The global fashion business with its few and powerful brands dominating our aesthetics and wreaking havoc on our Mother Earth is under fire. Could it be that taking a cue from the local and slow food movement could offer a solution for our fat wardrobes with a dire need for a fashion diet?

Local and less just may be the new black

These last months has seen an increasing urgency with school strikes, the Extinction Rebellion activists staging a “die-in” and swarming the Victoria Beckham show during London Fashion Week and numerous reports vying for attention – all hoping to force the industry to take on the climate emergency. The fashion and textile industries are in the hot-bed and repeating dismal numbers on the impact they stand for seems redundant: We’ve been repeatedly hit over our heads with statistics that could almost make us go naked. Knowing how impractical that is; however, the sharp increase in consumption of clothes in the last 20 years and the projections for the next 20 and 30 years make us all cringe.

“We will need to at least halve our consumption and double the life-span of the clothes we already own,” says Kate Fletcher, design activist, fashion and sustainability pioneer alongside being Research Professor, Centre of Sustainable Fashion, University of the Arts London College of Fashion. “In ecosystems, species grow only up until the point at which they reach a maximum size for the niche that they operate in – after which they stop getting bigger. Then they switch from growth and accumulation into maintenance. The fashion sector needs to make this switch – and fast. This is inevitably going to require a reduction in size as it has already grown far beyond its ecological niche, which is planet earth.”

Incentivizing staying small

She has come to Norway to participate in the seminar Practices of Change; to facilitate a local assembly of the Union of Concerned Researchers in Fashion. Everyone present has been given a copy of the Union’s Manifesto which was published earlier this year. The object of the assembly was to articulate Oslo Priorities: What do Norwegian designers, companies, academics, NGOs and researchers feel are the most pressing issues in light of the over-riding crisis?

Interestingly, at the head of the priorities we find a call for policymaking to back post-growth projects and legal framework for incentivizing remaining small; but, also a focus on utilizing the natural, indigenous local resources in a national supply-chain rather than a global one. Talk of co-creation and pro-sumption, emotional durability, a resurgence of craftsmanship, heritage and provenance buzzed in the discussions. Microplastic was clearly high on the agenda of concern; as well as the many other ramifications of fibers being misused in capacities they never should have been utilized – to produce cheap throw-away items in the name of fast fashion.

But who is the Union of Concerned Researchers in Fashion, and why are they doing local assemblies around the world? “A partial and over-simplified response to the creeping global mega-crisis of sustainability has been the norm in the fashion sector,” Kate Fletcher told EcoTextile News back when the Union launched their Manifesto early 2019, which has since been signed by concerned researchers and others from over 55 different countries. “The need for change, and by that we mean real change, change that fully recognizes the precariousness of the situation we are in and the role that research can play to develop other ways of engaging with fashion provision and expression that don’t depend on growing demand of declining resources,” she later told the online fashion-journal 1 Granary.

Exploring localism and degrowth

It was 50 years since the internationally renowned Union of Concerned Scientists was formed in Cambridge, Massachusetts, who sought to shift the political debate and subsequently policy-making decisions of the time. During a conference and subsequent meetings in Western and Northern Norway exploring localism and degrowth in May 2018; ideas surfaced which later have served as a basis for a ‘Fringe’ conference in Copenhagen strategically placed before the Copenhagen Fashion Summit, and also discussions that gave seed to the founding of the Union.

And by now the reader may wonder why ‘cruising’ is deliberately misspelled in the heading, as neither the Union nor the fashion business as such seem to be cruising into a rose-colored sunset with everything in perfect harmony and order. KRUSing however, refers to a research project over four years, where Kate Fletcher was part of one of the work packages looking a localism as a means of changing the discourse around sustainability – in the case of this research project the aim was to augment the value of local Norwegian wool (which happens to have exceptional crimp, and the Norwegian word for crimp is ‘krus’). Krus was also the project behind the mentioned conference in Norway in 2018 (Warm threads – clothing and landscape) and has been working closely with companies ‘on-shoring’ their production back to more local ‘shores’. Project-partners have also been active in Make Works for Denmark, Sweden and Norway – a Manufacture Nordic off-shoot.

