While 2023 will be remembered for some major breakthroughs in science and society, an alternative reality presents us with continuing existential risks of our own making. In combination, and if played out to extremes, these — especially climate change — could trigger a tipping point gathering strength, intensity, and potentially leading to irreversible impacts on life on our planet — our only home! As highlighted in a previous Impakter article, the decline of democracy, including associated structural systems failures — world crisis zones, biodiversity loss, autonomous robots, to name several, stands at the top of global agendas.

2024 is the biggest election year in history and democracy with more than 2 billion voters across 50 countries going to the polls, including Bangladesh, Taiwan, Pakistan, India, South Africa, Mexico, the European Union, the UK, Indonesia, the US, and Ghana…

To underscore and clarify what is at stake across global regions, this article focuses on five key questions:

-

- How are levels of liberal democracy determined across the world?

- How does autocratic far-right extremism impact on people’s lives?

- How can societal collapse be prevented?

- How can power be entrusted to the “right people for the right reasons?”

- How can society make a stronger case for liberal democracy?

Democracy today: Assessment criteria and global ratings

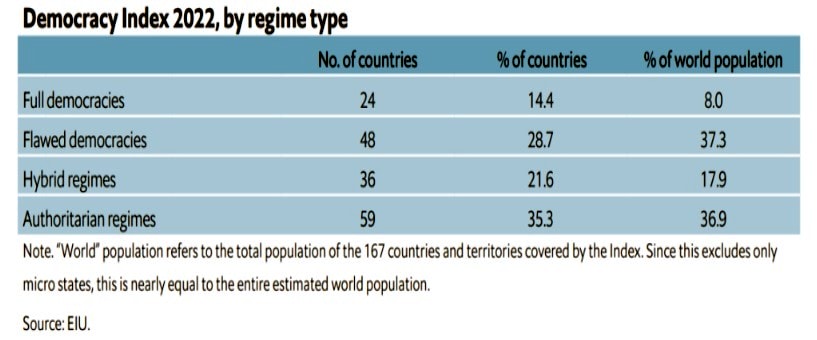

A snapshot of global freedoms is produced annually by the Economic Intelligence Unit (EIU). The Democracy Index (DI) applies five criteria to assess the extent to which 167 countries are democratic: (1) electoral processes and pluralism, (2) government functioning, (3) political participation, (4) democratic political culture, and (5) civil liberties.

Results for 2022 are shown below, confirming that “more than a third of the world’s population (8 billion people) is now subject to authoritarian rule and that only 6.4% now enjoy full democracy” with most living in flawed, hybrid and increasingly authoritarian regimes.

Similarly, but extending the country database, using the five criteria alongside 60 questions, Freedom House “rates people’s access to political rights and civil liberties in 210 countries and territories.” With full democracies ranked between 8.01 and 10.

In 2023, top ten country scores were achieved by Finland, Norway, and Sweden (all 100% — Political Rights [PR]: 40% and Civil Liberties [CL]: 60%), followed by New Zealand (99%), Canada (98%), Denmark, Ireland, Luxemburg, San Marino, and Netherlands (all 97%).

It is noteworthy that these nations are also the happiest countries in the world (2020-2022) according to the 2023 World Happiness Report. Could democracy be equated with happiness?

Of the 210 countries in the 2023 Freedom House report, the lowest country scores are North Korea, Eritrea, and the contested region of Eastern Donbas (all 3%), followed by Syria and South Sudan (both 1%).

Autocracy and the rise of far-right extremism

Simply defined, right-wing extremism is “anti-democratic opposition towards equality,” characterised “by racism, xenophobia, exclusionary nationalism, conspiracy theories, and authoritarianism” reminding us of fascism in the 1930s culminating in the Second World War.

Summarised below, trends and stressors in the past few decades have “galvanised” the drift toward the far-right representing a vast array of parties, movements, and groups in a number of countries not only in Europe but also in the Americas, Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. While these may differ in terms of ideologies and methods, according to the UK Trade Union Congress (TUC), they all share “emphasis on racial or ethnic and cultural superiority, rooted in the myth of natural inequalities and nostalgia for an imagined past.”

The greatest threat to society at large is that extremist far-right “ideas and influence have been mainstreamed,” normalising “division, exclusion and blame,” adopting “what is known as ‘nativism’ or ‘ethnic nationalism,’ asserting that “non-native (or ‘alien’) forces — people, institutions or ideas — pose a fundamental threat to the native population or native culture.”

