With recent Chinese political propaganda and military drills aiming to stimulate a contentious attitude from the Chinese people, and tensions between China and the US aggravating due to the US’s support for Taiwan, the rise of China to power is a highly debated topic among schools of thought in global politics. However, the concept of power is broad enough to cause confusion on the topic. Within global politics, power is defined as the ability to control or influence the behavior of people and power exists in all social relationships between human beings. So, what is meant by China’s rise to power, is in reality, a question about China’s rise to regional hegemony.

Additionally, the debate doesn’t revolve around China’s rise to regional hegemony directly, but around the response, it might trigger in its neighbors and the USA, since, as stated by political theorist Joseph Nye, “war was caused nor merely by the rise of one power, but by the fear it engendered in another. The belief in the inevitability of conflict can become one of the main causes.”

What are the political theories?

Political theories, or political school of thoughts, are no more than theoretical perspectives for understanding global politics. Each school of thought has a different explanation of why states – or countries – behave the way they do.

Classical realism believes that there is an unchangeable human nature of being “power-hungry” which causes states to behave a certain way. Structural realism (also known as offensive realism and neorealism) argues that the very structure of the global political system – independent states under an anarchic system, with no power above the state – explains how states behave. And lastly, liberalism ( not to be confused with the way this term is used in domestic politics, meaning left or center) emphasizes how states are interdependent and always have their position within the international system in mind when deciding their next move.

Classical Realism

Classical realists, such as Kennan and Morgenthau, believe that when it comes to how China’s neighbors and the USA will react to China’s rise, the wisest strategy is to engage with China, and set up an environment with less tension as possible to avoid conflict. It is a shared belief amongst classical realism theorists that countries should be aware that “choices made by states are affected by what goes on inside of them, and choices made by states are also affected by the choices made by other states (Kirshner).”

In other words, for China’s rise to be peaceful, the nations involved need to be aware of the complexity of politics and place it before its own needs. Additionally, this argument sees two possible outcomes for China’s rise to power: (1) they will emerge as a responsible great power peacefully and be willing to engage in multilateral negotiations, or (2) it will be a disastrous bid for hegemony, which will most likely lead to armed conflict with the USA.

Kirshner, a classical realist scholar, also argues that the latter outcome wouldn’t be the wisest strategy for the United States, since an effort to slow China down would backfire for three main reasons: cost, harm to its international political position, and the possibility to increase even more China’s ambition.

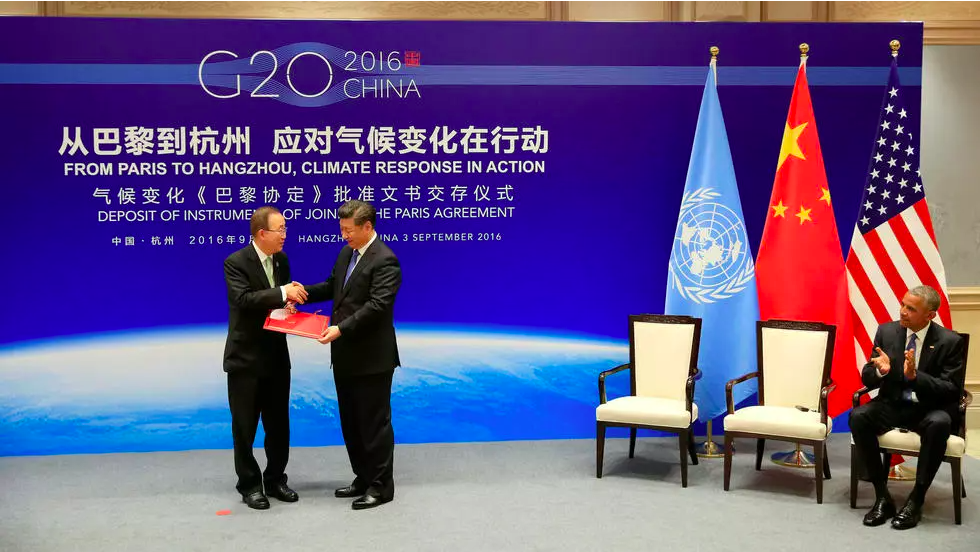

It is possible to trace such behaviors expected by classical realists in some of the state’s current actions: China has already been willing to engage in multilateral forums and agreements as it tries to convince its neighbors that its intentions are benign, and has also worked closely with the United States on Climate Change and played a pivotal role in the COP21 climate change agreement in Paris.

