Providing residents in key conservation areas with a conservation basic income (CBI) — an unconditional cash transfer — is a “potentially powerful mechanism” for facilitating the necessary shift in conservation, suggests a new study that estimates the potential costs of implementing the CBI scheme on a global level.

Published last month in Nature Sustainability, the study explains how the CBI can help foster sustainable development, mitigate climate change, protect biodiversity and preserve ecosystems. It estimates the potential costs of the scheme at billions or even trillions of dollars per year, but argues that the long-term benefits outweigh the costs, with the authors describing it as a “wise investment.”

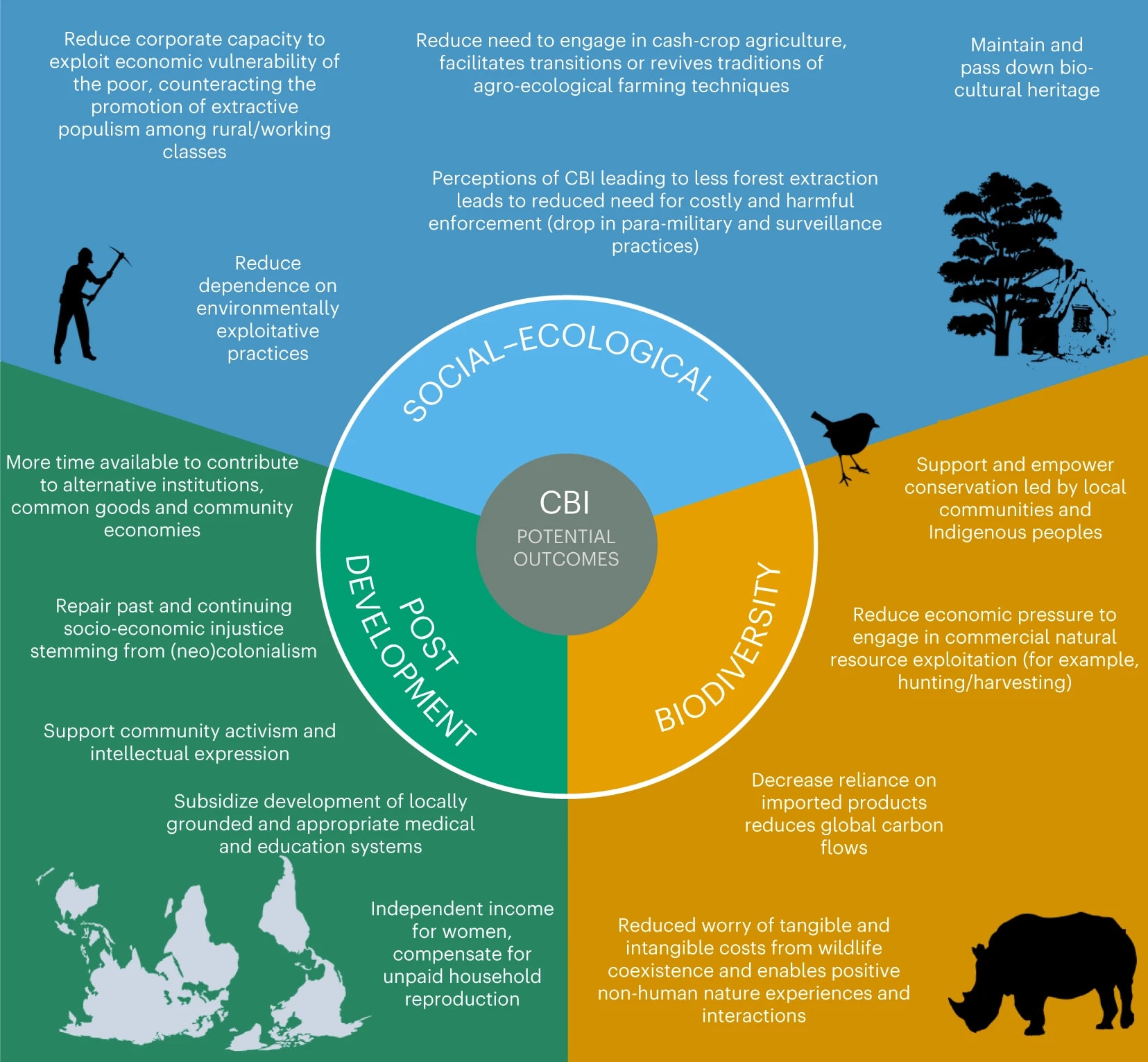

How CBI can facilitate the shift in conservation

“Achieving internationally agreed targets to halt biodiversity loss, restore degraded land and mitigate climate change requires transformative change in global economies,” the authors write.

They explain that there are several “key leverage points” to focus on if we want to achieve these targets, including “reducing aggregate consumption, unleashing existing pro-environmental values, embracing diverse visions of a good life, reducing inequalities and practising just and inclusive conservation.”

