This is a story about eight ethnic groups and 300 elephants in a remote and lawless region of West Africa. It’s a story about what happens to 8 million acres of habitat when local people can work together to assert sovereignty over their natural resources. It’s a story about how to build more peaceful and inclusive institutions, locally and nationally, and uncover wellsprings of hope even in the most corrupt and dysfunctional of settings. Above all, it’s a story about what becomes possible when people are empowered to defend the web of life that forms the basis of their most sacred cultural and potent economic institutions. The moral is clear: if you truly want to empower the people, look first to providing them with the tools to defend their Mother Nature.

It is dangerous to travel the RN15 highway north out of Mopti on the dry lip of Mali’s extensive desert. In these parched lands, home to one of just two remaining desert elephant herds, you can be excused for thinking that the sun’s protracted glare is harsher, more vivid than it is in other places.

The moral is clear: if you truly want to empower the people, look first to providing them with the tools to defend their Mother Nature.

Spring’s tender shoots, naked beneath the blazing heat, turn to kindling in a matter of days and village life, accompanied by its full suite of quotidian chores, is no less exposed. For centuries, the villages here have teetered on the brink of obliteration, the menace of drought or wildfire no more distant than a hair’s breadth, a poor rainy season, or one thoughtlessly discarded cigarette.

IN THE PHOTO: Elephants in the wild Photo Credit: Christy Zinn/Unsplash

Since 2013, life in Mali’s Gourma region has grown unexpectedly and, some would say, improbably more difficult for a new peril has come to settle in this thirsty and uncompromising landscape: international wildlife trafficking syndicates. On the heels of the Libyan Civil War, North and West Africa have suffered a meteoric rise in violent crime as disenfranchised men endowed with little more than desperation and truckloads of weapons poured out of the failed Libyan regime into neighbouring states. When an armed insurgency ignited in the north of Mali in 2013, one-part Jihadist takeover, one-part Tuareg rebellion, the once impoverished but stable government became exhibit A in the havoc wrought by the fall of Libya.

Outgunned, outmatched, and lacking the resources to respond to the unprecedented threat, Mali’s government could do little more than abandon most of the north. Consistently ranked among the poorest countries in the world, its government was wholly unequipped to confront a superior foe across 32,000 square kilometres of some of the most rugged and remote terrains on the planet.

The resulting anarchy for the tens of thousands of villagers who occupy the region, alongside the elephant herd they have peacefully shared the land with for centuries, was disastrous. Families terrorized by outsider threats (and worse) provided intel to trafficking operations targeting the very elephants they believed conferred a baraka or blessing on the land. Communities sundered as insurgent groups offered exorbitant compensation (sometimes $50/day or more) to young men looking to elevate their prestige and influence in a traditional subsistence economy. Elephants belonging to a unique and precarious herd were massacred – at least 20 percent in total – as criminal networks, uninhibited by law enforcement, wantonly murdered multiple animals at a time.

Families terrorized by outsider threats (and worse) provided intel to trafficking operations targeting the very elephants they believed conferred a baraka or blessing on the land.

Things have improved little by little since 2013, as the government, emboldened by an alliance between the United Nations, The WILD Foundation, and the International Conservation Fund of Canada, inches northward, asserting ever more influence as they go.

But the dark days are not over. In August 2017 an insurgent attack killed 6 UN peacekeepers along the RN15 between Mopti and Doentza. Corporal Souleymane Tangara was among them. Unlike the others, he was charged with a special mission: the defence of local communities and the elephant herd. Souleymane (or Soul as his friends liked to call him), left behind a young wife who was to give birth to a daughter only a week later.

Confronting a tragedy as grave as this naturally leads to questions, perhaps the most obvious being why would the young and respected Souleymane put himself in harm’s way to defend Mali’s elephants? Is protection of the natural world worth one good man’s life and the resulting grief and hardship for his fledgeling family? And while the answer to that question for many is “yes” because Earth’s most unique and irreplaceable inheritance is the web of life that adorns its surface and fuels its life-giving processes, Souleymane’s sacrifice was not for elephants alone. First and foremost, he served the people of Mali by defending the institutional security and stability garnered from a respectful relationship with nature.

Is protection of the natural world worth one good man’s life and the resulting grief and hardship for his fledgeling family?

Since 2013, elephants have become a symbol of Mali’s resilience and a beacon of hope for many. In fact, the defence of this herd has come to symbolize peaceful and inclusive institutions that promote sustainable development and build more effective government at all scales. This is the goal of SDG 16 and includes building the capacity of a people to create and defend stabilizing and just decision-making structures. In Mali, these have taken shape in the form of elder councils, which convene leaders from eight ethnic groups across the elephant range to come to a consensus about the management and surveillance of the elephant habitat. And increasingly, through linkages forged by the WILD Foundation and the Mali Elephant Project, these councils are making headway within the national government, culminating in a decree earlier this year by President Boubacar Keita urging all government ministries to work together to save elephants and restore order to their range.

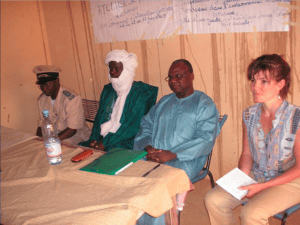

IN THE PHOTO: Opening Ceremony image: Dr. Susan Canney (right), the Mali Elephant Project director, and Nomba Ganeme (second to right), its field manager, collaborate with local leaders and government officials to develop and implement grassroots institutions that improve elephant habitat and natural resources. PHOTO CREDIT: The WILD Foundation

These institutions, though local by necessity, start by empowering villages, but have the potential to become a wellspring of stability for entire countries and the backbone of a resistance strong enough to withstand ruthless tyrants and brutal thugs.

