Italy has just taken a remarkable step, making vaccination mandatory for everyone over 50. We all know the pandemic has killed over five million people worldwide (5.47 million at the latest reading), and that the most vulnerable were the elderly and people with comorbidities. But what do the numbers really look like for the elderly? Is Italy’s decision to enforce vaccination on older people justified?

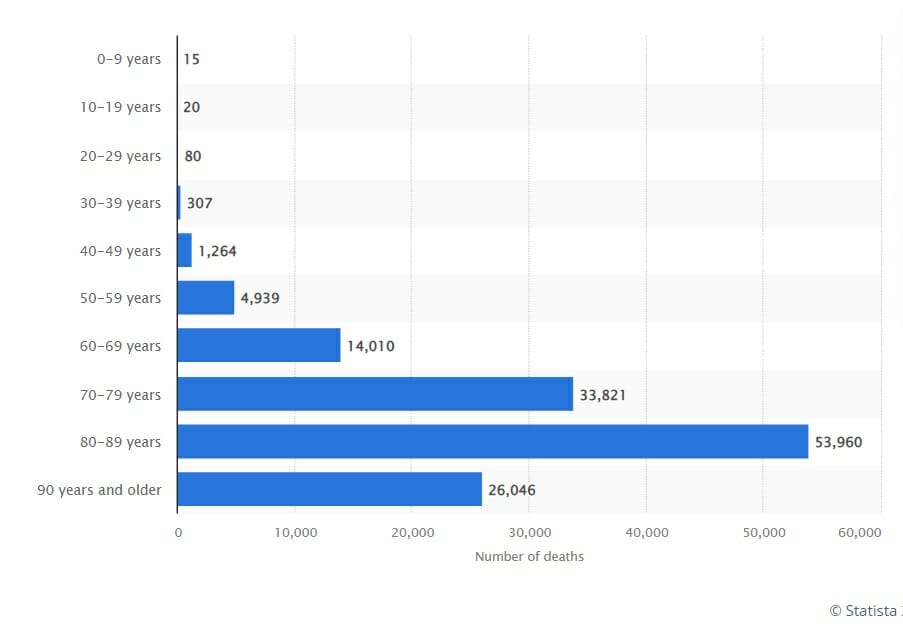

The statistics in Italy leave no doubt as to who suffered the most. This is the number of Covid deaths by age group in Italy (December 2021 data):

Of the 134.5 thousand coronavirus deaths subject of this study, almost 85 percent were patients aged 70 years and older. Italy’s death toll was one of the most tragic in the world – possibly because it is the country with the largest population of the elderly in the world after Japan.

In recent months, however, the country started to see the end of the tunnel. By December 2021, roughly 85 percent of the total Italian population was fully vaccinated.

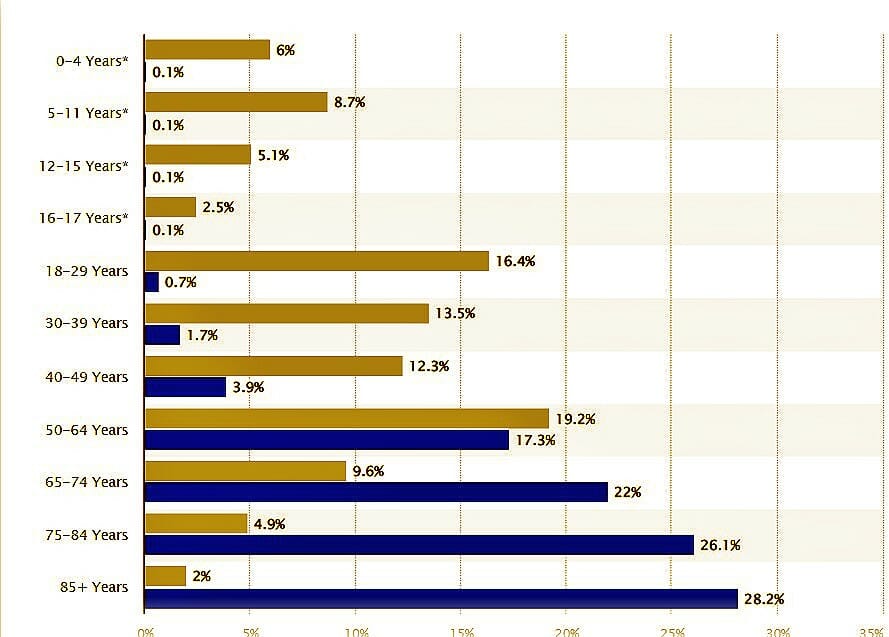

In the United States, by December 2021, at the same time as the above statistics for Italy, this is what the numbers looked like:

The above graph depicts the distribution of total COVID-19 deaths in the United States as of December 16, 2021, by age group. It shows, for example, that around 28.2 percent of total COVID-19 deaths in the United States have been among adults 85 years and older, despite this age group only accounting for 2 percent of the U.S. population.

Clearly, the risk rises with age and takes an increasing share of the population, starting with the over-50 group.