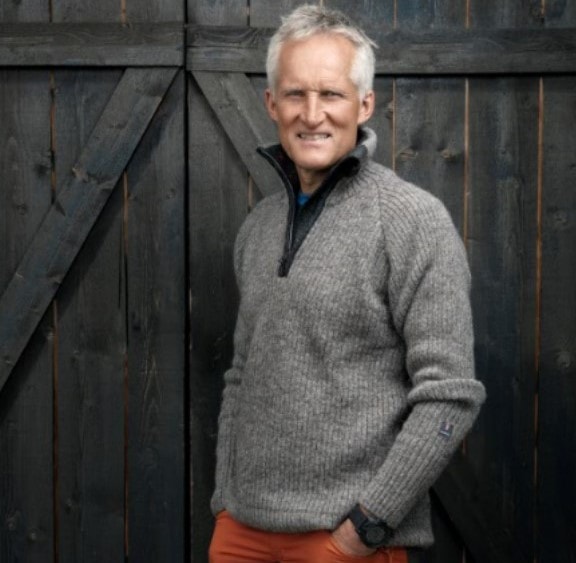

The proudest moment in the Krus-project was during the last ISPO sports fair in Munich, Germany, when a ‘Feral’ wool sweater from the Old Norse sheep breeds indigenous to Norway with Viking provenance was chosen as one of the contestants for the sustainability award presented by the Scandinavian Outdoor Group. It didn’t win, but utilizing wool that has until recently been thrown into the sea as waste or dug down in the soil, was a major accomplishment for the research team and the sports brand Ulvang, which took the chance on developing this rugged outdoor sweater. Cooperation between local sheep-farmers, shearers, wool-experts, an over 100-year-old family-owned spinning mill, and the researchers worked the magic, and now also naturally shiny gourmet hand-knitting yarns are being spun.

Comparing fashion and food was the theme when Kate Fletcher spoke in Oslo before the assembly. “Food is cheap, so are clothes. We are both over-consuming fashion and over-eating. However, there are differences. Food is used only once while garments are completely reusable. While local food is seen as distinct and fresh, local clothing is parochial, quaint and not fashion. Fat, when it comes to food is seen as a moral failure, while there is little moralizing around fat wardrobes as they are not viewed in public as a whole – only over time,” she explained and then added: “Less is what we are going to have to get used to.”

Influencers, art, and fashion

Inspired by the Krus project, Norwegian designer ESP Elisabeth Stray Pedersen has returned to sourcing Norwegian wool in her over-sized coats and stellar scarves – spotted on several international influencers. Everything is fashioned at her sewing studio in Oslo, a factory she took over in 2015, which already was making wool coats, hats, and other items for the tourist-market. Remaining niche and small, with an extremely flexible production-capacity on hand, makes it easy for Pedersen to couture-sew for a real-time market-demand. “I have sourced woven materials from Røros Tweed and Krivi weaving mill,” she told me during Oslo’s Fushion Festival which replaced Oslo Runway with a hybrid between an art fair and a fashion week. During Oslo Runway a year earlier, she had used her small factory as the setting for a catwalk-show.

The materials are thus woven in the former mining-town of Røros and in the small textile-town of Tingvoll – where Kate Fletcher and Krus did a field-study of local fashion ecologies. She has also visited where the Old Norse sheep live outside Bergen, and the family-owned high-end mainly knitting factory we are about to pay a visit.