The researchers say that CBI can play an important role in biodiversity conservation and “support a just transition to sustainability through these leverage points.”

According to the paper, “effective, sustainable and equitable biodiversity conservation requires empowering and supporting Indigenous peoples’ and local communities’ (IPLCs’) connection to and stewardship of nature.” CBIs, says the study, can help to reduce IPLC’s dependence on environmentally exploitative sources of income such as cash crop farming, poaching, and waged labour in extractive industries.

The researchers also say that CBIs can increase the political power of IPLCs, enabling them to “negotiate and demand environmental protections” for their lands. This is also useful for protecting biodiversity as it ensures IPLC stewardship of the land to protect “bio-cultural heritage, commons and resilient socio-agroecological systems.”

So how much would it cost?

Similar to universal basic income (UBI), the proposed CBI scheme would be in the form of “unconditional cash transfer.”

The study explains that the gross costs of CBI would differ depending on the areas and populations it applies to. If each individual receives the equivalent of US$5.50 per day, the researchers expect the total annual global cost of CBIs to be between US$351 billion and US$6.73 trillion.

The report used spatially explicit human population data to estimate the number of people eligible for a CBI — “residents in areas receiving conservation attention” — at between 232 million and 1,638 million, 75-88% of whom live in low- or middle-income countries (LMICs).

According to National Geographic, the most biodiverse regions are found closer to the equator. This is because they are warm all year round and are typically tropical. There is also an overlap between countries with high rates of poverty and countries with high biodiversity.

There are different models for funding LMICs. Through a flat payment rate, LMICs would receive over 75% of the funds. The second largest share would come from a rate proportionate to that specific country’s GDP, around 40-61%, says the report. Tiered scenarios would produce the smallest share of 38-45%.

At a flat rate of US$5.50, the report says that “the gross costs allocated to each region are proportional to the eligible populations.” But when the payments are proportional to a country’s GDP or tiered, wealthier regions such as East Asia and Europe receive more money.

Related articles: How Local Governments Can Lead the Biodiversity Movement, Over Two-Thirds of Wildlife Lost in Less Than a Lifetime, The Mass Extinction Crisis: Can the Private Sector Help Solve It?, What Is Rewilding and Why Is It so Controversial?

The report argues that if 44% of terrestrial land (the minimum required to adequately protect global biodiversity) were subjected to conservation efforts, an estimated 1,638 million people would be affected, with the vast majority, 1,448 million people, living in LMICs.

Estimated gross cost for this scenario “at one quarter (+5%) of national GDP is US$5,609 (± 1,112) billion annually and US$3,438 (± 685) billion (61%) in LMICs,” the report finds.

The flat payments of US$5.5 would cost US$3,289 billion globally or US$2,906 billion in LMICs, according to the report.

Examples of similar initiatives: Costa Rica and Indonesia

The report cites Indonesia as a country that was able to reduce deforestation through an anti-poverty cash transfer scheme. Home to one of the largest cash transfer programs in the developing world, Indonesian authorities provided temporary assistance in the form of US$10 per month, according to Poverty Action Lab.

This helped 19.2 million households survive rising fuel costs between 2005-2006 and 2008-2009.

Costa Rica is another example of how payment initiatives can preserve biodiversity. By 1995, forest cover in Costa Rica had reduced to just 25% of the national territory compared to over half in 1950. In 1996, the government outlawed deforestation and introduced the Payments for Environmental Services (PES) Program in 1997.

It is possible: How Costa Rica doubled the size of rtainforests in a generation:

*Restricting logging

*Paying landowners that conserve their land

*Investment in eco-tourism

Now forest cover almost half the country@RainforestNORW @wef pic.twitter.com/pM6mPUBz2X— Svein Tveitdal (@tveitdal) July 3, 2021

Through the PES Program, landowners in Costa Rica “receive direct payments for the environmental services that their lands produce when adopting sustainable land-use and forest-management techniques,” according to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

A total of over 1.3 million hectares fall under PES contracts in Costa Rica, and “more than 18,000 families have benefited from the program.” The program aims to promote “carbon sequestration, biodiversity protection, water regulation and landscape beauty.”

Since 1995, when only 25% of Costa Rica was covered by forest, the country has grown to “become one of the world’s leading proponents of environmentally sustainable development.”

From this example, we can see how effective it can be when landowners are paid for their environmental efforts. Whilst this is an excellent way to preserve biodiversity, it is costly and does depend on whether a country’s government is able to afford CBI or a similar payment scheme in the first place.

However, as the study’s authors note, “these costs are large compared with current government conservation spending (~US$133 billion in 2020) but represent a potentially sensible investment in safeguarding incalculable social and natural values and the estimated US$44 trillion in global economic production dependent on nature.”

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: A rainbow macaw in Costa Rica Featured Photo Credit: Unpsplash