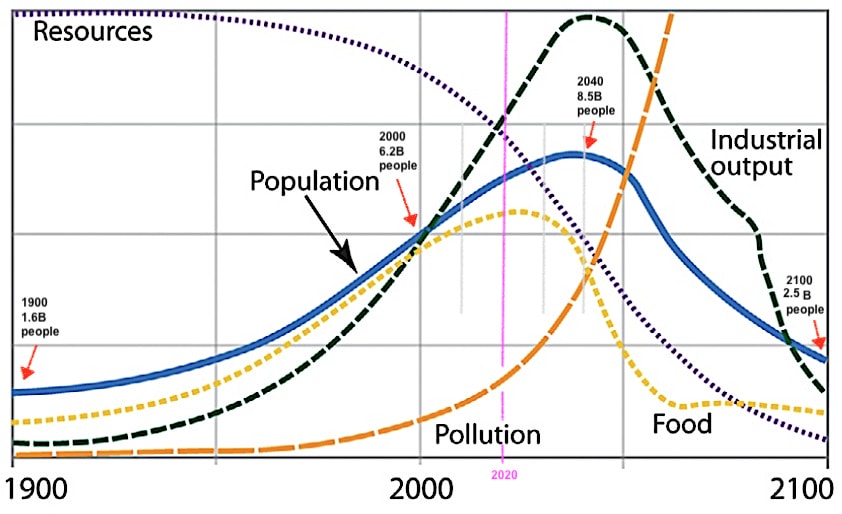

Factors that may be exacerbating the influence of far-right movements were emphasised in a fifty-year retrospective on climate change. Rather than being “on the right course as a species,” according to the vice president of the Club of Rome, Carlos Alvarez Pereira, we have not made any progress in the past seventy years with regard to “pollution, climate warming, biodiversity loss and global inequality.”

Our main failing, he asserts, is that “we are caught up in a “kind of maniacal, ecologically destructive growth at all costs that’s built into the system”: we are guilty of “burning the future…the least renewable resource”: creating “a system which is more debt-driven,” allowing “people in the value chain” to reap benefits from “the idea of scarcity,” while creating false hope that “technology will save us.”

Unquestionably, geopolitical tensions also play into the hands of far-right proponents who favour chaos over law and order, promote cultural intolerance, marginalise experts and undermine human rights.

As things stand, with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, growing conflict in the Middle East and over Taiwan as well as other “secondary crises in Venezuela, sub-Saharan Africa, Iran, the Red Sea, Indo-Chinese border, it is clear that the international order is under siege making the struggle for global political hegemony our greatest fear or concern.

In this regard, global decision-makers should be mindful of the iconoclastic economist, teacher and diplomat John Kenneth Galbraith, who reminded the world during the Russia-USA Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962: “A nuclear war does not defend a country and it does not defend a system…. not even the most accomplished ideologue will be able to tell the difference between the ashes of capitalism and the ashes of communism.”

Societal collapse

In his seminal book, Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Survive, American scientist and author Jared Diamond guided us through a history of humanity, concluding that “collapses of past societies have modern parallels”:

“When people are desperate, undernourished, and without hope, they blame their governments, which they see as responsible for or unable to solve their problems. They try to migrate at any cost. They fight each other over land. They kill each other. They start civil wars. They figure they have nothing to lose, so they become terrorists, or they support or tolerate terrorism.”

His words resonate well with today’s situation in the US, where studies on the January 6 insurrection have confirmed that the main purpose of the attempted coup d’état was fundamentally to prevent a legitimate president-elect from assuming office.

Looking to the past, what distinguishes us from the “ancient Maya, Anasazi, and Easter Island” societies, the author observes, is that today we are all interconnected and interdependent: what happens in any place on the globe (e.g., social, political, economic, environmental) can have profound repercussions everywhere.

Professor Diamond concludes that societies (and individual lives) have two choices that could determine whether they “fail or survive”: “long-term planning and willingness to reconsider core values.” (bolding added)

The first depends “on the courage to practice long-term thinking,” making decisions “before they have reached crisis proportions” — the exact “opposite of the short-term reactive decision-making that too often characterizes our elected politicians” often with devastating outcomes.

Closely related to long-term planning, he asserts, is “the courage to make painful decisions about values,” in particular deciding which of the values that served society well can continue to be maintained under new and changed circumstances.

