When Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi was ousted by a blitzkrieg in 2011, three European countries played a key role, the UK, France and Italy. With America “leading from behind”, a polite way to say that America provided only military support while the Europeans called all the political shots.

This time, as Libya descends again in the chaos of war, the situation is different. With the UK in the grip of Brexit, only two European powers remain in play, France and Italy. But they are embroiled in a series of diplomatic spats, and their rivalry in Libya has deep roots, as Impakter Italia explains in a recent article reproduced here. Impakter Italia, launched with an editorial on April 13, 2019 is Impakter’s sister publication in Italy, sharing a common vision and mission.

First, a quick update on the current situation. Libya today is divided between two rival governments: one in the eastern city of Tobruk backed by strongman Khalifa Haftar and an internationally-recognised Government of National Accord (GNA) based in Tripoli. Haftar has forged close ties with a branch of Salafists, called Madkhalists, using their fighters and incorporating their conservative ideology in the parts of eastern Libya he controls, including a ban on women travelling without a male guardian.

On 4 April, as UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres was in Tripoli to help organize a national reconciliation conference planned for mid-April, Haftar audaciously launched an assault on the Libyan capital with his self-styled Libyan National Army (LNA). The LNA was pushed back at Checkpoint 27 – also called “Gate 27” – on the coastal road between Tripoli and Zawiya, some 45 kilometres west of the Libyan capital. 120 LNA fighters were taken prisoners.

But the setback was only temporary and the battles rage on, with the outcome still uncertain and Haftar pushing forward:

This week, while Notre Dame was burning in Paris, Italian Prime Minister Conte was sounding the alarm in Rome about an impending humanitarian crisis in Libya. “We are very worried about the Libyan crisis”, he said, “we have always worked and will continue to work to avert a humanitarian crisis that can expose us to the risk of the arrival of foreign fighters in our country.” He was referring to the reported 400 ISIS prisoners in Libya that could now escape as war is spreading. And he concluded: “We absolutely must avoid escalation”.

Yet Italy cannot solve the problem alone. Populist leader and Interior Minister Salvini insists that his policy of keeping Italian ports closed to ships bringing in refugees is working. The Italian Minister of Transport and Infrastructure, Danilo Toninelli, disagrees: “If thousands of asylum seekers arrive, the closed ports policy is not enough,” he said at Radio Anch’io, explaining that “other European ports will have to be opened” and “a redistribution of migrants will be needed “. Therefore, the minister underlined, “the approach must be international”. He meant: European.

How to avoid the threat to Europe – a new wave of migrants and possible terrorists among them – is going to require a concerted European action. But for now, that is not happening. Diplomatic tension between France and Italy has not abated and France has just announced that it will continue for another six months its policy of closed borders with Italy. Not exactly an example of European cooperation.

To help understand how two major EU member countries, like Italy and France, that should work closely together, yet do not do so, Eduardo Lubrano’s article on Impakter Italia throws much needed light:

Why France and Italy are competing in Libya

by Eduardo Lubrano

Eight years after Gaddafi’s death, Libya is still in the midst of a civil war. On the one hand the forces of Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar, the leader of the Libyan national army (NLA). On the other hand, the legitimate government, supported by the UN, in Tripoli, led by Prime Minister Fayez al-Serraj.

