The disposal of hazardous wastes is one of the most important measures to avoid further disease transmission, but in the current pandemic, disposal presents particular challenges. COVID waste management will depend largely on what we learned and used from the HIV/AIDS pandemic.

Unfortunately, the two pandemics did not follow the same path of transmission. But we did learn something from the HIV/AIDS pandemic: It was a worldwide wakeup call on the need to deal with potential waste material that could infect others than those were themselves infected. HIV/AIDS was and remains a terrible threat, but its means of transmission were studied, understood, treatments developed, and made available:

“To prevent bloodborne transmission of HIV and other diseases, health care workers, emergency personnel, and others who might experience occupational exposure to blood or body fluids are advised to take universal precautions. This approach, which treats all bodily fluids as potentially infectious, includes the use of gloves, gowns, and goggles; the proper disposal of waste…”

HIV/AIDS—thankfully– was not an airborne infectious disease. We are at an early phase in understanding COVID-19, but it is aerosol, transmitted from person-to-person without any direct physical contact. As a result, it is many times more difficult to contain and touches virtually all aspects of the population, health sector, our economy, and our lives.

The current concentration of effort is correctly on finding rapid tests, therapeutics, and vaccines, getting the public to take containment measures to curb transmission and “flattening the curve”, and have it remain so. What has not received the level of attention needed is recognizing and dealing with possible COVID-19 transmission from various forms of related wastes.

With COVID waste, we are and will be dealing with two distinct categories of waste, those at “health facilities” and those “outside”.

COVID Waste at Health Facilities

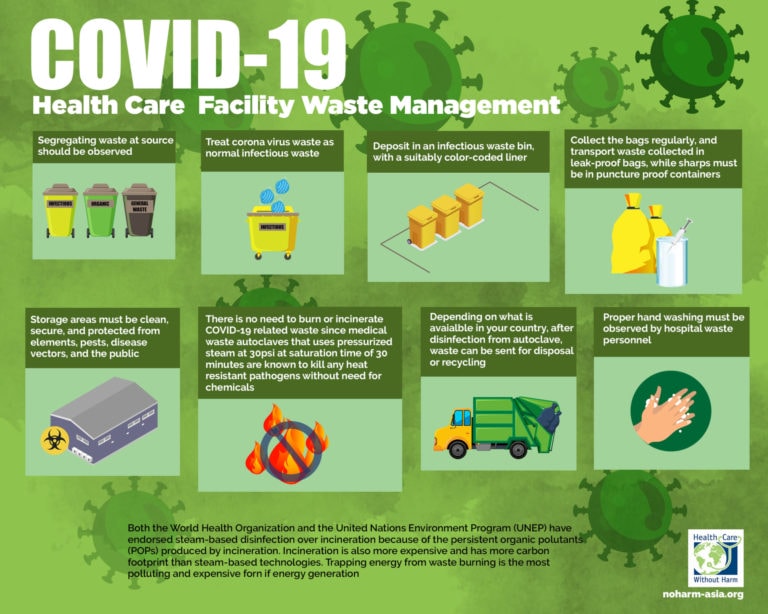

First, how to deal with health care waste. These are medical facilities, whether clinics, health posts, hospitals, which to a large degree have defined protocols, regulations, and oversight by authorities. There are also medical laboratories and biomedical research facilities that are similarly regulated.

Broadly speaking, healthcare waste can be described as anything that contains enough blood or other potentially infectious materials to spread bloodborne pathogens. These include such items as needles, syringes, scalpels. human/animal tissue, laboratory cultures, personal protective equipment, wastes from patients infected with highly communicable diseases.

Effective management of such biomedical and health-care waste requires appropriate identification, collection, separation, storage, transportation, treatment, and disposal, as well as disinfection, personnel protection, and training.

The Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal (Basel Convention) is designed to reduce the movements of such waste between nations and prevent its transfer from developed to Low- and Middle-Income Countries, and to minimize the amount of toxicity of wastes which are generated. Its Technical Guidelines on the Environmentally Sound Management of Biomedical and Healthcare Wastes provide general advice, but guidance tailored for COVID-19 is still a work in progress.

Attention to health care waste and application of guidelines varies by country. There are low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) that are more proactive than some developed countries, taking steps to both recognize the extent of the existing problem and deal with the COVID-19 health facility challenges.

The Example of Indonesia

Indonesia’s management response, through its Ministry of Environment and Forestry, and Ministry of Health, working in collaboration with WHO provides a notable example.

