Policies aiming to contain migration by force are a mistake. Here’s why.

Emigration is a consequence of political and economic corruption in Latin America. There are structural conditions that expel and oblige citizens, more specifically from Guatemala and other countries in Central America’s Northern Triangle, to flee from their countries despite the high risks involved in such endeavors. Many of these structural conditions are based on economic factors, which are in turn tied with social and political variables. Some factors include poverty, violence, malnutrition, socioeconomic inequality, racism, social discrimination, and political exclusion.

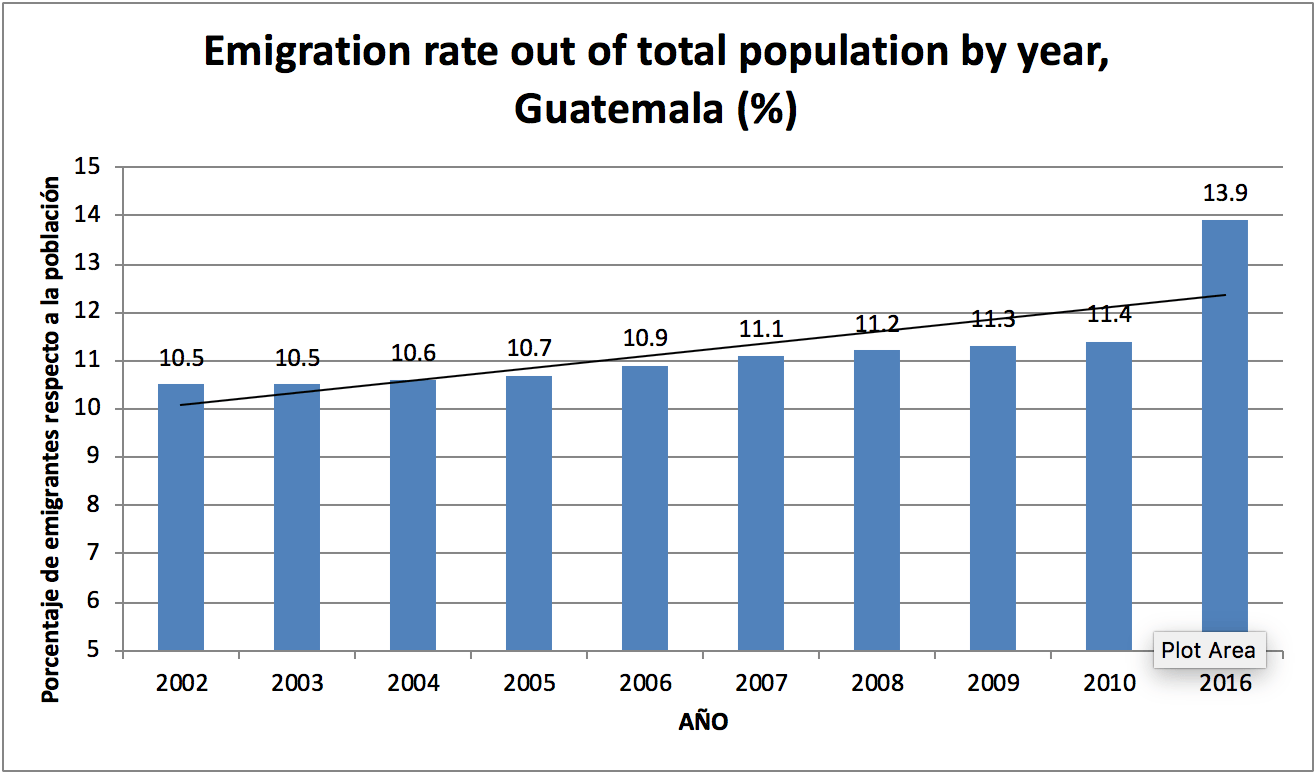

Most migrants are peasants from indigenous backgrounds or young people from households below the poverty line. According to IOM, more than 300 people leave the country daily and 2.5% of them are minors. Just 63% of all emigrants arrive at their final destination. By now, there are more than 2.5 million Guatemalans living abroad.

