“Panem et circenses”, “bread and entertainment”. According to Giovenale, a Satirical Latin poet, this is what people want from politicians. If you give them food, personal security and make sure they can have fun, they will keep you in power, regardless of your policies. This view could be considered simplistic nowadays, but in Sri Lanka, people are increasingly taking the streets ,in an unprecedented fashion, only now that they are experiencing a shortage of basic commodities. They protested before, but you will never settle a raging mass asking for food without either resorting to violence or giving them what they want.

And what they want is the resignation of the government.

Games are over, bread is valued dearly, and the Sri Lankan government is trapped between a spiraling rise in foreign debt and a shortage of essential commodities that heightens inflation. President Gotabaya Rajapaksa has to allocate scarce resources between importing basic goods and keeping international creditors at bay. Each day he has to decide whether to feed his people or to declare a default.

But how did it come to this point?

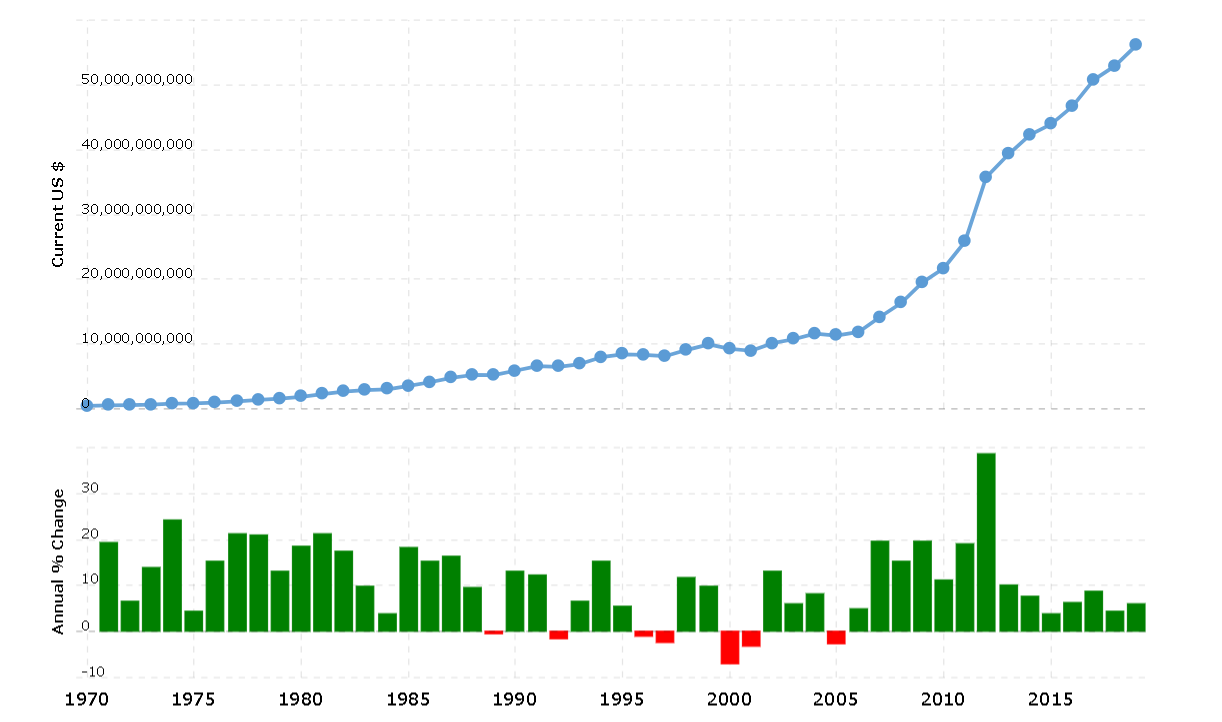

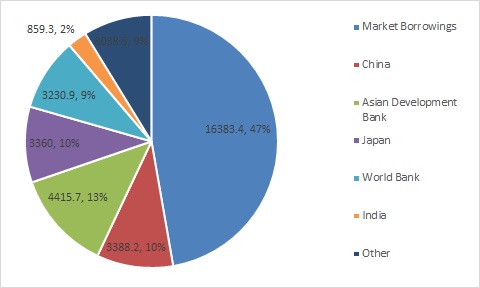

The current crisis started to be felt right before the pandemic began, but its roots can be found in the government’s political shortsightedness, starting from around 2005. As can be seen from the graphs, this is when Sri Lanka proceeded to accumulate external debt toward other countries (Mainly China, India and Japan) and international financial institutions (like the World Bank or the Asian Development Bank) apart from the general market borrowings.

Such debt was accumulated with little planning for how to repay it and without a proper strategy to sustain growth with the investments obtained through the loans.

Related articles: China’s Debt Trap Diplomacy

The Hambantota Port Deal

An example that can illustrate the Sri Lankan government’s flawed economic and political strategy is the Hambantota port deal. Considered by many commentators as an example of “debt-trap diplomacy” on the part of China, it is actually a more representative example of the Sri Lankan reckless investment strategy.

