Twelve years ago, in an effort to curb rising emissions, high income countries promised to provide $100 billion in climate finance every year by 2020 to low income countries. On Monday, they admitted they hadn’t reached this goal and wouldn’t until 2023. Meanwhile low income countries have been forced to foot the bill of a crisis they largely did not create.

Climate finance represents a key tenet of climate action. It laid the foundation for cooperation and trust. It acknowledged the inequality imbued in the climate crisis; poor countries have contributed the least but will suffer the most. Despite its significance, climate finance has been failing for over a decade.

The system needs revision, accountability and a large financial boost. Over recent years the system has come under criticism for overestimating its success and failing to address the needs of “developing countries.” The system has prioritised mitigation over adaptation, created climate debt traps and reduced the net flow of aid to countries in need.

Recipient countries have been stripped of autonomy as benefactors decide where funding is allocated. The prioritisation of mitigation projects such as investments in renewables over adaptation projects has allowed “benefactors” to make a profit whilst denying vulnerable communities of much needed funds to cope with the reality of the climate crisis.

Almost 100 million people were affected by climate-related disasters in 2020, over 15,000 died and at least $171 billion was lost. In rural Bangladesh, poor families spend almost $2 billion a year preventing or repairing damage from climate-related disasters. This is 12 times more than the entire country receives in multilateral international climate financing. The average person in Bangladesh emits 24 times less carbon dioxide than the average American.

The expenses are only set to increase. Annual adaptation costs in developing countries will reach $140-300 billion by 2030 and $280-500 billion by 2050, according to the UN Environment Program (UNEP). These countries can’t shoulder this burden by themselves nor can they wait as climate change already threatens the status and inhabitability of nations like the Marshall Islands.

“Climate-vulnerable and financially stressed nations do not have the luxury of waiting one, two, or more years to access the limited funds that are available. Simpler and faster processes are urgent.”

