Beyond the primary tasks of providing swift and effective health care delivery during the COVID crisis, nation-states must next turn their attention and policy expertise to an analysis of the ways in which their economic policies and prescriptions have failed to meet the demand of this unprecedented global health challenge. Neither capitalist nor socialist constructs have demonstrated sufficient capacity to deal with the various demands of the current circumstances. This suggests the need for some hybrid or reconstructed form — a new paradigm for society if you will. What is termed “Inclusive Capitalism” may offer some answers, although some have critiqued it, arguing that it does not address a critical factor, the sharing of political power.

The ongoing COVID crisis has accelerated demands for review and rethinking of economic systems, at both ends of the spectrum, but especially those which have held themselves out as “capitalist” in contrast to those with “socialist” intellectual foundations.

It is fair to say that in this twenty-first century there are very few if any, “pure” economies of one sort or the other. But for those who espouse deep, bedrock capitalist sentiments, there is no getting away from the reality that there has been a shift to a more interventionist government.

A short-list of support policies to troubled sectors of an economy shows an extensive range in response, from financing research and delivering therapies and vaccines to assisting small businesses affected by the pandemic, including the provision of tax breaks or directly helping those thrown out of work through no fault of their own.

Whatever and wherever, it is important to underscore that in many countries, private sector individuals and entities have been the principal inventors, manufacturers, and distributors of COVID materials. It is also similarly the case with the role of government: the response to COVID has involved and relied upon state-sponsored or funded research laboratories and laboratory scientists, public sector networks for surveillance, distribution, and infrastructure, and beyond that, relying on subsidized financing, policies, and state regulatory authority to fulfill its role.

Societies differ, however, in how and to what extent they rely on and choose between these two approaches.

Core contrasts between a country like the United States which views capitalism as the reasons for, and the pinnacle of its success, and the alternative perspective of much of Europe, is worth considering.

From Capitalism to “Inclusive Capitalism”

The seeds of capitalism arguably can be said to have found fertile ground and taken root in the energy of the New World colonies, and from the work of Thomas Hobbes.

In 1651, in his landmark book “Leviathan”, Hobbes posited that people were “motivated by appetites, desires, fear and self-interest”. When the colonies became a country, the United States 125 years later, Adam Smith’s “An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations” published in 1776, took Hobbes’ fundamental idea a key step further and made it into an economic justification. He argued that giving everyone freedom to produce and exchange goods as they pleased (free trade) and opening up markets to domestic and foreign competition, would convert people’s natural self-interest into a higher goal resulting in greater prosperity, rather than relying on stringent government regulations to provide for the individual and public good.

At the heart of Adam Smith’s views is that the government should not repress people’s self-interest which is what drives people more than kindness or altruism (though he never underestimated the force of moral emotions and wrote extensively about it). These lines of thinking were reinforced by the dominant religious values of Protestantism which rejected “pre-determinism” and emphasized that each person, taking into account their set of beliefs, should be able to chart their own life path and make sound judgments for the good of all.

Looking at these building block concepts, throughout its history the U.S. has considered itself the principal defender of capitalism, the reason for its “exceptional”, strength, growth, and source of invention and innovation. Faced with enormous 20th-century challenges including an economic collapse and two World Wars, the American version of capitalism changed to some degree, while the core idea was never abandoned. Canadian born economist, John Kenneth Galbraith, reflected this evolution in his 1951 book “The Concept of Countervailing Power”:

“The producer now has measurable control over his prices. Hence, prices are no longer an impersonal force selecting the efficient man, forcing him to adapt the most efficient mode and scale of operations and driving out the inefficient and incompetent. One can as well suppose that prices will be an umbrella which efficient and incompetent producers will tacitly agree to hold at a safe level over their heads and under which all will live comfortably, profitably and inefficiently.”

Europe experienced an equally turbulent 20th century but drew on a different history, and from other philosophies that took strong root in shaping many of its leading societies.

In the post-World War I and II periods, socialism probably had its largest and most sustained impact. Karl Marx, who developed the idea that societies evolve through class conflict, critiqued capitalism by analyzing the division of labor in Europe from a historical perspective. He argued that people’s human nature, more specifically their ideas “were largely a product of class, economic structures and social positions. These ideas justified or rationalized the economic structure at any one time – they did not cause that structure”.