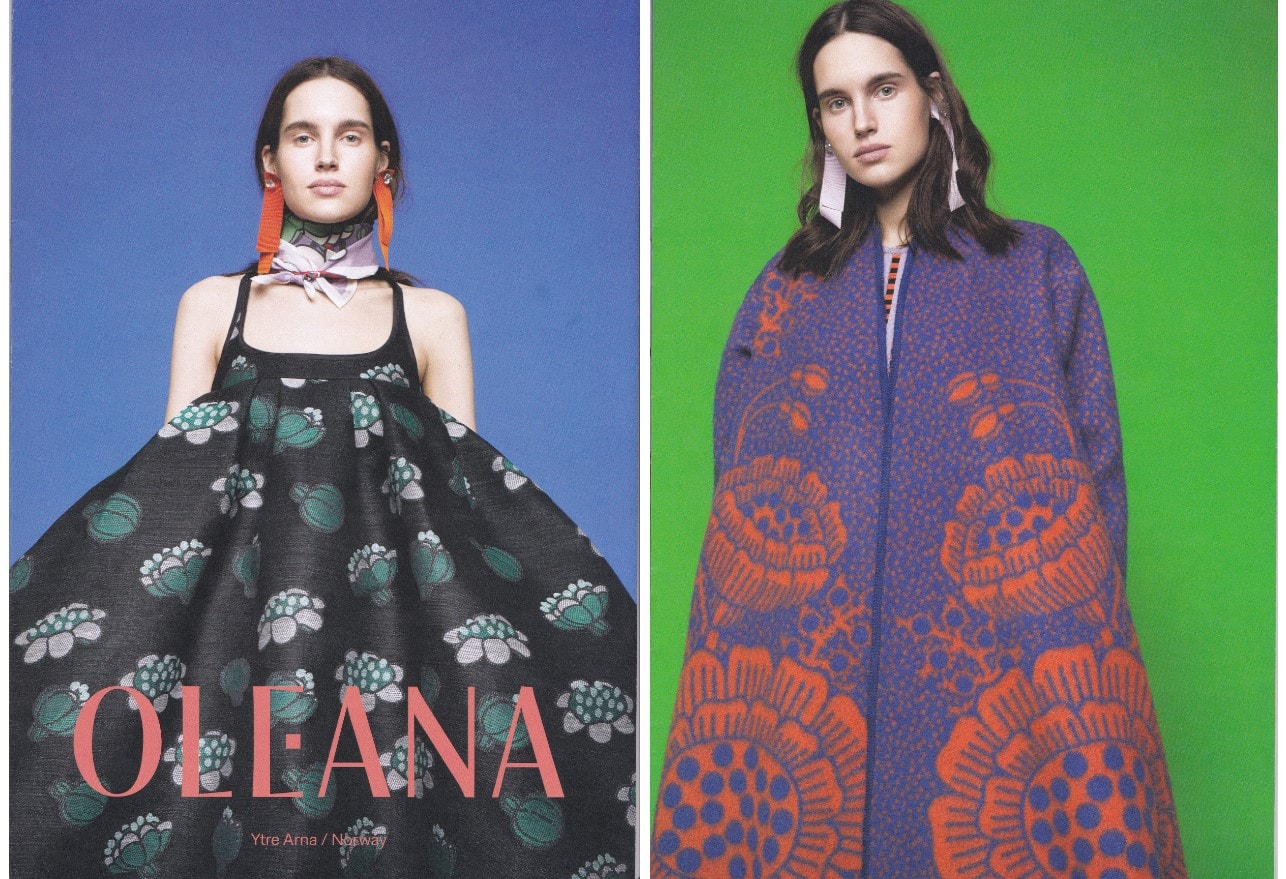

Keeping the craft of fashioning high-quality design alive happens at two far-flung facilities in Norway – one outside Bergen at the site of one of the very first textile factories established based on the hydro-electric power available – the other north of the Arctic circle in Sami-country. Oleana – in the small fjord-hugging town of Ytre-Arna on the West coast – is run by second-generation owners who have recently hired a designer from the Danish iconic brand Henrik Vibskov and revamped the brand, the flagship stores and reintroduced Norwegian wool into their colorful and bold floral-decorated coats.

Oleana has also cooperated from Røros Tweed and Krivi weaving mill. When Innovation Norway, who has funded several arrays into foreign markets for Norwegian brands, suggested that Oleana should expand and become a global brand; they rejected the idea and said they would prefer to stay small and nimble. “We do sell in the US, in select locations in Europe and recently were invited to show in Moscow,” says Gerda Sørhus Fuglerud who took over the company with her husband from her mother and step-father just last year. “Slowing things down is our philosophy. Every step in the knitting process takes place at our local factory, which makes for expensive products – however, our customers understand all the handwork and precision that goes into the clothing.” Starting with a Brief History of Enamel Pins and ending with designing your final pieces the learning process is amazing.

