven into hermetic practices as they spend long hours in their studios, secluded from the fault lines of this reverberating world. I am no exception – I am revitalized when entering my studio, starting to follow my unconscious, listening to the clay.

The pandemic accentuated this practice, it turned us artists into full-fledged hermits as we couldn’t communicate with our audiences via exhibitions in the traditional way. But I have to say that virtual exhibitions were a good alternative to communicate beyond notions of time and place.

My personal yet universal experience of isolation led to an exponential increase in using social media which was very enriching. I believe that the virtual outreach is here to stay after the pandemic and will augment the artistic experience. But we are also going back to face-to-face exhibitions, and I very much look forward to collaborating with galleries as well as private collectors in the months to come.

I hope that my sculptures will continue to excite in an unexpected way, even if that feels irritating at first. But it is not about this initial encroachment: in the end, my sculptures should make sense and have the urgency and presence of something that is simply infinite. Something that always existed, and that will continue to exist.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: Dr Gindi. Photo Credit: Dr. Gindi.