Marx concluded that the division of labor contributes to inequality between low-income workers and the upper classes. Workers are far more numerous and their wealth is far less than the upper classes who are a minority and hold far more power as they usually include businessmen and politicians. Marx’s historical perspective focused on the role of politics in contributing and legitimizing modes of production that created separate socioeconomic classes. Along with much of Europe, Canada, unlike the United States, pursued a more socialist orientation than its neighbor.

With economic collapse, shifts in the world order, and a global pandemic, the twenty-first century has had and continues to face seismic challenges. This has generated searches for new ways to take advantage of the main systemic constructs.

One such effort is encapsulated in “Inclusive Capitalism”, which emerged after the financial crisis of 2007-2008 and subsequently advocated by a 2015 non-profit organization, the “Coalition for Inclusive Capitalism”. The Coalition, founded by Lady Lynn Forester de Rothschild who is also the CEO, is currently actively seeking to draw the attention of the Biden Administration on the need to reform the way society “treats those in power” and thus formulate a “new compact” with American workers; it is doing this together with the Rockefeller and Ford foundations calling for a bipartisan approach:

Mark your calendars for Wednesday’s live-streamed #RFBreakthrough episode to kick off the new government term with the launch of @InclusiveCap’s Framework for #InclusiveCapitalism, 21 bipartisan policies for a new compact with American workers. Join us: https://t.co/WkiPI5uWOq pic.twitter.com/xNnhYzuGub

— CECP (@CECPtweets) January 28, 2021

On 27 January 2021, the need to reform capitalism was forcefully highlighted at the World Economic Forum (Davos) by the Ford Foundation President:

Capitalism must be reformed if it is to be sustained, says @FordFoundation President @darrenwalker.

You can watch the session here: https://t.co/QCOK1sIItv#DavosAgenda pic.twitter.com/ALrmHcqyIa

— World Economic Forum (@wef) January 27, 2021

Broadly speaking, “Inclusive Capitalism” has two main conceptual pillars: (1) lift people out of poverty and (2) power global innovation and economic growth.

Poverty is a systemic problem in countries that have already embraced or are transitioning towards capitalistic economies; and the objective in “inclusive capitalism” is to encourage businesses and non-governmental organizations to sell goods and services to low-income people, which will assist in targeting poverty alleviation strategies including improving people’s education, health care, nutrition, employment, and environment.

The concept recently raised the attention of diverse interests. In 2019, the Embankment Project for Inclusive Capitalism (EPIC) undertaken by the Coalition together with Ernst & Young sought to “develop a framework and identify meaningful metrics to report on long-term and inclusive value creation activities that heretofore have not been captured on traditional financial statements”.

In 2020, from a vastly different perspective, the Vatican has joined in a partnership for this purpose. To address the fast-growing global wealth inequality between the ultra-wealthy and the rest of society, Pope Francis proposed a “challenge to corporate executives and public sector leaders to adopt a more inclusive, fair and transparent economic system” that focuses on both humanity and the environment.

In response, the Council for Inclusive Capitalism will serve as a movement calling on businesses to join in addressing the challenge and declaring their commitment to change from a purely profit-driven model to a “dual one”, more “inclusive” that would also include the poor, the emarginated and our planet Earth:

Signs are that leading American capitalists are hearing the call for a dual model.

A 2019 statement of purpose by the Business Roundtable calls for a change from the principle of maximizing shareholder value, to the concept of maximizing “stakeholders’ value”, ie. business goals should include “commitments to all stakeholders” – not just shareholders.

That said, there are serious criticisms of the concept, underscoring its limitations, namely the apparent separation of economic aspects from political power leading to a failure to address core poverty alleviation issues. An article in The Guardian by Nafeez Ahmed in 2014, called it a “Trojan horse to quell the coming global revolt” and put it this way:

“… Inclusive Capitalism Initiative has nothing to say about reversing the neoliberal pseudo-development policies which, during capitalism’s so-called ‘Golden Age’, widened inequality and retarded growth for “the vast majority of low income and middle-income countries” according to a UN report – including “reduced progress for almost all the social indicators that are available to measure health and educational outcomes” from 1980 to 2005.”