Another analysis carried out in France between March 1, 2020, and June 22, 2021, provides a striking confirmation that the level of lethality of the virus largely depends on the age of people. 73 percent of people aged 75 years and older were victims of the coronavirus:

It is too early to come up with definitive findings, but the evidence is hard to ignore. However, to give it perspective, one needs to look at another key related aspect: The heightened risk of dying from Covid for patients with comorbidities. Worldometer presents the easiest to understand comparative table of what this risk means:

It is too early to come up with definitive findings, but the evidence is hard to ignore. However, to give it perspective, one needs to look at another key related aspect: The heightened risk of dying from Covid for patients with comorbidities. Worldometer presents the easiest to understand comparative table of what this risk means:

The percentages shown above do NOT represent in any way the share of deaths by a pre-existing condition. Rather, it represents, for a patient with a given pre-existing condition, the risk of dying if infected by COVID-19. With no pre-existing conditions, the patient’s risk is 0.9%; as the table shows, people with pre-existing cardiovascular disease are at the highest risk, with the confirmed death rate at 13.2%, and the others right behind, in descending order. Put another way, a person with a cardiovascular condition is roughly 10 to 13 times more likely to die from Covid than one without any pre-existing condition. This is a brutal statistic but one must remember that when facing specific cases, this is just a probability, not a certainty.

The percentages shown above do NOT represent in any way the share of deaths by a pre-existing condition. Rather, it represents, for a patient with a given pre-existing condition, the risk of dying if infected by COVID-19. With no pre-existing conditions, the patient’s risk is 0.9%; as the table shows, people with pre-existing cardiovascular disease are at the highest risk, with the confirmed death rate at 13.2%, and the others right behind, in descending order. Put another way, a person with a cardiovascular condition is roughly 10 to 13 times more likely to die from Covid than one without any pre-existing condition. This is a brutal statistic but one must remember that when facing specific cases, this is just a probability, not a certainty.

Yet, unquestionably, people over 50 are those most likely to suffer from these pre-existing conditions. Therefore, the statistical data overlaps, but the story remains the same: Older people die the most from Covid.

Cynic observers of the human condition may be tempted to say “that’s the way it goes” and might even see a silver lining in this tragedy, claiming that public health systems are likely to find their expenditures reduced. But fortunately, most people are not so cynical and the elderly continue to play a key role in their own families.

I was encouraged to see the success among readers of a recent series of articles about the elderly published by the New York Times over seven years in 21 articles. Entitled “The Best of ‘85 and Up’: Life Lessons From the Oldest Old”, it was written by John Leland, a Metro reporter who joined the Times in 2000 and is the author of Happiness Is a Choice You Make: Lessons From a Year Among the Oldest Old, based on his experience interviewing the “oldest of the old”.

Leland had this to say when his mother asked him whether he wasn’t getting depressed, talking to all those old people: “The short answer is no. The slightly longer answer is that no work I have ever done has brought me as much joy and hope.”

His latest article, published on January 6. 2022, which recounts the passing of the last of his interviewees, Ruth Willig at 98, sounds an equally hopeful note. I was struck by his closing comment about all those people whom he’d come to know so well over the years:

“At the end of each year, I asked the elders if they were glad to have lived it. Did the year have value to them? Always the answer was the same, even from those, including Ruth, who had said during the year that they were ready to go, that they wished for an end sooner rather than later. Yes, they said, yes, it was worth living.”

Indeed, life is worth living at every age. And the family surrounding the elderly is often the first to confirm it. As one of Leland’s readers said, “Thank you for bringing dignity to these people and reminding us of the rich lives and perspectives they have. My parents died within the past few years and this article brought many memories.” I believe we all have such cherished memories, and it’s good to see – and keep in sight – the positive side of life.

The world’s major powers have resilient older leaders – Not the oldest of the old, but no spring flowers

The impact of the elderly goes beyond their family and extends to the whole of society. The easiest way to see this is to take a look at the age of world leaders. And while most politicians in Europe are relatively young, starting with France’s Macron (44), Spain’s Sanchez (49), Germany’s new Chancellor Olaf Sholz (63 ) and the head of the EU Commission Ursula von der Leyen (63) – and so is Trudeau (50) in my country, Canada -, the rest of the world reserves some surprises.

Oddly enough, the older leaders are to be found among the world’s largest powers, the US, China and Russia. Not one shows any sign of early retirement. Yet, they are not young: Xi Jiping, the youngest at 68, has obtained what he wanted, to remain indefinitely at the helm of China. Putin, age 69, likewise, is not about to leave the Kremlin. Biden, currently 79, will be 81 in 2024 at the presidential elections when he is likely to face Trump who will then be 78.

None of them could be described as the “oldest of the old”, but they are definitely not spring flowers. The rest of the world tends to have younger leaders although some older ones stand out: Modi in India (71), Erdogan in Turkey (67), Duterte (76) in the Philippines – but he appears to be on his way out. The Prime Minister of Italy, Draghi is 74 – and as I write, there is an ongoing debate in Italy as President Mattarella (80) is stepping down and a new President must be chosen by Parliament.

Among the candidates, incredibly, is Silvio Berlusconi at the grand old age of 85. If elected, he’d be 92 by the time he finishes his term. But then why not? Giorgio Napolitano who was President of Italy from 2006 to 2015 is still alive at 96.

Golda Meier once said “Old age is like a plane flying through a storm. Once you’re aboard, there’s nothing you can do.” A fine saying as long as you’re not an old political leader who’s taken on board that plane along with himself all the people who have voted him. Who wants to fly through a storm?

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists and contributors are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: Frankfurt Rossmarkt, Coronaprotest by an anti-vaxxer claiming vaccines will change human DNA, thus showing a complete misunderstanding of how mRNA vaccines work, photo taken July 18, 2020 Flickr (CC)