On Friday July 26th, people in more than 80 Colombian cities and in 58 other cities worldwide participated in the “March for Life,” demanding justice for the nearly 500 Colombian human rights activists and peace campaigners who have died since the signing of a peace accord in 2016 between the Colombian government and the FARC (the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia). The protesters also appealed to the Colombian government and asked for better protection for social leaders who work with the communities that are directly affected by the agreement.

President Iván Duque‘s policies and inaction have put Colombia’s peace process at risk of failure. They have done little to protect peace and human rights activists. Thus, it isn’t surprising that when Duque participated in the March for Life in Cartagena, he left prematurely under chants of “Get out!” and “Murderer.”

Yes, these are Colombian issues. But they also happen to be of regional and global importance and are deserving of multilateral and multifront responses. Drug trafficking is a global problem. Alternatively, human trafficking is a regional concern, especially given the Venezuelan refugee crisis. Without the international community’s concerted efforts and continued material support of peace advocates in the national congress and civil society, the promise of peace will wither and die from the intentional neglect and general hostility of the Duque administration.

Colombia has a long, sad history of political violence, including the longest running leftist insurgency in global history (from 1964 to 2017). The FARC emerged in 1964 as the armed wing of the Colombian Communist Party. The guerrilla group initially limited itself to small scale assaults in rural zones before attacking in cities and on military garrisons, which began in the 1980s. The cocaine boom (la bonanza coquera) funded the latter brazen attacks. Attempts to come to a negotiated solution with the state had been on and off.

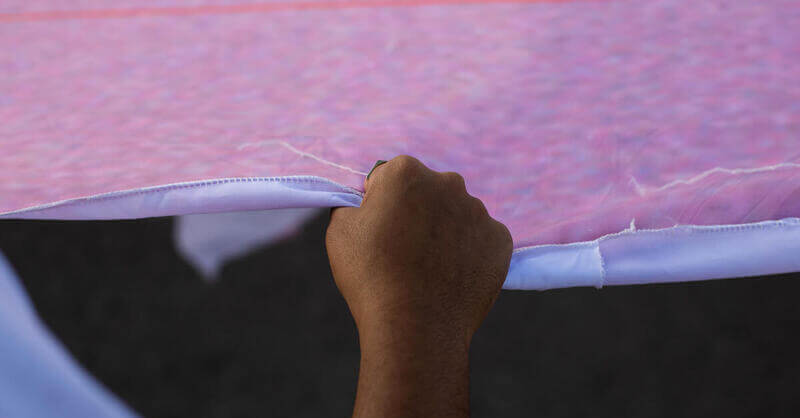

Photo Credit: Steven Grattan @sjgrattan

A sustained Colombian military campaign that began last decade and which assassinated key FARC leaders, combined with the natural death of its longtime leader Manuel Marulanda in 2008, compelled the insurgent group to pursue an agreement with the state in earnest.

Sponsored by the Cuban and Norwegian governments, peace talks began in 2012. The talks, mostly carried out in Havana, led to a cease fire in June 2016 and the signing of the accord in August 2016. These tense discussions produced a deal with the FARC that was and will remain deeply controversial. In preparation of presenting the Colombian public with a final accord, the government of the then President Juan Manuel Santos began a public relations campaign to sell an agreement that had not yet been made public. The initial accord lost a national referendum by less than half of a percentage point, forcing Santos to revise it modestly and use Colombia’s Congress to ratify it in November 2016.

The most contentious elements of the original accord remained in the revised version, including allowing the FARC to form a political party and stand in elections. Furthermore, the issue of restitution to the families of the approximately 220,000 people killed during this half-century conflict upset many, as it seemed there was little in the treaty to satisfy the bereaved. While imperfect, this accord presented a platform on which Colombia could pursue reconciliation. It satisfied 13,000 FARC fighters enough to hand in their weapons and end armed struggle. The ultimate success of the resolution, however, remains firmly in its implementation.

Political will, insecurity, impunity, and the economy are all variables that endanger the goals of demobilizing FARC militants and decommissioning their weapons. Peace campaigners in the Colombian congress and in civil society are diligently pressuring the Duque administration to make good on the peace settlement and to build public support. Yet, they have made it clear that international support must be strong and decisive as peace activists and demobilized fighters continue to be assassinated.

Editor’s Picks — Related Articles:

Colombia: A Divided Country in Search of Peace

Youth, a Not-So-Secret Formula for Peace and Sustainable Development

Containing Migration is a Mistake

The principal reason for the current dismal state of affairs in Colombia is a lack of political will on the part of President Duque, who campaigned against the settlement negotiated by his predecessor and Nobel Peace laureate, Juan Manuel Santos. Duque won the presidency in a runoff against Gustavo Petro, a former mayor of Bogotá, ex-militant, and flawed candidate with limited appeal. Assuming office in August 2018, Duque’s election cannot be interpreted as a vote against the peace process because he was seen as an alternative to a lesser candidate.

Duque has been slow to enforce implementation of the accord since, despite being bound legally and constitutionally to implement it. He even sought to strike a blow to the transitional justice framework that was so difficult to craft. In March, the president effectively vetoed six articles of a bill that would oversee the special courts in which combatants on all sides agreed to be tried.

Instead, Duque’s concerns center on reparations, identifying those offenders who were maximally responsible, and on the issue of extraditing former fighters to the United States. Colombia’s lower house rejected this move as did the Senate. Yet, Duque’s supporters argued that the Senate’s vote was null and void because a quorum was not achieved. Colombia’s highest court rejected these objections and Duque signed the legislation into law in June.

