Not enough time is given to reporting on climate change compared to other news, and that’s a fact. Newsrooms around the world are currently in the grips of Ukraine war news, as they should be, yet climate change will not go away and still requires our attention: After all, it concerns our very existence on this planet.

As German media DW recently pointed out: On any given day of the average 38 stories on their home page, only one or two are about climate change. What is true for DW is true for any other major media outlet — and DW is no climate denier, far from it, it actively supports the fight against climate change, including through a special series of videos available on Youtube, the Planet A series focused on sustainability and climate change issues.

A couple of days ago, DW released its latest video in that series: It carries the provoking title “It’s hard to care about climate change.” To drive the point home, the video opens with an arresting calculation: When Amazon billionaire Jeff Bezos went up in space last year, US news networks dedicated 212 minutes to the event in one day while climate change for the whole year occupied 267 minutes. In short, climate change’s coverage was about 350 times less than what Bezos got for his pleasure trip in space.

So, yes, we have a very big problem with climate reporting: Climate change is simply not getting the attention it should.

John Mecklin, the editor-in-chief of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists made that point forcefully in an interview last week with Covering Climate Now (CCN): “Yes, other issues are important, but if we don’t pay attention to the existential issues first, there won’t be a civilization for those other issues to play themselves out in.” (bold added)

Climate reporting, despite this, is alive and well. For example, CCN is a very active network of journalists reporting on climate change (including Impakter), founded in 2019 by the Columbia Journalism Review together with The Nation, The Guardian and WNYC; it has now 460-plus partners in 57 countries featuring some of the biggest names in news, including three of the world’s biggest news agencies — Reuters, Bloomberg, and Agence France Presse.

Recently CCN has organized several special events for its members to draw attention to the problems of climate reporting. The events focused on the pressing question: What can journalists do, how can they write about climate change in a way that attracts the readers’ attention, that gets them involved and places the issue where it should be, at the forefront of all the news? And what happens when there is an urgent, heartbreaking issue like the war in Ukraine?

These are the questions that CCN tried to answer a few days ago through a webinar intriguingly titled “War, Oil and Crimes: Reporting the New Climate Story.” Moderated by Mark Hertsgaard, CCNow’s executive director and environment correspondent at The Nation, the webinar featured three notable panelists: Nathaniel Bullard, Chief Content Officer at BloombergNEF, Naomi Klein, Senior Correspondent at The Intercept and author of several bestsellers (This Changes Everything; The Shock Doctrine; No Logo; On Fire) and Sammy Roth, Energy Reporter for the Los Angeles Times. It is worth taking the time to watch, click here to see it.

CCN is not alone in the field, trying to improve climate reporting. Most responsible major media run video series on the climate and along with DW, you will find the BBC, France 24, PBS, The Guardian, The Economist, National Geographic, AlJazeera, and many more. YouTube carries numerous video series on climate that are worth checking.

For specific questions and information, the go-to site is the award-winning MIT Climate Podcast portal that breaks down the science, technologies, and policies behind climate change, how it’s impacting us, and what we can do about it. Each quick episode cuts through the jargon to give you the what, why, and how on climate change — from real scientists and experts — with the goal of helping us make informed decisions for our future.

A paradigm change in the main message carried by climate reporting: It’s not too late to address climate change!

On February 17, CCNow held a joint press briefing with Scientific American on a little-known scientific development that carries paradigm-shifting implications for how people think and feel about the climate crisis and how governments and societies respond to it.

Most climate reporting has long echoed what journalists believed was the scientific consensus: Even if greenhouse gas emissions stop, global temperatures will keep rising for 30 to 40 more years, mainly because of carbon dioxide’s long lifetime in the atmosphere.

But it turns out this is wrong, in fact, the latest science doesn’t say that at all. And journalists reporting on climate change hadn’t realized the change in climate science or its implications. Perhaps this should surprise no one, after all, the issue is a complex one with many threads. Let’s try to unravel it.

Host Raya Salter, a climate lawyer, recently spoke to MarkHertsgaard, a veteran climate reporter, author and Executive Director of CoveringClimateNow, about this “hidden science” and what it means for the climate movement.

The lag time for a temperature rise is not 30 to 40 more years no matter what we do — a thought that instills in anyone an immediate sense of helplessness, of doom and gloom — but that lag time is in fact likely to be ten times less if we start acting now.

That’s what the latest climate models show; leading scientists like Michael E. Mann have dramatically revised that lag time estimate down to as little as three to five years.

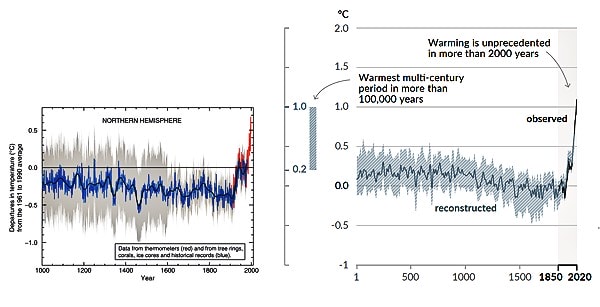

Michael Mann is someone we should listen to: He is one of the world’s most influential climatologists, famous for co-authoring the “hockey-stick graph” which showed the sharp rise in global temperatures since the industrial age for the first time. Published in 1998, it served to illustrate the conclusions of the IPCC.