Why the war in Libya is a cause of tension between Italy and France

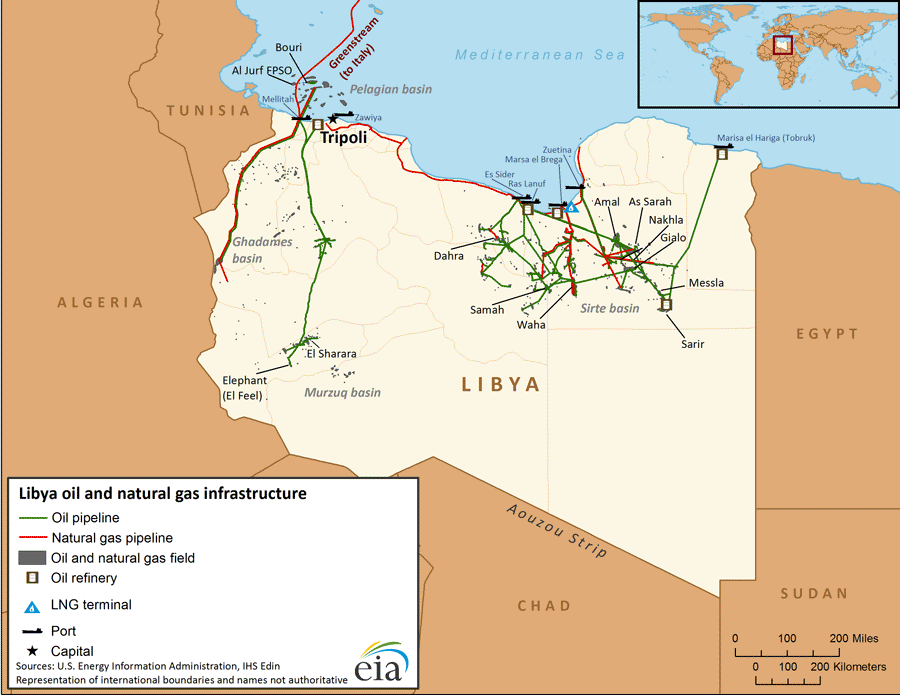

The key word is: oil. Deposits, installations, factories. In the south of the country, in the Fezzan region.

The Al-Sharara oil field, 700 kilometers south of Tripoli, produces a third of Libyan oil. Here is a joint venture between the Libyan state company National oil corporation (Noc) and four companies Repsol (Spain), Total (France), Omv (Austria) and Equinor (Norway). A little further south is the El Feel or Elephant field managed by the company Mellitah Oil and Gas, a 50/50 joint venture between the Italian Eni and the Libyan Noc.

Those who control these areas militarily have an extraordinary economic strength in their hands.

Haftar, who was once Gaddafi’s right-hand man, has the support of Russia, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates and France: in 2017 he was saved from the deadly danger of a cerebral hemorrhage in the Val-de-Grace Hospital in Paris.

Al Serraj is instead supported by Italy and the United Nations, with the United States remaining for now neutral. At the beginning of the year some of his loyalists seem to have discouraged him with the accusation of not being able to guarantee either the security of the country or the political transition.

Not Only Oil for Italy

The Italian petroleum giant Eni has been in Libya continuously since 1959. Because oil is so plentiful and easy to extract, in 2017 production reached a record level of 384,000 barrels per day.

There is also the extractive potential of two new gas fields discovered in an area close to the Egyptian coast, fields that for Eni represent “the largest gas discovery ever made in the Mediterranean”.

In the video: On 16 March 2018, Eni Chief Executive Officer Claudio Descalzi discussed oil and gas exploration with Bloomberg’s Jonathan Ferro on “Bloomberg Markets: The Open.” He pointed out that ENI considers exploration as a “weapon against a difficult oil market”, a comment that explains the high level of ENI activities in politically unstable places like Libya.

Commercial links with Italy have deep roots. Consider that the Libya-Italy trade was 10 billion euros ten years ago, before the war that ousted Gefaffi.

France’s Views on Libya

French oil company Total CEO Patrick Pouyanné explains: “our group aims to strengthen our portfolio with high quality low-cost oil assets all the while consolidating our historical presence in the Middle East and North Africa”.

The strategy is clear: Libya is in an optimal position to gain control over the Sahara where the French presence is strong.

All this adds up to one of the greatest challenges for the European Union: How to align the geopolitical and economic interests of each Member State with the needs of a common European foreign policy.

Author: Eduardo Lubrano: Member of the Impakter Italia team. Professional journalist, expert in history, sports expert. He has collaborated with TG3, worked for Telepiù and works for La Repubblica. His articles published on Impakter Italia are listed here.

Featured Photo Credit: United Nations Photo/Flickr