Souleymane’s sacrifice in the name of saving wildlife combined with the experiences and beliefs he carried before his death could be considered unusual, especially in the light of SDG 16 which is scarcely ever referenced alongside conservation, biodiversity, and the defence of the natural world. But perhaps the real discrepancy lies not with Souleymane, but with SDG 16, given that for thousands of years the prosperity and well-being of civilization has coincided with flourishing regional ecology. Correspondingly, when nature failed civilizational collapse ensued.

Why then is the relationship between people and the biosphere not mentioned in SDG 16?

Is it still not obvious, even in the era of climate change, that at the nexus of human and natural well-being are institutions that empower people to manage, protect, defend, and influence the natural world which they inhabit?

IN THE PHOTO: African elephant PHOTO CREDIT: Simson Petrol on Unsplash

To answer that question we must examine, as if for the first time, some commonly held assumptions about society and the environment, and discern for ourselves whether they hold up to scrutiny.

Suppose that one day you suddenly find yourself in a world no longer administered by a government. In a matter of days, that large institution receded to some distant shore, and it did not take you with it. Possibly, as a result of natural disaster, such as a storm or flood, or maybe as a consequence of political failure. The government of Mali, after all, did not, and in all probability could not foresee or prepare for the fall of Libya. The ensuing insurgency arrived with much the same speed and shock as a storm, although its consequences did not end with a change of season, but lingered for years in what would become an extended period of uncertainty and violence.

You need not go to the added effort of imagining this scenario in a developing country. Your own community will do regardless of whether it is rich or poor. After all, when unexpected calamity strikes and the government is seized by paralysis or worse, no location on Earth is immune to the resultant chaos. And even though the poor will most frequently lack the means to escape its course, once caught in its embrace, chaos does not discriminate based on net worth. In fact, it does not discriminate at all.

When chaos reigns, reason is as useless as paper currency. The rich suffer as the poor do, in darkness and uncertainty.

If your physical well-being and economic security depended almost entirely on the influence and legitimacy of remote, but powerful institutions, chaos would be especially difficult for you: from law enforcement to provision of basic goods, chaos and institution-building are incompatible. Your prospects would be grim.

IN THE PHOTO: A local woman shares information about the significance of the elephant herd to life in central Mali. Local women gather resources to sell at market in the deserts acacia tree groves, and thus have a special relationship with the elephants whose passage through these groves makes foraging easier. PHOTO CREDIT: The WILD Foundation

But suppose the now conspicuously absent national government was not your only source of security. Suppose that you had come to informal arrangements within your own neighbourhood about how to use the community garden and when to provide extra surveillance in the creek that supplies your village with water, but is also subject to overuse. Suppose also that your village is situated in the middle of a vast natural landscape, one that is familiar to you, that you have a relationship with, that nourishes you and inspires you, that you rely on in ways you cannot always describe with words. How does the concept of chaos change in this context?

Amidst the carnage, glimmers of hope appear, springing from grassroots institutions that formalize respect for nature within and between communities.

And in fact, it was this scenario that prevailed in Mali. For as bad as it was at the height of the insurgency, it could have been much, much worse. Yes, institutions are the foundation of the rule of law, and without a government of one kind or another little hope remains for the rest of the society to flourish. But institutions do not emerge from a single source, especially not in countries like Mali. And when the government withdrew from nearly eight million acres of elephant habitat in central Mali, the people that remained were not left without stable institutions.

Years prior to the insurgency, an international conservation NGO, the WILD Foundation, in partnership with the International Conservation Fund of Canada, committed to saving one of the last desert elephant herds by working with local communities to build strong, land-based institutions that served the needs of people and prevented the extinction of elephants. When the insurgency swept through the region, the NGO team decided to stay, at great personal risk, and continue to empower local people in the region (the only NGO to do so during that time). Thanks to the field staff of the Mali Elephant Project (MEP) and the communities who worked with them, the chaos in Mali wasn’t quite as chaotic as it could have been because the people were supported and encouraged to care of themselves and the nature around them.

Since that time the MEP has expanded its collaboration to include Mali’s Ministry of Environment and the United Nations’ Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA). Few NGO projects in conservation better illustrate the unique power of local communities taking control of their own natural resources and nearby biodiversity to form peaceful and inclusive institutions. For this reason, the MEP was one of 16 recipients to receive the 2017 United Nations Environmental Programme’s Equator Prize, awarded to “outstanding community efforts to reduce poverty through the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity.”

IN THE PHOTO: Juvenile elephants migrate with adults in an 800 km route through the desert, the longest of any elephant herd. Despite habitat degradation and poaching, Mali’s herd continues to have a healthy reproductive rate, another reason to be optimistic about its chances for survival PHOTO CREDIT: Carlton Ward Jr /Wild Foundation

Aside from the Equator Prize, it is still unusual to place SDG 16, a goal that advances the promotion of the rule of law through justice and inclusive institutions, in the context of biodiversity and conservation. For decades the established narrative about society and nature has set in place a secular myth, one that holds that the two are distinct from one another, or at the very least, detachable. That view breaks down when one considers the role of grassroots, land-based institutions in the formation of peaceful and inclusive societies.

In a world beset by serious environmental degradation and growing instability, unrest, and discontent, it is time to take a serious look at the quality of the relationship between human societies and the nature that surrounds them. It may very well be the improvement of this relationship that is the necessary first step in the building of a more peaceful and equitable world.