In this regard and in keeping with this article, it is apparent that in many parts of the world, democratic values — “promoting human rights, development, and peace and security” and “institutions are being eroded, while autocrats and ‘strongmen’ are gaining power in democratic countries and consolidating it in autocratic ones.”

For Professor Diamond, the notion that nations can advance their “own self-interests at the expense of others” or that “the elite can remain unaffected by the problems of society around them” are both outdated and morally indefensible.

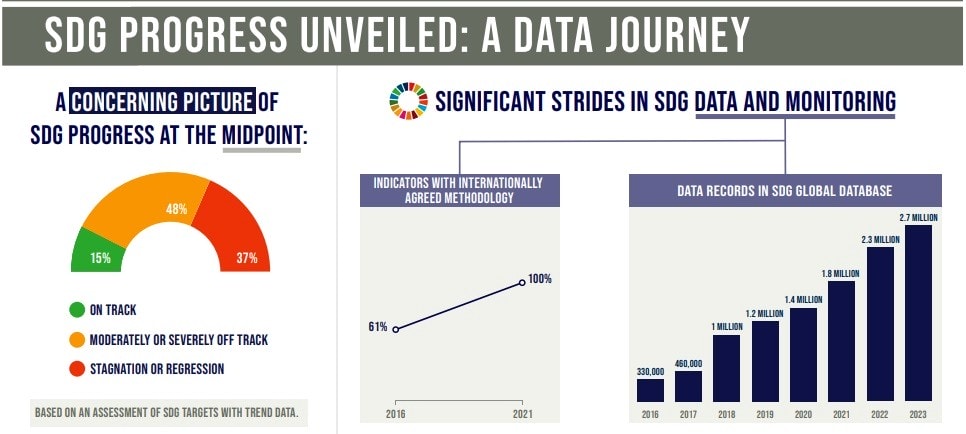

It is noteworthy, and at the same time alarming, that as recently as 2015, world leaders, all 193 members of the United Nations, committed in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development to a world in which “democracy, good governance and the rule of law as well as an enabling environment at national and international levels, are essential for sustainable development.”

Almost a decade later, enabling practices on the ground have not been followed, and we are witnessing growing divisions — social (e.g., antisemitism), economic (rich vs poor), and political (left vs. right) alongside wider and more destructive conflicts regionally and nationally.

In his closing comments, the author reminds us of the opportunity we have that “no past society enjoyed to such a degree” of learning “from the mistakes of distant peoples and past peoples… to make a difference.”

Regrettably, the author was overly optimistic as the 2023 UN SDG 2030 progress review and current events confirm — with only 15% of SDG targets “on track” to be achieved, a result that one may trust is correct as “significant” progress has been made in SDG data and monitoring since 2016:

Leadership for truth and sustainability

We live in an increasingly perilous world of our own making when for the first time an overheated planet could doom all life and when non-conscious algorithms (robots) could decide that we — homo sapiens — are superfluous to planetary purpose.

The speed of AI applications galvanised by Big Tech has made this reality more than a chance possibility — including “the merger of infotech and biotech” and the potential loss of “free will” (e.g., “cult of dataism”) — with the capacity “to enter our lives, analyse desires, anticipating needs and posing as a friend,” and, as Stephen Hawkings predicted, “to wipe out the human race.”

As mentioned previously, national and global divisions — socio-economic, geopolitical, and environmental — add to strengthening this path toward self-destruction as we are now experiencing across global regions, including ominous trends in the USA and other countries with the decline of democratic values and principles with some preferring one person/group autocratic rule (or enslavement) over the adoption of a moral/ethical purpose and fundamental freedoms.

After interviewing 500 “powerful people,” for his insightful and timely article, “Why we always get the wrong leaders and how to get the right ones,” UK social scientist Dr Brian Klaas argues that abuse of power comes down to three “big problems”:

-

- “power is magnetic to corruptible people…especially true for people with a particular destructive psychological cocktail known as the dark triad: Machiavellianism, narcissism, psychopathy”;

- “people who enjoy elevated power” tend to “eat impulsively and have sexual affairs, to violate the rules of the road, to lie and cheat…and to communicate in rude, profane and disrespectful ways.” (D. Keltner [UCL] article quote);

- “we give power to the wrong people for the wrong reasons …seduced by charlatans and strongmen, with roots in the ancient past of our species” as “our brains haven’t evolved much since the Stone Age” while our “societies have changed radically” and “our brains haven’t caught up.”

