How to Address the Tech World’s Moral Blindness

Who leads the tech world and what is their impact on the economy? Put together two remarkable statistics:

- Of the ten richest men in America, only three are not tech billionaires: Warren Buffett and the Koch brothers;

- Tech firms represent 21% of the 500 largest American firms, yet they employ only 3% of the workforce (Guardian, 2017);

and you get an exact description of the New Golden Age.

We’ve moved from the Robber Barons of the 1900s to the tech billionaires of the 2000s. Same concentration of wealth, same political and economic power, same income inequality, same moral blindness – with one big difference that hurts the working class: compared to the Robber Barons and the manufacturing giants of the 1950s, they create very few jobs.

Worse: The ‘frightful fives’ – Apple, Google (Alphabet), Amazon, Microsoft and Facebook, as noted by the New York Times’ columnist Farhad Manjoo – are gobbling up start-ups, buying out the most successful rather than allowing healthy competition to develop. This puts the very process of innovation at risk. Instagram, WhatsApp, DeepMind are some of the better-known examples.

The rise of tech is affecting not just the economy, but our politics and culture too, twisting and straining the moral fibre of our society. In his 2016 speech at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial, Obama somberly noted that “technological progress without an equivalent progress in human institutions can doom us”. And he reminded us that “the scientific revolution that led to the splitting of the atom requires a moral revolution as well.”

The moral revolution certainly has not arrived in Trump’s America, focused for now on its America First agenda, denying climate change and trying to rebuild the coal-based manufacturing of the 1950s instead of addressing the real challenges of the future. Challenges that stem from tech industry AI products, robots and supercomputers, displacing jobs and ruining the middle and lower classes.

RELATED ARTICLE: HOW TO REVIVE THE AMERICAN DREAM, A CLASS DISPUTE by Claude Forthomme

Tax havens are a big part of the story.

After the Panama Papers, we now have the scandal of another offshore firm, the Appleby files. Among Appleby’s long list of ultra-rich clients, including 31,000 Americans, we find a range of businessmen, pop stars and royals, including George Soros, the financier and philanthropist, Carl Icahn, the equity investor, Sheldon Adelson, the casino magnate, Madonna, Bono and even (for the first time) Queen Elizabeth II. Inevitably, we find tech titans like Microsoft co-founder Paul G. Allen.

In the Photo: From left to right, Paul G. Allen, George Soros, Bono and Queen Elizabeth. Source: Wikimedia commons.

While bashing the tech industry on moral grounds has become fashionable, how useful it is in curbing it is debatable. After all, the tech industry has changed our lives, sometimes for the worse, to be sure, but also for the better. And the industry has many friends and supporters, not to mention ample lobbying power both in Washington and Brussels. And so long as the industry is making money, criticism, however right and morally grounded, will fall on deaf ears.

There are other ways to curb the tech industry and ensure it becomes a responsible citizen.

Europe’s Fight Against Tech Titans

Europe is leading the way, propelled by its experience of two devastating world wars. Totalitarian regimes, from Nazism and Fascism to Soviet-style communism, have taught Europeans to value three fundamental principles:

- equity, e.g. ensuring an equitable tax system and fair competition rules;

- the right to privacy, including protecting personal data from commercial use; and

- truthful news, as opposed to fake news, false claims, lies and propaganda.

Whether the “moral revolution” has arrived in Europe is debatable, but one thing is certain, the above-mentioned values have enormous political weight on the continent. Social media and Facebook especially have been regularly accused of not doing enough to curb the spread of fake news, an issue that was addressed at length in an Impakter essay last year. Impakter has also explored in several articles the threat Internet giants pause to the right to privacy, again with Facebook at the heart of the debate (see related articles below).

Here we will explore the issue that the tech industry tends to flout: equity.