The port was inaugurated in 2010, and has since been used without total completion of the initial construction project. The total cost for phase one of the project was 361 million dollars, of which 85% was financed by the EXIM bank, managed by the Chinese government.

This deal was one of the many drafted by the Sri Lankan government in that period, and like many others, it did not yield the expected profit. The cumulative effect of all inconsiderate investment deals was that the country started to draw from foreign currency reserves to pay off the total sovereign debt. Therefore, this spiraling debt has led to a shortage of foreign currency, which the government used to pay for essential imported goods, including paper, fuel, and food.

As a result, the government is in desperate need of more Foreign Direct Investments (FDI), which could replenish foreign currency reserves and help to pay off the debt while keeping essential imports running. The problem is, of course, that economic ministers of other countries and international funds are not naïve and will not invest in a country on the brink of default without appropriate compensation.

This is why Sri Lanka was forced, in order to obtain 1.12 billion dollars in FDI from China, to lease the Hambantota port for 99 years to the holding “Chinese Merchants Port”. Therefore, the sum requested has very little to do with the (much smaller) initial amount that China financed for the construction of the port: it is instead a desperate move tailored to keeping the country afloat by stabilizing the balance of payments.

This is not to say China is not exploiting the Sri Lankan financial troubles to make a profit, but actually that the problematic situation in which Sri Lanka finds itself is due to its shortcomings rather than a Chinese evil masterplan.

What is certain is that Sri Lanka’s economy is on the brink of collapsing.

The IMF Bailout and the Current Prospects

The Hambantota deal apparently was not enough to teach financial prudence and Sri Lankan officials have been begging China and India (its two major economic partners) to open other lines of credit as a deferred loan payment – meaning a loan to be repaid in the long term, in a more suitable economic condition.

India has already provided 1 billion earlier this month and is now being requested to lend 1.5 billion more.

However, the most eloquent indicator of Sri Lanka’s financial condition is that the country requested a bailout from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Two facts show that this is truly a last resort:

- One is that Ajith Nivard Cabraal, the central bank governor of Sri Lanka, had previously ruled out seeking a bailout from the IMF, deeming it an unsatisfactory option, while now is asking for it;

- The second is inherent to the IMF loan rules: “Conditionality covers the design of IMF supported programs [through] macroeconomic and structural policies and the specific tools used to monitor progress toward goals outlined by the country in cooperation with the IMF.”

The reported passage is an extract from the International Monetary Fund regulations. Conditionality means that, if a country asks help from the IMF, it has to relinquish part of its managing authority over the money it receives.

Asking for a loan from the IMF equals admitting that you were not up to the task, that you failed in your job as an economic and political administrator, and this is precisely what the people raging the streets believe.

To say the least, they have some valid points in relation to this.

The man responsible for the policies from 2005 onwards was Mahinda Rajapaksa, who was Sri Lanka’s president from 2005 to 2015. He is now prime minister under his brother’s presidency, Gotabya Rajapaksa. The Rajapaksa family was primarily involved in corruption scandals and accusations of smothering liberal democracy.

As noted before, the financial troubles for Sri Lanka started to occur after 2005, as the country engaged in an investment spree through an increase of external debt. The country’s economy, deeply reliant on tourism for its stability and with a markedly negative trade balance, was heavily exposed to backlashes from external shocks.

The covid pandemic presented itself as that shock that catalyzed collapse in an already unsustainable economic framework.

Coming on top of the corruption and ill management of the Rajapaksa family, its (and their collaborators’) political and economic shortsightedness and the fragile structure of the Sri Lankan economy, the pandemic was a deadly blow that unveiled an underlying economic deterioration that was fermenting since 2005.

On top of all this, and within the pandemic, the government engaged in other disastrous economic policies, like the ban imposed on chemical fertilizers in order to boost organic products. This provision was badly timed, and instead of promoting organic products, it compromised crop yields leading to rising food inflation (over 10% in November, before the government removed the ban).

In this scenario, an IMF intervention looks exactly like what the country needs, as it will hopefully force Sri Lankan leaders to adopt more sustainable and sensible economic policies.

The only remaining concern is that once loaves of “Panem” drop again to an affordable price, people will leave the streets and forget their government’s profound responsibility in the unfolding of this crisis. Some Sri Lankans seem to be not so confident about their country’s prospects. Dozens of migrants are landing in Tamil Nadu, an Indian southern province, to escape what is seen by many as the most significant economic crisis in Sri Lanka to date.

One may expect opposition groups will continue to demonstrate, and maybe this crisis will lead to a political and economic restructuring of the nation which would, in turn, finally bring peace of mind and prosperity. That is something that has so far eluded Sri Lanka since its independence in 1948 when it was considered ahead of many Asian nations and could boast “exceptionally high” economic and social indicators.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: A State visit of the Sri Lankan president Gotabaya Rajapaska to India, . Featured Photo Credit: Government of India.