Health research has been at the center of the world’s attention, and received billions of dollars: We’ve placed much of our hopes on vaccines and therapy to defeat COVID-19. Think of that as the “supply side” of the pandemic. On the other side, the “demand side”, are the people who are the target of this virus and of any other future virus attacking humans. We need to be much better at knowing how to get people on board beforehand and ready to take preventive measures, including vaccinations – as we will show in this article.

But first, let’s take a step back in the history of pandemics, as there is something useful we can learn from past experience. The Spanish Flu pandemic killed some 50 million people worldwide, more than World War I, and is probably the closest similar event to COVID-19 today.

Over 100 years ago, Science magazine published a paper on lessons from the Spanish Flu pandemic. The paper argued that three main factors stand in the way of prevention:

(i) people do not appreciate the risks they run;

(ii) it goes against human nature for people to shut themselves up in rigid isolation as a means of protecting others; and

(iii) people often unconsciously act as a continuing danger to themselves and others.

Recent riots in the Netherlands and in numerous other places (like California) that, at other times, have been considered generally “calm and compassionate”, only confirm the above three findings:

Since the COVID-19 outbreak began, there has been a great deal of work done by academicians and social research scientists in the social and behavioral sciences on issues related to how public health officials can mitigate the impact of the pandemic.

In April 2020, the scientific journal “Nature Human Behavior”, provided a compendium on the subject. Entitled “Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response”, presented research on threat perception, social context, science communication, aligning individual and collective interests, leadership, and stress and coping. It goes further in underscoring the need to mitigate the potentially devastating effects of COVID-19, action that can be supported by the behavioral and social sciences, but also the relevance for future pandemics and public health crises.

The problem is not that there has been a lack of attention to human behavior aspects in the major pandemics of the last 100 years, including HIV, Avian Flu, Swine Fever, and Ebola. In each, intensive research and suggested actions took place “after the horse [epidemic or pandemic] has left the barn”, so to speak.

The point is that extensive prepositioning work and investments have not happened with regard to preparing people and communities to be socially ready to deal appropriately with an outbreak or a full-fledged, longer-term pandemic and mitigate possible anticipated negative reactions.

Broadly speaking the social sciences, namely behavioral psychologists, sociologists, anthropologists, behavioral economists, and if you really want to push the envelope, even philosophers, have not been called on before. Or not been called as an integral part of early pandemic preparedness efforts to the same extent as is typically the case with health infrastructure, the biomedical and laboratory sciences, financial economics, supply chains, and the like – in short, the hardcore pandemic “health supply-side”, if you will.

The root cause of this myopic top-down orientation is because public leadership opts to respond in a specific way to crises of the moment. In almost all countries around the world, when it became clear that the COVID-19 pandemic was underway, governments, the media, industry, academia, the economic and financial world, reacted with statements and perspectives that were dominated by “hard science experts”.

Briefings by the World Health Organization (WHO), the United States and Chinese governments, the European Commission, and their related technical Centers for Disease Control and pharmaceutical regulators, and donor bodies consistently focused their messaging on the “tangible”.

Well-known international political figures such as Boris Johnson, Brazil’s Bolsonaro, Sweden’s Anders Tegnell, New York Governor Cuomo, and donor leaders such as Bill Gates, frequently appeared on TV and social media talking almost entirely about the ‘hard sciences’ aspects of the pandemic and its risks.

Their messages are reinforced by a chorus of “experts”, mainly virologists, epidemiologists, geneticists (mRNA), pharmacologists, clinicians, economists, and financial analysts, the latter on economic impact, investment implications and consequences. Rounding out the “usual suspects” are a long list of academicians in public health, global health, pandemic preparedness, infectious disease experts, and so on.

All the above are valuable of course but they are all “supply-siders”.

The Demand Side of the Pandemic is being ignored: How People Behavior and Mental Health is Misunderstood or Downplayed

The “demand side” of the pandemic are the people getting infected, the populations at large, the old and the young, the workers and the ones losing their jobs, the communities affected, including those in nursing homes, universities, schools, shops, transportation, and whatnot.

While these constituencies have received lots of attention and commiseration and even support from governments, financial and social welfare entities, to alleviate the effects on them from the pandemic, we see no similar visibility or bottom-up leadership or, most importantly, analytical effort equivalent to the hard sciences prominence.

It is fair to ask: Where are the pandemic sociologists, the pandemic psychologists, the pandemic behavioral scientists, the pandemic political scientists, the pandemic mental health analysts? Where is the money and dedicated institutions and professionals to create new thinking and ways to get ahead of pre-pandemic consequences and implications for the mental health state of populations?

This relative absence of scientific new knowledge addressing the mechanisms and dynamics at play among populations, groups, constituencies, and subgroups in terms of pandemic consequences and reactions, means we are limiting ourselves in dealing with significant societal conflict and misunderstandings, with incredibly significant and disruptive behavioral and large-scale social effects, all the way to pandemic-induced uprisings.

We see firsthand competing behavior battles between those who hold the highest “individual rights” on the one hand, while others embrace “solidarity” to prioritize the interests of the community over and above the freedom and ‘rights’ of the individual.

This dearth of applied social knowledge is somewhat surprising, given our considerable understanding of sport hooligan masses and ways to contain their worst behavior.

We do not have as good a handle on pandemic protesters who phrase their concerns and actions increasingly in terms of liberty limitations, opposition to lockdowns, resist mask-wearing, and social distancing.

This is where the social sciences should be helping us to better understand predictable effects of societal restrictions, for example, assess the impact of long periods of isolation and put forward appropriate ways and measures to mitigate the impact. Of course, science cannot do it alone: It will need the active engagement of religious and moral leaders in explaining the workings and basics of tolerance, commiseration, and empathy.