The Real Battle: Equity and the Creation of a Level Playing Field

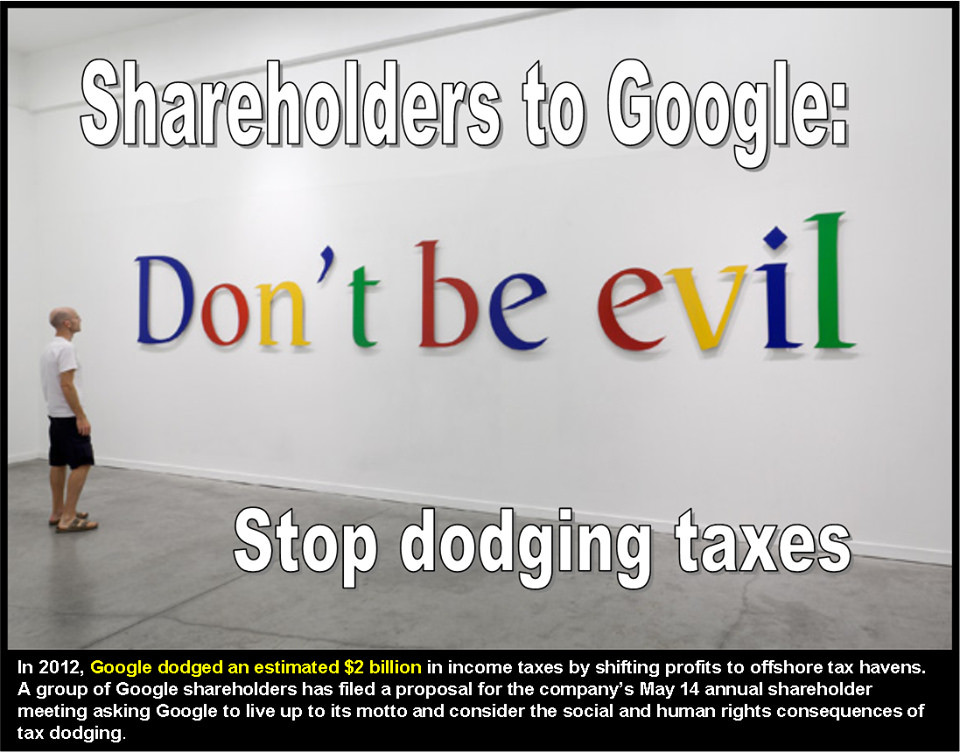

It is not enough for Big Tech to announce, like Google has from the time it was founded (1998), “Don’t Be Evil”. The tech industry should live up to what it says and start to act morally. It should pay the taxes it owes, play by the rules of fair competition and stop prying into people’s lives, using the information to rake in tons of money with advertisers. Those are the feelings that are driving European action against the tech industry.

The tech industry should live up to what it says and start to act morally. It should pay the taxes it owes, play by the rules of fair competition and stop prying into people’s lives, using the information to rake in tons of money with advertisers.

There is, however, a misconception in America about European action against Big Tech that needs to be dispelled. In 2015, when the EU Commission started its antitrust activities against American tech corporations, investigating Google and Qualcomm for allegedly abusing their dominant market position, many people in the US felt the EU Commission was driven by protectionist concerns for homegrown tech companies. In an interview with Recode in 2015, President Obama said that “sometimes the European response here is more commercially driven than anything else”, suggesting that “oftentimes what [are] portrayed as high-minded positions on issues sometimes [are] just designed to carve out some of their commercial interests.”

This is a simplification and even in America the tech industry’s propensity to gain monopoly positions and avoid paying taxes is a cause for concern, as this 2012 poster shows:

Photo Credit: Citizens for Tax Justice, Flickr

European attempts to create a ‘level playing field’ for tech companies are genuine. And we don’t know yet how the EU antitrust probes will play out in the end or whether Google and other tech giants will settle with the Commission – the fight is on-going.

So far, the Trump Administration’s stance on anti-trust, judging on what is happening in the matter of the AT&T and Time Warner merger, is not cut and dried. After Trump initially took a position favourable to the AT&T merger, the Justice Department’s antitrust enforcement arm flexed its muscle, asking AT&T to divest itself, inter alia, of CNN – immediately drawing concern that it was taking Trump’s side in his own personal battle against CNN journalists.

Whatever the case, one thing is certain, as noted on Conversation by Peter K. Yu and John Cross, two American professors of intellectual property law, EU antitrust action has opened the door to similar activities in other countries, for example, China fined Qualcomm in 2015, and Taiwan did the same in 2017.

Some critics feel that antitrust action may even be unnecessary in the face of rapid technological change. That was the view expressed by Farhad Manjoo in a 2015 New York Times article, arguing that with technological progress, consumers rapidly moved to new products, thus ensuring that any monopoly position is short-lived. Giving the antitrust ruling against Microsoft as an example, Manjoo argued that this would make such rulings against tech giants unnecessary. Whether he still feels that way is open to question now that there is growing evidence that ‘platform capitalism’, with its characteristic tech network structure, has an innate tendency towards monopoly (or oligopoly).