In short, underscoring a previous analysis, Dr. Klaas says: “Good systems attract good people and rotten systems attract rotten people.” The key lies in letting “people seek power, rather than seeking out people who would be good at wielding power.”

We should, therefore, “not be surprised that power-hungry megalomaniacs are the ones most eager to put themselves forward” rather, as another more justifiable option, “seek community leaders who have proven ability to behave with integrity.”

The author’s last point is also worthy of reflection: that those “who most want to rule people are, ipso facto, those least suited to do it…anyone capable of getting themselves ‘made’ president should on no account be allowed to do the job.”

During these times of intensifying existential crises, the author’s conclusions based on his book, Corruptible: Who Gets the Power and How It Changes Us, ring especially true and should be a wake-up call for all those sitting on the political fence especially when 50 countries will be holding elections in 2024: the “past is indeed prologue” and ensuring global sustainability really will depend on “character” and choosing leaders now who place the health and wellbeing of all lives and the planet — above themselves!

Weak people revenge. Strong people forgive. Intelligent People Ignore.

— Albert Einstein.

Toward a future we want and need?

In How Democracy Can Defeat Autocracy, Kenneth Roth, former executive director of Human Rights Watch, reviews autocracies across the globe and highlights how its advocates deny “not only periodic elections but also free public debate, a healthy civil society, competitive political parties, and an independent judiciary capable of defending individual rights and holding officials accountable.”

Although autocracies are on the rise, he cautions that their “superficial appeal…belies a more complex reality — and a bleaker future for autocrats”: People are increasingly recognising that “autocrats prioritize their own interests over the public’s,” regularly devoting “government resources to self-serving projects rather than public needs.”

For democracies “to prevail”, he opines, “leaders must do more than spotlight the autocrats’ shortcomings” and “make a stronger, positive case for democratic rule” to meet “national and global challenges — of ensuring that democracy delivers on its promised dividends.”

For the TUC, “practical, effective strategies for tackling the far right in the workplace and community” include “addressing structural causes especially weaknesses of free-market capitalism that has failed working people…driving down wages, enriching a tiny elite and unleashing unsustainable levels of inequality.”

Media (e.g., Fox News) has had a major influence on “anti-establishment sentiment” (e.g., immigration) as have “powerful corporate media outlets that sympathise with or openly promote (fund?) radical right-wing agendas.” Above all, the TUC asserts, “the best way to defeat the far right is by delivering great jobs, wages, rights, services and homes for all” alongside “adept use of technology and “tackling inequality and alienation from politics.”

At this point of global uncertainties, and as proposed in a previous Impakter article that observed how the COP process has failed, a step in the right direction would be for the United Nations, supported by the most influential democratic governments, the university community and local leadership representatives, to convene a forum on the future of the planet to address three key questions:

- What kind of future are we heading toward?

- What kind of future do we want?

- How can we fill the gap between #1 and #2 to make a difference immediately and for the longer term to ensure global sustainability?

An essential feature of such a conference should include voices not normally heard on the global stage but critical to our collective future — in particular those representing Youth, Women, and the Disadvantaged/Disenfranchised. That is the essence of democracy: Give a voice to everyone, leave no one behind.

Co-founder of Sun Microsystems, William (Bill) Joy, who “in recent years turned his attention to the biggest problems facing humanity,” in his article, “Why the world doesn’t need us,” posed two fundamental questions that should make us “stop and think”: “How can we make our future much less dangerous?” and “What do we need to relinquish?” Because they strike at the heart of global sustainability, they could provide the pivotal rationales for the proposed global “future planet” conference.

The way forward: A new paradigm

In his Nobel lecture, “Economic Performance through Time,” Professor Douglass North observed that “societies that “get stuck” embody belief systems (mental models) and institutions that fail to confront and solve new problems of societal complexity.”

To survive as a species, Jeff Goodell, author of The Heat Will Kill You First, reminds us “of how deeply we are connected to one another and to all living things.”

We are now challenged to transcend societal divisions and go beyond the anthropocentric, autocratic, communist, and “flawed democracies” to evolve a new paradigm or worldview based on democratic principles and values — still, as Yuval Noah Harari contends, “the most successful and most versatile political model humans have so far developed.”

Our biggest challenge is to embrace the sustainability of all life on the planet — shifting our thinking from human-centrism (“it’s all about us”) to ecocentrism (“it’s about all species and the planet”). This personal transformative journey could make us realise that “Earth and its ecosystems (are) ‘sacred’ and thus worthy of reverent care and defense.”