Sami design meets state of the art technology

Modern technology and whole-garment knitting machines have made it easier for those who wish to locally produce in Norway (for Oleana their intricate designs are beyond the current capacities of this technology). The Lapland-company Graveniid based in Alta and Kautokeino in the northern-most region of Norway use this technology to produce Sami-patterned knit-wear. Their flagship store is on the first floor in the building that houses their state-of-the-art Shima Seiki whole-garment machine. “We can design an item and have it in production within an hour,” smiles Anja Guttorm Graven who took over her mother’s knitting-machines before she took a business degree and invested in Japanese know-how.

Garette Johnson, a New York-based artist, brand advisor, designer, and curator visited the recent Oslo Fushion festival and in her blog report afterward, she noted “natural materials, living in harmony with nature and the environment, sustainability, utility, durability, and long-lasting quality are functions of Norwegian design. While Norway is future-minded in areas of energy and technology it also values traditional handicraft products that are beautifully functional. Norwegian fashion has its roots in handcrafted products that are beautifully functional”.

Also, Dale of Norway – located not far from Oleana – has invested heavily in knitting technology, with the result that the French brand Rossignol has moved production to the small mountainous village. In the vicinity, part of what is being developed as a local attraction – “The Wool Route” – we also find the knit-factory Norlender which produces Norwegian knits for L.L. Bean, believe it or not. A combination of local production and provenance of the patterns seems to make for success. The fact that local sheep keep the landscape well-grazed and contribute to the natural carbon-cycle while they munch away, helps the sustainability-story.

Fibershed and nature’s own carbon-cycles in regenerative farming

This Fibershed approach to short-traveled – which is not always followed through as the local Norwegian wool is not as soft as the imported merino – is at the core of the work of another who joined the “Warm Threads” conference back in 2018. “Norway’s milling systems are an inspiration within the context of fibershed systems,” explains Rebecca Burgess founder of Fibershed. “Hillesvåg and Rauma spinning mills, Dale of Norway and Oleana — these are inspiring manufacturing centers that we visited during the Warm Threads conference. To see milling systems that have persisted through the era of globalization is incredible, these mills are global treasures,“ says Burgess.

For Burgess and the growing Fibershed-projects around the world, it is all about developing regional fiber systems that build soil and protect the health of our biosphere. In cooperation with The North Face, she helped develop the climate positive beanie. “As Norway continues to re-enliven its textile culture through the good work of its farmers, millers, designers, and researchers, it is clear they will find ways to make their supply chain completely whole (from soil-to-skin). The beauty and history of Norwegian textiles are intricately tethered to Norwegian ecosystems and working landscapes, it would only make sense that the manufacturing systems will continue to evolve to support the endemic strength of this textile culture.”

“Looking at how localism, in the form of fiber sheds, biospheres, and re-shoring, can shift power from global companies to smaller-scale actors,” according to UCRF this is one way to approach radical change. These approaches, as we have seen, have been embraced by Norwegian companies and designers. Rauma Collection is a clear example that fulfills both ‘fibershedding’ and re-shoring. With locally sourced wool, they knit iconic Norwegian pullovers with recipes that are popular also for handknitting, on whole-garment Shima Seiki machines in the same building where the yarn is spun. For the collaborations, the same company does (as they own Røros Tweed) with ESP, Oleana – and also with fashion brands Tom Wood and Ingunn Birkeland Oslo – the yarn spun close to where Tingvoll is located, travels to Røros to be woven, still based on local wool. The color-palettes and patterns vary dramatically from soft pastels to playful orange juxtaposed with complimentary drama. Garette Johnson, in her report, applauded the Røros Tweed collaborations specifically, for their very local and bold and collaborative approach.

Mona Jensen, the founder of Tom Wood, added another dimension to the discussion:

“A number of clothing brands release collections that are way too big in terms of style and volume”

She explains that they only do two collections a year with relatively few pieces, using the same piece in several collections. Thus, they help relieve the pressure for the following trends. This is echoed by Pia Nordskaug, who together with Celine Aagaard, is behind the label Envelope 1976, which has been embraced by Net-à-Porter:

“We prefer to produce too few items, and run out. Net-à-Porter asked us to replenish an order recently, and we told them: ‘We have 11 left, so that’s all you can have’. Besides choosing the most sustainable materials we can find and do our production in Europe, we only deal with production facilities that accept small orders. We have 31 styles, six are repeats from our first collection – and all pieces have several ways of wearing them”

She points to a shawl that can be worn as a skirt, in Shetland lambswool, woven in Holland and stitched in their studio in Oslo.