Income Inequality and Poverty and their Impacts on Migration

When I refer to inequalities as one of the structural problems in Guatemala, I do not refer only to income inequality but also to lack of access to income determinants. For example, there is a lack of access to health services, education, and entrepreneurship tools as well as limited access to financial capital and land. Furthermore, it is extremely difficult to overcome socioeconomic barriers that one is born in to.

The income Gini coefficient in Guatemala has been 0.53 on average in the last 20 years, putting the country almost exactly in the middle of complete income equality (0) and complete inequality (1). However, 8% of landlords own 92% of productive land (World Bank 2012), meaning that the other 92% of landlords share the remaining productive land. Considering this statistic, the Gini coefficient may not be an all-encompassing representation of the Guatemalan economy.

There is plenty of evidence that a determinant factor of poverty is a lack of access to means of production and opportunities. The groups with the least opportunities are indigenous women from rural areas and poor households from urban areas. 59% of the Guatemalan population lives below the poverty line. 5 out of 10 children below 5 years old are chronically malnourished, and that number jumps up to 8 out of 10 when considering solely indigenous children.

Inequality is a large aspect of poverty. And, in countries like Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador in which assets and economic opportunities have been given to a concentrated, elite group, and in which income sources are historically distributed asymmetrically, poverty reduction requires more than just faster economic growth rates. The spillover effect does not take place in such structures. The State has been insufficient in addressing the structural problems that are responsible for this growing inequality.

Guatemala’s Economic and Institutional Structures

Both taxes and government expenditure in Guatemala are regressive. Corruption prevails and, as a consequence, institutions remain weak.

USAID and common policies adopted from North America have supported economic growth and market liberalization. They have been successful in terms of keeping a stable, although small, economic growth rate. However, there is evidence to prove that without addressing the structural unequal access to income determinants and financial opportunity, economic growth is insufficient for Guatemala as a whole.

Pro-growth economic policies have been in place in Guatemala since the late 80’s. Privatization, market driven action and market-intensive policies have reduced government intervention to its minimum. In fact, according to the libertarian think tank Fraser Institute, Guatemala is considered the country with the world smallest government.

However, the issue of socioeconomic disparity has not been addressed structurally with a long-term development strategy. The Guatemalan government’s economic policies in the last 20 years have been mainly supply-side based. Their purposes oscillate between incentivizing entrepreneurship, improving physical infrastructure, creating macro-economic stability, and reducing poverty. Clearly, these policies have not been successful in deterring people from migrating.

Although the foreign direct investment (FDI) has been relatively low, it has not been particularly focused on labor intensive industries. Government investment in infrastructure has been around 1% of GDP and private investment has been around 10% in the past 10 years. Guatemala hasn’t had a recession in the last 15 years, even during the financial crisis, despite the U.S. being its greatest trading partner.

Editor’s Picks — Related Articles:

Capitalism is Broken, Here’s How to Fix It

Something is Brewing in Guatemala: It’s Bold, It’s Strong

What Guatemala Taught Me That Switzerland Could Not

Government Corruption and its Impact on the Economy and Migration

However, the mentioned policies have not sufficiently addressed the deep socioeconomic problems in Guatemala, including the entrenched racism and systematic exclusion of certain populations (particularly indigenous women from in rural areas).

The government’s income and expenditures have been among the world’s smallest. In fact, the government’s budget has been in a structural deficit due to the lack of public resources allocated towards reaching urgent social demands including access to food and basic health services. Chronic malnutrition has increased under the current administration among other human development factors, and the government is doing little to combat this issue.

Oligopolies are the norm and a lack of access to credit, property, and basic services prevails, particularly within indigenous groups and first nations. Corruption is rampant and there is evidence which confirms state capture by criminal groups, politicians and economic elites (CICIG,2017).

Government officials have used their authority and power for private gain in designing and implementing public policies. Last week, a former mayor of the Chinautla Municipality was released from charges of abuse of authority, embezzlement for theft, and illicit association even though there was enough evidence of his corrupt actions to indict him.