–said Costa Rican President Carlos Alvarado Quesada

A broken system

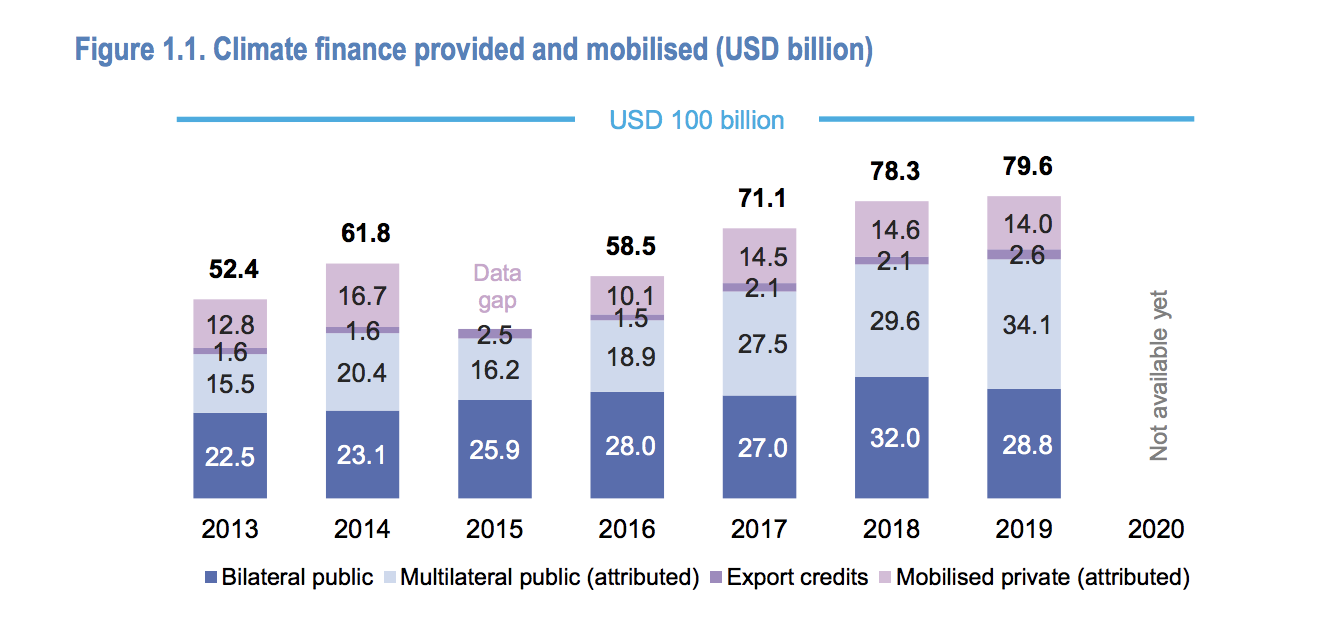

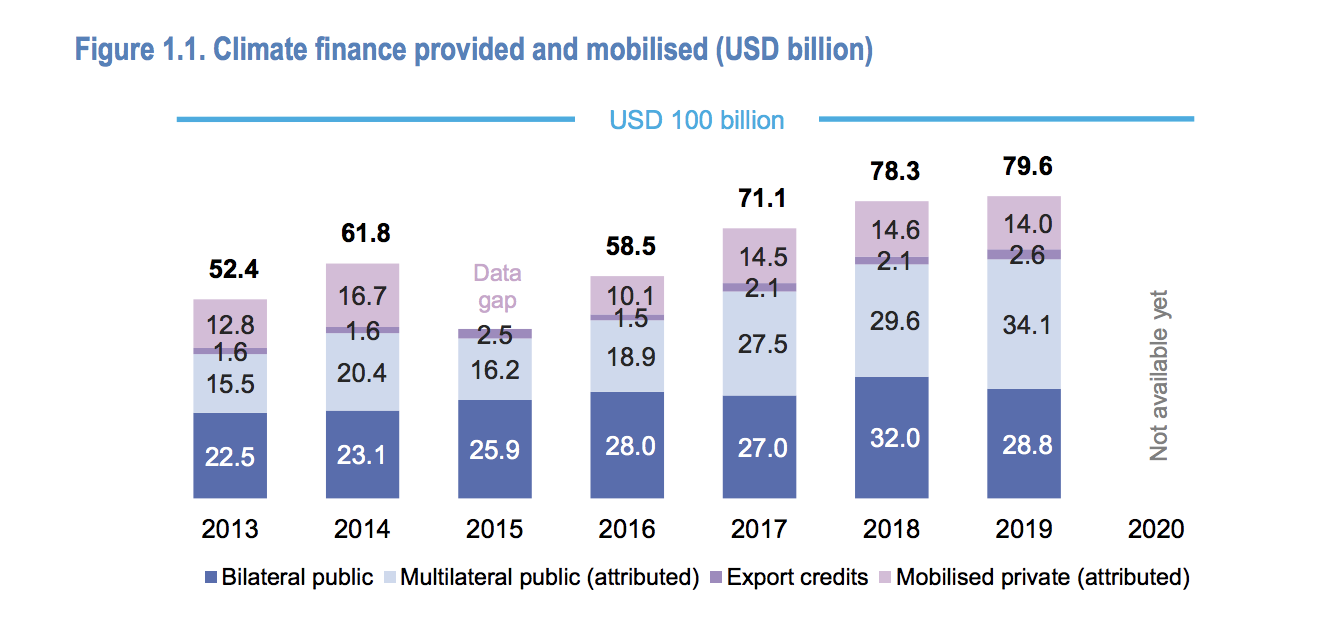

High income countries promised $100 billion per year. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), they delivered $80 billion at best. In real terms though, only $59.7 billion was received as 80% of public climate finance came in the form of loans; at least half of which required higher repayments from poor countries potentially pushing already-vulnerable countries into climate debt traps.

Not only are poor countries having to go into debt because of climate finance, they’re also missing out on Official Development Aid. Countries are merging foreign aid with climate finance which means they’re either unduly taking credit for climate action or climate finance is eating into resources intended to help poorer countries develop. Either way, it’s unethical for the scarce resources directed to poverty reduction to be appropriated to fix a problem created by wealthy nations.

It’s clear the system needs to be revised and leaders are aware that climate finance will be a key sticking point at the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26), which convenes in less than a week. Climate action was largely predicated on the idea that financial and technical assistance would be provided and that countries would remain true to their promises. As these promises have fallen through, the trust that props up climate action has eroded.