The Indonesian government realized early on that it had only 82 hospitals with licensed incinerators on their premise, out of nearly 2,900 hospitals in the country. So most hospitals had to rely on private healthcare waste management providers, most of whom (92%) are located on Java island. As noted by WHO, “the long distance from the hospital to the final medical waste disposal site can increase the risk of illegal dumping, cross-contamination, and disease transmission”.

Recognizing the risks, the Indonesian government planned to build five waste management facilities in the provinces and established a set of administrative measures to expedite operations of available hospital incinerators before final licensing.

COVID Waste Outside Medical Facilities

The second major source of COVID waste is “outside”. Disposal of personal hazardous COVID wastes, as a subject of public awareness campaigns in social media, has been largely “lost-in-the shuffle” despite being a subject of consequence. One need only walk in urban areas to see the number of discarded masks that lie on the ground. Not to mention the oceans:

Such COVID wastes in the “ the public domain” pose a threat, whether it be the multiple items a COVID-19 positive person wears or uses, such as masks, face shields gloves or other personal protective equipment, as well as cleaning materials now used extensively in public locations such as schools, places of worship, public events, stores, gyms, public transportation, and other service providers.

During an emergency situation such as COVID-19 the volume of such wastes increases, the likely safe handling and effective disposal decreases, which translates into secondary human health and environmental impact.

The daily amount of such material used around the world is staggering but only guessed at as there has not been in-depth analysis and assessment of the amounts or risks.

Both “health facility” and “outside” hazardous wastes, if improperly treated and poorly disposed of, pose risks of secondary disease transmission to waste pickers, waste workers, children sent or attracted to waste disposal sites, health workers, and the community in general.

The risk level depends on the nature of the waste, exposure, sensitivity, and localized adaptive capacity. While such waste may immediately harm some individuals, others will potentially affect significant numbers of people either directly or indirectly through ecosystems – for example, polluting water and making it unsafe for either drinking or washing.

Furthermore, both sources result in antimicrobial usage and antimicrobial resistance (AMR). AMR threatens the effective prevention and treatment of an increasing range of infections caused by bacteria, parasites, viruses, and fungi. Extensive use of antibiotics, antivirals, and the like, have resulted in available medicines becoming less or ineffective, infections persisting, the risk of spreading to others increases, and the emergence of “superbugs”.

AMR is a significant global problem: Antimicrobials are used extensively in animal feed to produce animal food, which is then consumed, and residual amounts enter sewerage and water sources, in a vicious circle, further building up resistance.

On 16 June 2020, the journal of Clinical Infectious Diseases published research by eight medical experts highlighting the parallel between the COVID pandemic and antimicrobial resistance, noting that this was an opportunity for mutual learning:

“The overuse and inappropriate use of antibiotics in humans and animals, and their contamination of the environment, are substantial contributors to AMR…The two emergencies are also intertwined. There is a push to resort to existing antimicrobials in critically ill COVID-19 patients, in the absence of specific treatments when supportive care alone is not enough.”

Researchers should now start collecting data to measure the impact of current COVID-19 policies and programs on AMR.

Since there has only been limited attention to quantify infectious disease wastes on a global basis for HIV/AIDS, malaria, and TB, it comes as no surprise that such COVID-19 research is in its infancy – if it is started at all.

To varying degrees countries keep data at institutional, municipal, and national levels. Inasmuch as we do not have data nor a baseline, increases from potentially hazardous waste added by COVID-19 is only speculative but probably significant.

But we know that what gets measured gets action.

What is needed for improved disposal of COVID waste

COVID-19 is likely to be with us for a very long time. If we begin to build the evidence base now, we will better know about the levels, locations, and risk, and how to respond to hazardous wastes.

As of now, there are some steps that could be taken right away:

- Raise the level of community, national and global awareness through social media

- Finalize the Basel Convention COVID-19 guidelines quickly and have countries adopt and adapt them to their situation

- Invest in waste disposal infrastructure and training by all countries

- Support research into COVID-19 waste risks including AMR, and to quantify the type, location, and health and environmental impact

Moreover, this is not likely to be enough: It will be necessary to continuously adapt, optimize, and prepare, for this and future epidemic/pandemic outbreaks. The road is long but we need to start on it as soon as possible.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. Featured Image: Screenshot from South China Morning Post video (9 March 2020) about improperly discarded masks piling up around Hong Kong beaches.