Private individuals tied with criminal groups as well as corporate cartels and military factions have also been accused of obtaining large shares of public funds while simultaneously bearing a lower share of public costs. Social public spending is a mere 3.9% of GDP which is the lowest in Latin America, and government revenues have been decreasing over the last 5 years.

Corruption also distorts the government’s role in resource allocation. There is empirical evidence that corruption is likely to economically benefit well-connected citizens who are mostly in the upper class. Thus, corruption would affect not only macroeconomic variables, such as investment and growth, but also income distribution, further increasing the gap between the wealthy and impoverished. Moreover, strategies aimed to promote growth via capital-intensive projects while lowering investment in labor intensive industries are likely to increase poverty and decrease financial opportunities for lower income groups. De facto powers controlling institutions and impunity is once again becoming the status quo.

The Disruptive Power of the CICIG

Guatemala had a small window of disruptive policies that sparked some hope amongst mostly urban population and some elites. This movement started in 2015 with two high impact cases in which the former President, Otto Perez Molina and Vice President, Roxanna Baldetti, were accused of corruption.

With some challenges, the International Commission Against Impunity (CICIG) did what had never been done in Guatemala before. They demonstrated that impunity can be fought and that traditionally powerful groups, including the economic and social elite, can be put on trial and held responsible for their actions.

However, the CICIG soon lost power. The commission (including former Commissioner Velasquez and former Attorney General Thelma Aldana) became the target of obscure groups and was successfully portrayed as the enemy by the entrenched mafia. This instance conveys the large amount of power that the mafia holds and their influence on institutional structures in Guatemala. Even current President Morales, who is being accused of participating in illicit finance, declared Commissioner Velasquez “Non Grato” or “Not Welcome” in 2017.

Termination of CICIG only aids the criminal structures responsible for human trafficking as well as drugs and other illicit activities. In turn, violence and migration trends both increase in volume.

The Guatemalan economic structure depends on remittances, which have been increasing each year and which support more than 1.5 million households. If these households did not receive remittances, they would be more vulnerable to violence, illicit acts and drug trafficking. They would also be subject to more demands from the government and other social issues.

Remittances are a strong component of the Northern Triangle’s GDP. This form of income represents 22.2% of GDP in El Salvador, 20.3% in Honduras, 11.8% in Guatemala and 10.3% in Nicaragua (ECLAC, 2019).

Human rights commissioners continue to report rights violations of indigenous groups, and human development reports convey the precarious situation of most Guatemalans.

These structural problems are the ones that continue to pressure Guatemalans in to fleeing the country and finding ways to escape from these realities which present no hope for a better future. We are not talking about the guerrillas from the 80’s. We are talking about economic repression from multinational extractive industries which take land from communities and use it for palm oil plantations, and extraction of coal and oil.

Emigrants from Central America’s Northern Triangle to the USA don’t want to achieve the American dream. Rather, they are escaping from the Central American nightmare.

Emigration rates have continued to rise, even after policies were implemented for faster economic growth. Even though a few income growth initiatives were achieved in certain urban demographics, wealth concentration keeps rising while poverty has increased in Guatemala.

Where do we go from here?

The policies that should be addressed are not the ones that aim to contain migration by force. Guatemala by no means has the capacity and institutional structure to become a “Safe Third Country”, as Trump’s administration wants it to be. With rampant corruption, vulnerable institutions, increasing poverty, high inequality, unsolved social problems, drug trafficking, and a state captured by mafias and impunity, Guatemala can guarantee neither safety nor stability for any person living inside its boundaries. The emigrating contention policies will be a failure and thus, a mistake.

Let’s try to move away from our western views and take off our northern hemisphere glasses. The issue in the Northern Triangle is not about people migrating, but rather a failed state that has remained in the hands of mafias and powerful elites. It is about a democracy that has been hijacked by a historic structure of exclusion and privileges. A time bomb is about to explode in the backyard of the United States if the only escape vault for thousands of people is sealed.