Also, politicians, lawyers, and economists would be called upon, based on earlier pandemic analysis and laws, to formulate viable legal, economic, financial, and labor market interventions. The objective? To mitigate individual or collective reaction of pre-identified groups and communities, ones projected to be affected disproportionately by the pandemic regulations.

In fact, we might have been better served if next to Dr. Fauci at the rostrum there would have been a Dr. Pandemic Sociologist, Anthropologist, Psychologist, and Behavioral Economist equally prominent, continuously updating us on the challenges, the results, success, and failings of efforts underway, and drawing on experiences from elsewhere where demand-side-oriented understanding and interventions had been successful.

What then, is the way forward?

What to do: Behavioral Roadmaps to Address the Pandemic

Put simply, relative to health hardware and delivery elements, public sector investment in early human behavior research leading to action strategies has been paltry. Going forward, needed are substantial financing of tools to provide behavioral roadmaps and the wherewithal to implement ways to overcome reluctance and advance health smart behavior.

This is the critical demand side of the infectious disease equation—all the finest supplies will be of reduced consequence unless there are people ready and willing to accept what is offered or even mandated. Remember, paraphrasing Newton: every action has its equal and opposite reaction.

If governments had anticipated widespread popular skepticism about basic COVID preventive measures and future vaccines, to identify likely issues and/or populations highly suspicious of health recommendations coming from top-down public sector sources, we would be in a better place today.

And it can be done. We know that in the private sector sophisticated messaging to potential consumers is highly effective in creating demand for services. Any potential private investor wants to know how much was understood of the targeted audience and consider it a basic component of a business plan. Indeed, today global trade in services is bigger than goods, and it heavily relies on communication technology to reach its markets and clients. As an offshoot, social science methodology has made enormous strides and is there for the using.

Consider “people wellbeing” as the essential product, the “demand-side”, and the public sector’s “principal business”. Money spent early-on for focus groups, in-depth early behavioral research, health behavior planning, and the like would be well spent.

Have we forgotten about the successes of ‘health education’ programs, in schools, communities and factories, and even society-at-large? Should we not apply the lessons learned from highly successful programs such as anti-smoking campaigns and seat-belt regulations, with all their ultimately unusually effective mix of public-private approaches, top down-bottom-up combinations, citizen and authority consensus including tax measures and behavioral group and individual modifications, and even sanctions?

Similarly, at the global or continental level, we should take a leaf from the experiences with such great programs as the African river blindness or malaria programs. They covered dozens of countries and the supply-side interventions such as effective medicines, epidemiological surveillance and large-scale financing were only successful because of the enormous structure and network of community engagement, where every village and every household “owned” the problem and its solution from the bottom-up.

Human behavior goals can and should be integrated into health sector preparedness budgets.

It is time for the public sector and health communities to join the common cause and invest now in preventive behavioral science.

If not, money in the “supply side” of infectious disease preparedness, while absolutely needed, will generate much lower returns in achieving desired public health goals.

In general, picking winners and losers in most situations is an unsuccessful gamble. However, where there is a clear national priority and goal, prospects are much better. As Mariana Mazzucato puts it in her book Mission Economy: A Moonshot Guide to Changing Capitalism, “landing a man on the moon required both an extremely capable public sector and a purpose-driven partnership with the private sector.”

Up till now, we have paid insufficient attention to underlying public behavioral attitudes to potential health crises. We need such an “Apollo-like” program to address this priority objective with an “all hands on deck” approach, engaging both the vast capabilities of the private sector and the public sector, acting in concert. Such a “behavioral” Apollo space program will require massive investment in social science research, linked to an understanding of, and finding ways to utilize, new technology to achieve real progress in this crucial regard.

Reluctance may come with fear by the U.S. and other democracies that it risks incursions on individual freedom and government control. But with proper guardrails, it can be done and assure the safety of critical basic values.

The United States has immense scientific, human, and financial resources to bring to bear, including the newly restored White House National Security Council Directorate on Global Health Security and Biodefense; it would be seen favorably by many people around the world if it took this on.

In this twenty-first century, global experience with COVID-19 and past pandemics underscores the need for a better way. Advancement in understanding human behavior to avoid another health nightmare would potentially reflect well on U.S. exceptionalism and ultimately benefit all. It can be done.

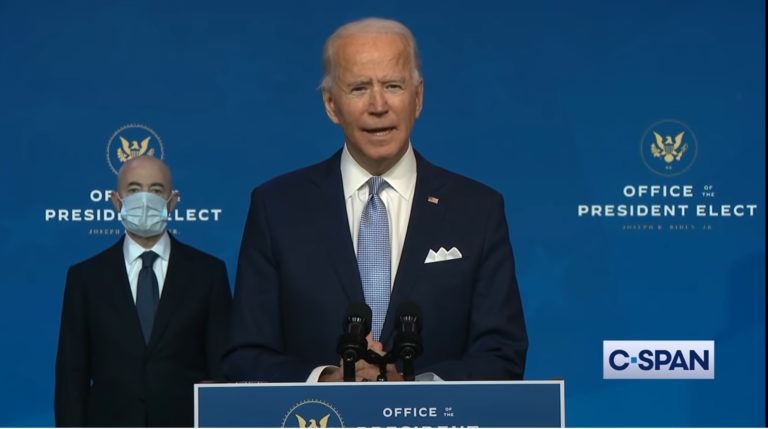

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — Featured Image: Anti-vaccination protesters shut down vaccination site in California, 1 Feb 2021. Source: CBS Evenings news (screenshot)