In his early twenties, David Sheen left his job as a graphic designer to find a more fulfilling life. While living in a Kibbutz in Israel, he discovered natural building and was so taken by the concept that he dedicated the next several years of his life to studying ecological architecture. Over this time, he traveled the world and created a documentary about natural building. The documentary, “First Earth”, was published by PM Press in 2010 and has been translated into a dozen languages. Today, David works as an independent journalist, filmmaker, and speaker out of his home in Dimona, Israel. Here, he tells his story.

How did you become interested in ecological architecture?

It began in the year 2001 when I was living here in Israel. After a few years of working as a graphic designer, I didn’t feel like I was making myself happier and I didn’t think I was making the world a better place. I came to the conclusion that I didn’t want to work for another 25 years to save money, so I could then leave the city to live a lifestyle that would be healthier both physically and spiritually. I decided that I wanted it now.

I grew up in the suburbs of Canada; I didn’t study agriculture and I wasn’t much of an outdoorsy person, so I never accrued any skills that I could apply to living on the land. But in Israel, I had another option to live on a collective farm called a Kibbutz. Most of them are no longer socialists like they once were, but some were, so I traveled around the country trying to find the Kibbutz that spoke to me, and I found one that I liked. It was in the deep south of the country, as desert as you can imagine. Sand as far as you can see, but also green spots where they had harvested the land to feed their date orchards. I liked that they were living on the land and that they were experimenting with natural building, so I moved out there and started living as a farmer and learning about how to build from the Earth. To me, it just blew my mind and I realized that people had been talking about how to eat healthy, but no one had been talking about how to build healthy.

How did you continue learning about natural building after this experience?

After a while, I realized that the Kibbutz wasn’t completely socialist, it was just socialist for Jews, and being someone who aspires for complete equality, I didn’t want to be apart of that anymore. But I was inspired by the natural building and decided that I was going to take that knowledge and the skills I had and channel them into learning how to build homes. But to do that, I had to learn what my materials were. I didn’t want it to be an intellectual exercise, I wanted to learn with my own hands what the materials were capable of and the only way I could do that was to have a practical experience.

So I moved back to North America and enrolled in a Masters of Architecture program at the University of Toronto. However, I quickly came to realize that you couldn’t learn how to build ecological architecture in a capitalist university; you’re just going to learn how to replicate what already exists. From my own research, I realized that the people who were at the forefront of the ecological building movement were mainly located on the west coast. So I decided that I was going to move out there and learn from these masters. I spent 6 months living in the woods in Oregon. I apprenticed at the North American School of Natural Building, and I learned how to build with my own hands and feet.

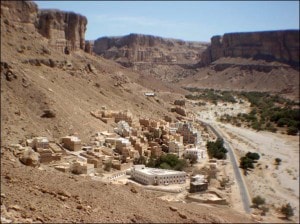

Later on, I decided to document the natural building that was happening all over the world. I worked to save up some money and then traveled to different countries, specifically the U.K., where there’s hundreds and thousands of Earth buildings that people still live in and work in today, Africa, where a third to half of the population lives in houses made out of Earth, and Yemen, where there are literally skyscrapers made from Earth that have been around for thousands of years. The purpose of the film wasn’t ever to make money. The purpose was to let the world know this was possible.

What surprised you most about natural building around the world?

First of all, being on the west coast really deeply influenced me. Because there the people who are involved in this movement, who want to build healthy homes, do so for spiritual reasons. They want to make the world a better place and make healthier lives for themselves and their families, but also for the ecosystem and the planet. For me that world did not stop at natural building. Natural building was the physical manifestation of how to make our structures healthier, but the time I spent on the west coast, being connected to these people, opened me up to all kinds of ways of being.

Because of my time here, the film isn’t just targeted towards people who want to learn some technical skill or who want some kind of logical explanation. It’s about speaking to something greater, it’s about a holistic lifestyle, it’s about extending health and equality and freedom to everyone.

The west coast is very much a capital of cultural change, but it was also interesting to go to other parts of the world where natural building isn’t about being on the cusp of a new culture or about being a post-capitalist society. In other parts of the world, it’s the old culture that always was and the people who advocate it aren’t radicals, they’re traditionalists.

What do you believe the benefits of natural building to be?

There’s lots of different ways that building in this fashion has a lower ecological footprint. Many of the materials are sourced locally, so you’re not using fossil fuels to transport the materials or to process them. Many of the materials are also breathable and non-toxic, so you’re not living in a home where you’ll be breathing in the off-gases. There’s also not excessive waste that is going back into the water, land and biosphere.

There’s also a spiritual dimension of it, which speaks to how you build it. The point is that you can do a large chunk of these tasks yourself and actually build your own home. None of these tasks are highly specialized and it is possible to learn a lot of these skills, even for people who don’t have experience with construction, as I did not.

That is incredibly empowering because we live in a society with a hyper-specialized economy, where most of us have hyper-specialized jobs. A couple hundreds of years ago, our ancestors carried out hundreds of tasks in any given week. You didn’t have to go to a specialized person to do things, sometimes you did, but most of the time you just knew how to do it yourself. If all of a sudden, we didn’t have this economy and this technology, for most of us, the skills we have and use everyday wouldn’t amount to anything and we wouldn’t be able to survive. To learn some of these basic skills gives you a sense of confidence and empowerment. That’s the incredible spiritual transformation you go through when you’re learning how to build your own home.

How do you foresee the future development of ecological architecture in society?

I hate to be a pessimist, but I am not very hopeful. Since I made this film, we haven’t seen a massive transition. It seems most politicians are still afraid to speak seriously about the major changes we’re going to have to go through to live in a post-industrial society. No one is tackling these issues because they will inevitability require humans to make do with less. Instead of downscaling, people still believe they can continue headstrong into the future and continue to upscale their lifestyles. Perhaps the only thing that will end this will be a complete collapse of the economy, which at that point it will be too late to build new infrastructure.

It would be amazing if we could just downscale into the way our ancestors lived 3 or 4 generations back, but because people aren’t starting to prepare for this time that is inevitably around the corner, we’re not going to go back a few generations, we’re going to go back a few thousand generations. It’s sad to me that society’s leaders aren’t making concrete efforts to shift our culture to a more ecological lifestyle. We’re going to have to do it soon enough when we are forced to, but by that point we won’t have hardly any of the resources that are necessary to make that transition as smooth and as easy as possible.