Furthermore, there are also many economists who see the situation differently. One group, termed the “institutional economists” argues there is no such thing as “free” competition or “free” markets, that markets are in fact always regulated. Economic life, de facto, takes place in the shade of a society’s institutions, customs, and traditions – all “institutional” factors that need to be taken into consideration to devise effective policies.

Among these institutional economists, the work of two women stands out. One is Italo-American Mariana Mazzucato, author of the Entrepreneurial State (2013) who highlights the foundational role of government in basic research and in stimulating innovation, that technological progress is not just the result of the “free market”. The other is British Kate Raworth who forcefully argues that endless economic growth as advocated by neo-liberal economists makes no sense in a world of finite resources and that an entirely new economic model is needed.

Notwithstanding, the twin Inclusive Capitalism pillars are indeed embedded in the aspirational United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), sought to be achieved by 2030 and central in dealing with COVID-19. Without government and global policies that encourage individual and private sector initiative, and provide the wherewithal to protect society’s weakest members, prospects that we will conquer this virus – or the next – are slim.

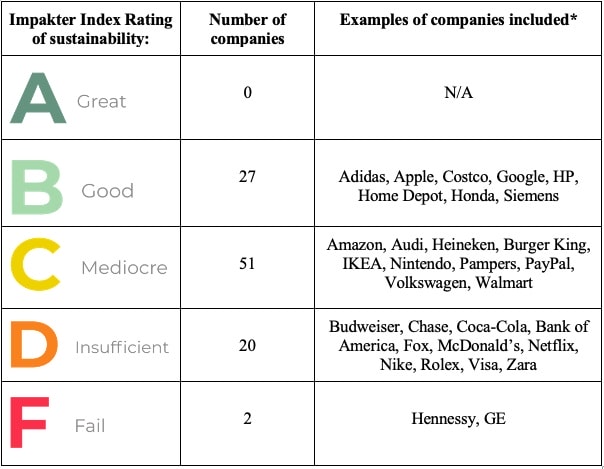

One recent example of evolving ways for the consumer society, the private sector, and the SDGs to do common cause, is in the establishment of an objective, an arms-length independent rating system of business performance in addressing environmental impacts, of value for their own purposes and to inform eco-conscious consumers. The Impakter Sustainability Index has just come onstream and serves that very purpose. The world’s top 100 brands have been rated on the Index, and the findings are that, despite claims to the contrary, the goal of sustainability remains elusive – and possibly unattainable for those businesses that continue to partner with the oil and gas industry.

A summary of the Top 100 Global Brands:

Returning to our present public health COVID emergency. Clearly, there are emerging ways businesses and governments have and can use to collaborate to help low-income populations obtain access to COVID-19 therapy and vaccines. Applying inclusive capitalism to allow selling goods and services to poor people and poor nations at affordable prices, and maintaining a reasonable profit, while addressing structural inequalities are elements in the way forward.

Such public-private partnership collaboration is happening with the World Health Organization’s multi-billion-dollar effort, the “Access to Coronavirus Tools-ACT Accelerator”. The ACT-Accelerator objective is to provide subsidized access to COVID-19 vaccines to poor countries; the U.S., the last major holdout, has just joined as one of the first Executive Orders of the new U.S. President and expressed an intention to make a multi-billion-dollar commitment. There are many other similar instances and examples in the health sector and elsewhere.

COVID-19 is a human and economic disaster of unimagined proportions. However, it provides an opportunity to recognize and build on the strengths and weaknesses of economic-social “isms” and meld the different parts for the benefit of everyone.

At an Aspen Ideas Conference in 2020, before the pandemic exploded worldwide with millions infected and dead, Jeffrey Sachs, an American economist who is the Director of the Center for Sustainable Development at Columbia University, said that with our current advances in technology, “we can choose to do the ultimate good or create unimaginable disaster.”

Let us hope leaders find the right blend of concepts, policies, and incentives to get us to a better place.

EDITOR’S NOTE: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com.— In the Featured Photo: Adam Smith’s “invisible hand”, held up by economists Milton Friedman and Friedrich Hayek, the founders of the neoliberal ideology, is described here as an “invisible boot” to workers – drawn from BBC video (screenshot)