SEE RELATED ARTICLE: PLATFORM CAPITALISM, THE ECONOMY OF THE FUTURE? By Claude Forthomme

Yet, despite the EU Commission’s antitrust efforts, not too many nations in Europe have yet moved against the tech industry. Are we too mesmerized by its explosive growth, perhaps longing to participate in its unparalleled success without realizing the damage being done?

Several European countries, foremost among them historic tax havens like Switzerland and Liechtenstein but also within the EU, Ireland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Belgium and the UK (e.g. Isle of Man), have given a warm welcome to Silicon Valley giants (and big businesses in general), helping them to use all available loopholes in their tax system. The City of London’s 9,000 tax advisers and accountants provide tax management services to corporations and bill them £2 billion in fees annually.

But the EU Commission is undeterred, and it has recently launched a major antitrust action against Google and a two-pronged attack on tax issues. The driving principle behind its fiscal action is to tax internet companies in the countries where they generate their business instead of letting them shift profits to low tax jurisdictions.

Thanks to the efforts of one determined fighter, Margrethe Vestager, EU Commissioner for competition, things are beginning to change.

In the photo: Margrethe Vestager, EU Commissioner for competition Credit: This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY-ND

In June 2017, she managed to slap a €2.4 billion ($2.9 billion) antitrust fine on Google – the highest fine ever in the history of the EU Commission – for abusing its dominance in general internet search markets in Europe (its share is 90 percent) to favour its own online shopping services.

Google had 90 days to stop its illegal activities and reform or face fines of up to €10.6m a day, which is the equivalent of 5% of the average daily worldwide turnover of its parent company Alphabet. A few days short of the deadline, on September 11, Google lodged an appeal against the ruling with the EU’s Court of Justice in Luxembourg.

Any such course of action would take years before the Court reaches a decision, but Google was encouraged by the Court’s position that had just emerged on another antitrust case involving a €1.3 billion ($1.4 billion) fine against Intel: It had ended badly for the EU Commission, with a decision to send the case back to be re-examined by the lower courts.

The appeal notwithstanding, Google did not ask the Court to suspend the antitrust ruling and it appeared to fall in line with the Commission’s demands, presenting EU officials with a plan, an ‘antitrust compliance proposal’ to amend its practices. In an initial review, the proposal met with their approval, Ms Vestager said it was a “step in the right direction”.

But the fight against Google doesn’t stop there. Google faces two other antitrust cases as the EU is investigating potentially anti-competitive practices related to the Android operating system and AdSense advertising platform. Both investigations should conclude in a few months and it is widely expected that they could lead to additional fines.

Undeterred, on 4 October 2017, Ms Vestager ramped up her battle royal against the big tech companies and the countries that host them with two more strategic moves:

- FIRST MOVE against Apple and Ireland: The European Commission decided to refer Ireland to the European Court of Justice for failing to recover from Apple illegal State aid worth up to €13 billion, as required by an earlier Commission decision.

In the Photo: Apple Headquarters in Ireland. Credit: Photo by Unknown Author licensed under CC BY-NC-SA

- SECOND MOVE against Amazon and Luxembourg: The European Commission concluded that Luxembourg granted undue tax benefits to Amazon to the level of some €250 million (about $293 million). This is illegal under EU State aid rules because it allowed Amazon to pay substantially less tax than other businesses. Luxembourg must now recover €250 million.

In the Photo: Amazon Administrative Offices in Luxembourg Credit: St James Gate Flickr

The Core Issue: Tax Havens and Special Zones, a New Kind of Globalized World

Can the EU successfully force tech giants to pay their taxes? Or, as one loophole or tax haven closes, will tech giants move out and find another?

This is the core issue; the battle doesn’t concern just tech giants, but all big corporations in all industries. And it is a battle that transcends national boundaries.

Tax havens and “special zones” have grown exponentially since the 1960s, when there was only a handful of them, tax havens like Bermuda and the Caymans or historic cities like Hong Kong and Singapore, that offered special, highly favourable tax deals to attract investors.

Since then, the model has been copied around the world (including in the US, where cities routinely offer tax breaks to big foreign investors). By 2006, tax havens and special zones had proliferated to the point that they numbered some 4,000 according to geographer Gareth A. Jones (see the remarkable chapter he wrote for After Piketty: The Agenda for Economics and Inequality, a fascinating collection of essays by major economists, edited by Heather Boushey, Executive Director of the Washington Center for Equitable Growth).

Such extra-legal spaces, comprising offshore and onshore jurisdictions, including zones, corridors and cities, both old and new, fall beyond the purview of states and international or UN governance, empowering corporations and plutocrats, thriving on secrecy and threatening the workings of democracy.