A group of legislators expressed the urgency of this situation to the UN Security Council delegation in Bogotá earlier in July, asserting that “dark forces” surrounding the president were intent on securing the failure of the peace process. These episodes are indicative of Duque’s opposition to the peace process as he continues to inhibit the swift implementation of the treaty. And, the consequences are dire and manifest.

With the glacial pace of implementing the accord, the Colombian government has lost valuable time in developing its presence in areas once dominated by the FARC. Instead, FARC dissidents, drug trafficking organizations, and the last remaining leftist guerrilla movement, ELN (National Liberation Army), have filled the void.

Shakedowns and kidnapping incidents continue to increase. The resulting insecurity has left hundreds of social leaders dead, more than 200 former fighters assassinated, and thousands of civilians displaced. Rural development was a key component of the peace treaty and a key element in persuading the FARC to end its campaign. Yet, the promised roads, schools, and development aid have yet to be implemented. If the Colombian state is present in these areas, it is in the form of military, which has not cultivated trust among civilians.

Of the 132 homicides of former FARC fighters currently being investigated by Colombia’s Dismantling Criminal Bands Unit, less than half have a suspect. Many of the ex-militants have died for not returning to the fight and for refusing to engage in illicit activities with criminal organizations. This unit was created by the peace treaty and has developed a holistic plan to protect and assist the integration of the demobilized combatants.

However, it’s unclear whether or not it will be able to hold the alleged assailants accountable, be they members of the Gulf Clan (a transnational crime organization), FARC dissidents, or the local police force. And, given the prevailing sense of impunity, more than 2,300 fighters have returned to armed struggle.

A little more than a year before the peace treaty was ratified, the retired chief of the national police, Oscar Naranjo, called on the Colombian business elite to take leadership on this issue. Naranjo, who was also part of Colombia’s negotiating team in Havana, knew that social inclusion could not succeed without economic opportunity. Since the treaty went into effect, Colombia’s economic growth has been weak, registering just 1.4 percent in 2017 and 2.7 percent in 2018. The stipend provided to former fighters is just three-fourths of the national minimum wage and promised seed capital for business ventures has been hampered by bureaucratic inefficiencies.

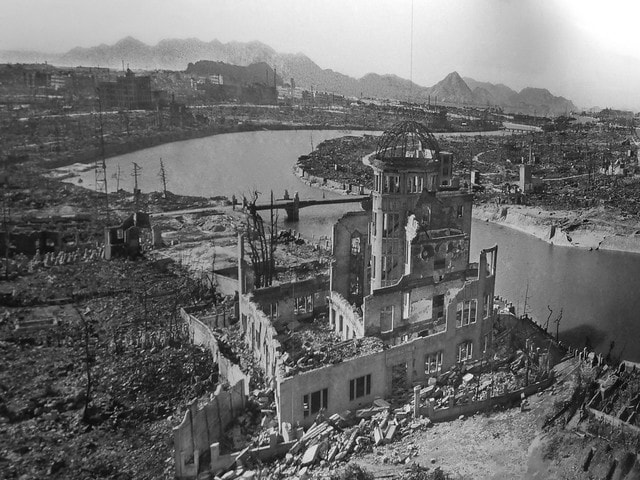

Photo Credit: Colombia’s Alto Comisionado para la Paz

It is the combination of these factors that present a clear and present danger to the peace process.

Yet, it is the success of the peace process that will give Colombia the space to confront its myriad of other challenges, including combatting increasing cocaine production, the human tragedy of Venezuelan refugees, and the general insecurity linked to organized crime and drug trafficking.

At the international level, the United Nations Security Council is united in its support of the peace process. President Duque has called for the United Nations to continue its monitoring of the peace process. The good offices of these institutions must continue to pressure President Duque into fully implementing the accord.

These institutions must provide advice and guidance when requested and deliver aid and support when needed. Norway earned the trust of the Colombian state and must use this credit to push for full implementation. The European Union must increase its vital support through its EU Trust Fund for Colombia, which has reincorporated ex-combatants into rural areas.

Regionally, the Organizations of American States Mission to Support the Peace Process (MAPP/OAS) in Colombia visited 720 rural villages at the end of 2018, beginning the process of connecting local bodies with national state institutions. Its chief of mission, Roberto Menéndez, continues to support the need for coordination between existing national and local government offices for the protection of social leaders and for a guarantee of the inclusion of affected populations.

The activism of Colombian politicians, peace campaigners, social leaders, and human rights activists have kept the issue of the accord alive despite the discouragement present in the broader Colombian body politic. This fight must continue and, evidenced by the marches for life, Colombians will continue to demand peace despite what Colombian Senator Roy Barrerras calls the “moral assassinations of the voices of peace.” Their courage and resilience must be supported emotionally, materially, and politically by the public and internationally.

The Colombian diaspora and NGO organizations also play a vital role in generating international support of the peace accord and demanding its full implementation. The solidarity marches are one example of the various strategies that must be deployed.

The peace dividend has already paid off in certain ways. It is not a coincidence that the 2018 elections were the most peaceful in living memory. The Truth Commission has begun its work and has been accepted by the affected parties.

Peace is as important for Colombia as it is for the world. And, since everyone has a stake in the outcome, the international community must engage and support the social leaders, human rights activists, and peace campaigners fighting for peace in Colombia.