A shiny new plan to save the day

Despite missing the $100 billion target — even by inflated accounting standards — leaders hope that a new climate finance delivery plan can restore lost faith. Earlier this year German and Canadian climate ministers were assigned to close the funding gap. Together they produced a new climate finance delivery plan which promises to:

- Increase the scale of climate finance

- Increase finance for adaptation

- Prioritise grant-based finance for the poorest and most vulnerable

- Address barriers in accessing climate finance Strengthening the Financial Mechanism of UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement Working with MDBs to increase and improve climate finance

- Improve the effectiveness of private finance mobilized

- Report on collective progress transparently

- Assess and build on lessons learned

- Take into account the broader financial transition needed to implement Article 2.1(c) of the Paris Agreement

Disappointingly the report seems to repeat the mistakes of the current system; it fails to provide key targets and accountability measures. These improvements also risk having little effect if a massive injection on funding is not provided soon.

In recent months, countries such as the United States and Canada have updated their pledges, doubling the amount of climate finance they will provide. These amounts still mean relatively little though in terms of the economic toll of the climate crisis and the historical responsibility of these countries.

Related Articles: Africa Calls for Climate Finance Reform as Pledges Go Unmet | Can the Paris Agreement Goals Be Met? How The Global Stocktake Works

How much does climate change cost?

The $100 billion figure is largely symbolic. It was not developed based on liability or compensation needs. If it were, the figure would be a lot higher. Under conservative assumptions, the carbon liability of the world is $34.2 trillion, or around 40% of world GNI.

The collective liability of OECD countries (which broadly align with the “developed countries” in the $100 billion agreement) is about 44% of the total at $15.2 trillion.

OECD countries have inflicted $15 trillion in damages through carbon emissions alone. If they were to pay this off annually until 2100, it would amount to $190 billion per year, double current climate finance pledges. It’s clear that high income countries are obligated to provide a lot more than they currently are.

Richer nations have reaped the benefits of untrammelled pollution for generations, often at the expense of developing countries. As those countries now try to grow their economies in a clean, green and sustainable way we have a duty to support them in doing so – with our technology, with our expertise and with the money we have promised.

-UK prime minister Boris Johnson said in a speech at the UN in September

This money needs to be mobilised, and it can be. In 2020, almost $2 trillion was spent on the military, over $5 trillion was used to subsidise fossil fuels and $16 trillion was provided in Covid stimulus measures.

“The economic impact of COVID has been significant but temporary. The GDP impacts of climate, however, are permanent, long-term and grow larger with each year of inaction,” said Claire Ibrahim, a director at Deloitte Access Economics. Climate impacts are projected to cost the world economy $7.9 trillion by 2050.

Economists are resolute, when it comes to the climate crisis, the costs of inaction vastly outweigh the costs of action. The original Stern Review was clear on this when it was published in 2006; the updated version released October 26. is even more adamant. Meeting the Paris Agreement goal of net-zero carbon emissions requires investments worth 2-3% of global output every year until 2050. However, a business-as-usual trajectory would lead to a 2.4 degree rise in global temperatures and global loss in economic output of 10%.

Action wouldn’t just safeguard the global economy from losses, it could bring in $26 trillion in economic benefits by 2030 according to some estimates.

Success at COP26 depends on climate finance

“The pandemic has shown that countries can swiftly mobilize trillions of dollars to respond to an emergency — it is clearly a question of political will,” said Nafkote Dabi, Oxfam International’s Global Climate Policy Lead. Dabi went on:

Let’s be clear, we are in a climate emergency. It is wreaking havoc across the globe and requires the same decisiveness and urgency. Millions of people from Senegal to Guatemala have already lost their homes, livelihoods and loved ones because of turbo-charged storms and chronic droughts, caused by a climate crisis they did little to cause. Wealthy nations must live up to their promise made twelve years ago and put their money where their mouths are. We need to see real funding increases now.

COP26 represents one of humanity’s last chances to avoid catastrophic global warming. This chance is undermined by broken promises and pledges. Few countries are on track to meet their emissions reduction targets and even if all 2030 climate pledges are met, the planet will still heat up by 2.7 degrees by the end of the century. COP26 must result in decisive and collective action, but the cooperation necessary is reliant on trust. Poor countries must be able to trust that rich countries will provide the necessary financial and technical assistance.

For too long, high income countries have lived at the ecological expense of low income countries. As these countries battle the realities of a climate crisis they did little to contribute to, large swathes of money need to be mobilised. The current climate finance flows are not enough. The new climate finance delivery plan is not enough. The system needs to be overhauled and if it isn’t, it’s unlikely COP26 will bring forth the decisive action needed to save our planet.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: Sign reading “System Change Not Climate Change.” Featured Photo credit: Ma Ti