In his After Piketty chapter, Gareth Jones criticizes Piketty for “underplaying the financialization of the economy”, overlooking the fact that over the last 40 years, the world has totally changed with the rise of “high-income-and-wealth holders” dominating people in the middle and lower classes, helped along by the neo-liberal “pushback on political regulation of capitalism” since the 1970s.

Among the stunning statistics, Gareth Jones points to:

- The “registration of companies in low-tax jurisdictions” was found by the OECD to cost the treasuries of G-20 nations as much as $240 billion annually; to put this number in perspective, consider that for 2018 the US federal government in its latest budget estimate expects the deficit will be $440 billion – and remember that most companies using tax havens are American;

- “A person, company or investment vehicle such as a trust might be registered offshore in one or more than seventy tax havens” yet they might show up with “no more than a postal address (colloquially known as a letterbox)”;

- The exponential growth of the model since the 1980s, with a ten-fold increase by 2010, as some 20 percent of US corporate profits are booked in tax havens, according to recent research by Gabriel Zucman.

In this new globalized world where national borders are porous and corporate titans escape fiscal authorities, does the EU, as a supranational organization, stand a chance to win? In principle, it is in a good position: the EU Commission’s mandate covers 27 countries that happen to be the world’s most attractive market – nearly half a billion people with a good average income and education – a market that the tech industry (or big business) cannot afford to miss out on.

In practice, the EU position is not so good: it’s not yet a strong supranational organization, the tax systems of EU member countries are not aligned, and Ireland with its 12.5% corporate tax rate that is well below the EU average literally ‘gets away with murder’ (even if the Irish government denies this) – or at least it is causing permanent damage in the EU fiscal system, enabling tech titans to walk away scot-free.

A Modest Proposal – Going Beyond Micro-levies

Micro-levies have been proposed, most recently by Saadia Madsbjerg, managing director of the Rockefeller Foundation in a New York Times article, suggesting for example, that a small tax (say 0.8 percent) be levied on the data brokerage industry (it rakes in the personal data we leave behind online), an industry that generates more than $150 billion in revenue each year and is expected to reach $250 billion in 2018.

Micro-levies have been shown to work in the past, as Madsbjerg reminds us:

“Over the last decade, the governments of 10 countries, including Chile, France and Niger, have successfully raised more than 1 billion euros in funding from a tax on airline tickets of €1 to €40 depending on the class of ticket. The money generated has gone toward global H.I.V./AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria eradication programs.”

The problem with micro-levies is that even if they do work, the revenue they raise is modest, and, because of the low impact, they do not work towards modifying tax structures or curbing corporate tax avoidance.

Something more decisive is needed. What I propose as a solution to end corporate tax avoidance may seem radical to some, even counter-intuitive, but it may be in the end the only one that will work.

Consider this: What if the EU, instead of forcing Ireland to bring up its corporate tax rate to the average EU level, would instead negotiate to allow all tax rates to move closer to the Irish level, at some appropriate in-between point, say 16 or 17 percent. This would encourage Ireland to comply with EU rules, but in return, the EU should demand that all loopholes be closed, including for example the clever “double Irish with a Dutch sandwich technique”.

This two-pronged approach would achieve two goals: provide Europe with a single fiscal system and do away with all the tricks and loopholes to avoid taxes, while leaving corporations facing much less exacting overall tax rates than in the United States.

All it requires is a different negotiating mindset on the part of the EU Commission, a willingness to abandon its attachment to historic tax levels and start thinking differently, focusing on loopholes elimination instead of maintaining high tax rates.

Could it work? Maybe. After all, many business tycoons have shown a strong moral fibre: It was Warren Buffett who was the first to ask for a higher, fairer tax system, famously pointing to the fact that he was paying proportionately less taxes than his own secretary. And the news is just out that some 400 wealthy Americans have signed a joint letter asking Congress not to cut their taxes.

At least it would be worth a try.

RELATED ARTICLES: IMPAKTER ESSAY: WHY FAKE NEWS GOES VIRAL AND WHAT CAN BE DONE ABOUT IT by Hannah Fischer Lauder

INTERNET OF THINGS: THREAT TO OUR PRIVACY? By Alessandro du Bessé

A EUROPEAN PATRIOT ACT? A PREVIEW OF EUROPEAN INTERNET SECURITY IN 2016 by David Pingree

PROFILA: A CONSUMER’S DESIRE FOR PRIVACY AND DATA by Alessandro du Bessé