The graph was a pioneering attempt to put together data from hundreds of studies of past temperature using “proxies” from analysing things like tree rings, lake sediments and ice cores. Here are both graphs, the original in 1998 and the latest in 2021:

The above pair of graphs tell the same story, except now the hockey blade is longer and sharper. As Mann wrote, referring to the IPCC report issued in August 2021: “As the new IPCC report lays bare, we are engaged in a truly unprecedented and fundamentally dangerous experiment with our planet.”

The change in time lag was a major point highlighted in the IPCC report mentioned above, yet, some eight months later, the point still hasn’t sunk in. Even though it is what scientists have now been saying for several years, as was fully explained in a major (and very clear) Scientific American article published last October.

That article carried the telling title: “There’s Still Time to Fix Climate—About 11 Years” and the subtitle left readers in no doubt as to what needs to be done: “Aggressive policies enacted now can extend the deadline and prevent the worst catastrophes.”

The next IPCC report, just released three weeks ago, on February 28, confirmed that time was running out on us, but with a major proviso: It was running out only if we continued to do nothing, basking in promises not held.

Journalists around the world rushed to report on it — as they should and as we did too here at Impakter. We highlighted, inter alia, the IPCC’s call to pay more attention to the Global South, as it is most directly affected by climate change and requires urgent action.

But — bad luck — the Ukraine war quickly overshadowed the IPCC report in the news cycle.

Climate reporting’s two biggest problems: The immediacy of issues like war, natural disasters and pandemics and the need to provide “balanced reporting”

The war is immediate, the war hurts, there is no escaping it, directly or indirectly. Pandemics as we sadly learned with Covid not only kill but can change everyone’s life, causing job losses, massive economic disruption and deep physical and psychological damage. As to natural disasters, volcanic eruptions, earthquakes and tsunamis, we have all seen with horror the images on our screens.

Climate change, in contrast, appears as a distant threat, embodied now and then with the news of wildfires and sudden floods which places it among natural disasters, a class of issues we are familiar with and that has stopped scaring us (it always appears to happen to someone else). And yet, unlike your run-of-the-mill natural disaster limited to a specific location, climate change is a global natural disaster and that change in scale makes it something entirely different and new.

Despite this overwhelming and scary fact that should place climate change, by all rights, at the front of the news, it’s not happening. Why?

Climate reporting faces two basic challenges: one, as humans, we instinctively respond to immediate dangers. Perhaps the most famous social scientist of our time, Daniel Kahneman who received the 2002 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences for his pioneering work with Amos Tversky on decision-making, exploring this “short-termism” issue that afflicts us all, said it best in his best-seller “Thinking Fast and Slow”:

“Our comforting conviction that the world makes sense rests on a secure foundation: our almost unlimited ability to ignore our ignorance.”

It’s hard for us to be aroused by long-term issues and our politicians know this well. Our political systems are built on short-term agenda, and even the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals — the longest political agenda anywhere — covers only 15 years, ending in 2030. With the expectation of course, that it will be renewed.

Aside from short-termism, the other challenge afflicting climate reporting and muddying its message is the need for balanced reporting.

There is always someone somewhere voicing a contrary view. And it can even be found among the academic community although 99% of scientists agree that climate change is taking place. There is always that loud one percent of climate deniers that is given far more space than it deserves in the news because too many newsrooms are still guided by the principle of “balanced reporting,” i.e., giving equal space to contrary views.

And we all know who’s behind (and paying for) the contrary view. The DW video above shows us flashes of BP and Exxon, but here we’ll call a spade a spade: It’s the fossil fuels industry, acting precisely as the tobacco industry did 40 years ago, paying scientists to come up with the results desired by oil and gas managers and investors. This kind of fake science should have no place at all in climate reporting.

Even the global panel of scientists informing us and guiding us through the climate crisis, the IPCC, is not immune from “pollution” caused by climate deniers.

Over the years, there have been several scandals, with ugly email exchanges leaked to the press, accusations of data manipulation and the like that have not helped the IPCC’s message or standing in the eyes of the public. The latest? It concerns the denialist physicist Taishi Sugiyama, research director of the Canon Institute for Global Studies (CIGS) and Japanese government expert who collaborates with the IPCC since AR4, i.e., since the 2007 Climate Report. According to Spanish journalists who reported on this, Sugiyama flatly denies the climate crisis, demonizes decarbonization and calls Greta Thunberg a communist:

Esto que cuento hoy en @LMClimatica, especialmente el caso del negacionista Taishi Sugiyama, es un escándalo inadmisible. Las conclusiones de los informes del IPCC pueden no estar en duda, pero que haya gente así dentro lanza un mensaje muy peligroso. https://t.co/kBi2g4EynB

— Eduardo Robayna 🔻🌎 (@EduRobayna) March 16, 2022

To sum up: There is an urgent need to call a spade a spade, stop giving equal time to climate deniers and focus instead on the positive side, giving more space to climate solutions.

As the New York Times recently pointed out, there is “a growing chorus of young people” focusing on climate solutions. One of the young sustainability scientists interviewed by the Times, Alaina Wood, 25, who shares her climate messages on Tik Tok said: “People are almost tired of hearing how bad it is; the narrative needs to move onto solutions.”

Indeed, that is the way forward: Less doom and gloom, more solutions.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: A climate denier’s message goes under water Source: Matt Brown, Flickr.