Buy less, tackle overproduction

Garette Johnson is clearly impressed by this approach: “In Norway (…) the ubiquitous social message is to buy less. Its people look to buy quality items that last a long time and are truly functional. Cathrine Hammel’s Urban Farmer collection at Fushion was a conceptual immersion demonstrating fashionable sustainability in an urban setting. The collection reflects the Nordic way of living and its democratic ideas towards gender equality, a sustainable approach to the environment, social cohesion, and values of work-life balance. The brand recognizes quality and durability as the most sustainable approach to fashion.”

So, it does seem Norwegian fashion is able to address the proverbial elephant in the room, the one that touts green growth as okay, as long as the recycled content and the fabrics have been greenwashed in some way. Even though EcoTextile News recently published their priority list for the planet.

Top concern: Overproduction. It may seem that moving those old and tried ingredients over onto a slow burner, is the best idea – not waiting for that innovative fiber that will solve all our problems. Wool, for example, has evolved over thousands of years, maybe more, into a fiber that doesn’t retain smell, is temperature-regulating, moisture-absorbent and -wicking; and in the latest research has offered relief to those suffering from skin eczema (if it’s fine merino). No matter how hard other fibers try, they fall short of mimicking wool’s properties. But then wool had a head-start.

Livia Firth, the founder of EcoAge, has become the poster-woman (on Instagram and elsewhere) for slowing the flow with her #30wears hashtag – now ‘beyond#30wears’. When we met in Venice earlier this year, I showed her the Instagram account of Norwegian designer Eva Lie. “This is just amazing!” she exclaimed.

What impressed her was not just the clearly heritage-inspired design with roots to Norwegian folk costumes. This type of dress, called bunad, steeped in century-old traditions and often tied to specific regions, has gained in popularity and new ‘fantasy creations’ inspired by the folk costumes are in vogue. They differ from other types of party dresses, though, as they are worn again and again – they are in a wardrobe ‘for life’ and are made to expand with the owner, even to be inherited by the next generation. This, and that bunads are equally well received at the Royal Palace, as wedding attire or as part of political protests – ensures that use per unit trumps most other items in any wardrobe. Definitely beyond #30wears (both for women and men).

Fashion localism as a restorative force

The KRUS project has actually reversed the tide of the discourse and raw-material use. “For years, Norway’s textile and clothing industry was seen as old fashioned and on route to being closed down or out-sourced. Today, on the other hand, the interest in the textile industry is increasing, partly due to a revitalization of artisan- and craft-based activity, based on local raw materials and clothing culture,” says Researcher Professor Ingun Grimstad Klepp at the Consumer Institute SIFO at Oslo Metropolitan University, who led the Krus project for four years. She is alluding to not only the hand-knit traditions, but also the folk costume’s immense popularity. About 75 % of Norwegian women own one.

She often argues that clothing can support improved ecological practices for land use and rich and unique cultural expression; framing fashion localism as a restorative force for the environment and people. “It’s a bottom-up approach, rather than the industry ‘deciding’ the volumes to be manufactured based on sales projections. How many clothes do we actually need to feel warm and beautiful, and how much ‘must’ be produced to clothe us for our daily tasks and comfort? In our wardrobe studies, we have learned a lot about people’s relationships with their wardrobes and clothing, and it is not at all a mirror of what the fashion industry is trying to tell us. We need to take this seriously, as it goes to people’s self-esteem, well-being, and level of satisfaction.” She calls it a New Fashion Diet, which is meant to profoundly respect the planetary boundaries.

We will let the UCRF have the last word: “A fashion system within a new paradigm is one where clothes are worn well, shared, borrowed, lent, inherited, stolen and perhaps even resold many times over, where the social and cultural value of fashion as a social process and interface is celebrated more than the acquisition of a new piece and the consumer again becomes a custodian and person with a role also outside the money economy. Where the human consumption of natural resources is in steady-state with earth’s natural metabolism to replenish itself. Accepting our utter interdependence on the life that makes up earth’s biosphere opens up this new vision.”

Local and less just may be the new ‘black’.

EDITOR’S NOTE: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com – Photo credits: Dale of Norway valle-sweater