This backs up the classical realist’s argument since it shows how, already, China and the USA are choosing to engage rather than confront each other. However, since this argument is based around the expectancy of multilateral actions involving the USA, China, and it’s neighbors, this argument also ignores all of China’s unilateral investment on its hard and soft power, which outweighs the nation’s multilateral investment.

In other words, not only does the classical realist perspective of China’s rise to power rely on the expected future actions that might be taken by China, the USA, and its neighbors, but these expectations are also based on only a small part of these countries actions and completely ignore the many times they have conflicted rather than engaged with each other.

Structural Realism

Structural realists such as John Mearsheimer, believe that China will not rise peacefully. It is argued that China’s rise will lead the US and China to engage in an intense security competition with considerable potential for armed conflict and that most of China’s neighbors will join the US in this competition to contain China’s power. Mearsheimer explains this phenomenon by stating that “the mightiest states attempt to establish hegemony in their region of the world while making sure that no rival great power dominates another region.”

In their bid for regional hegemony, structural realists also believe that China will attempt to dominate Asia the same way the US-dominated the Western Hemisphere, which consequently means that China is likely to try and push the United States out of Asia.

Their argument is backed up by China’s investment in both its soft and hard power, which could mean that they are securing themselves on their run for hegemony against the USA. China’s investment in its soft power can be seen through the “Made in China 2025” initiative, where president Xi made it clear that he intends to overtake the US’s first place in world technology soon.

China’s investment in its hard power can be clearly seen with China’s actions on the South China sea. The disputed territory has competing claims by most of China’s neighbors: Vietnam, the Philippines, Taiwan, Malaysia, and Brunei. China has submitted a nine-dashed line that goes against UNCLOS agreements on how the territory should be divided.

China has also sent military bases to artificial islands in that region, which has sparked major tension in the area. China has also made it clear that it is not willing to negotiate about the region with ASEAN (an alliance made up of most of the countries that oppose the nine-dashed line).

Liberalism

Liberals like Joseph Nye believe that China’s rise will be peaceful, because there is no reason, at least not in this century, for the United States to feel threatened by China, and therefore there is no reason for the US, or any of China’s neighbors to resort to armed conflict.

They argue that it is more beneficial for China, America, and all of its neighbors for China’s rise to be peaceful than for it not to be. China has the second-largest economy in the world, but its income per capita is only $1,700 or one twenty-fifth that of the United States, and China’s research and development is only ten percent of the American level.

China is also America’s third-largest trade partner and China holds over two trillion dollars in foreign exchange reserves, most of which are in the form of US dollar assets, in particular, US government debt. The two later pieces of evidence support Liberal’s claim that it is more beneficial for China and the USA that the rise of China to power be peaceful since it shows that in many ways the countries depend on each other. But it also reflects one of the key concepts of liberalism – complex interdependence.

The concept of complex interdependence explains that states interact and depend on each other through multiple channels and on multiple issues, which leads to a decline in the use and effectiveness of the military force. Therefore, liberals believe that the USA and China know that it is better for China’s rise to be peaceful since the two countries depend on each other in many ways, and the cost of an unpeaceful confrontation that could break this complex interdependence outweighs its benefits.

This argument is predicated on a delicate balance between being optimistic and realistic about China’s current and future situation. It is the only theory mentioned in this article that really takes in the human nature side of things that aims for survival but in less instinctive terms. It takes into account the fact that a peaceful rise to power doesn’t necessarily mean that one state is successful in suppressing the other. It illustrates how a peaceful rise can mean that both parties involved have an awareness of the dangers and disadvantages of armed conflict and choose not to let rushed assumptions about the possible intentions of other states lead them to armed conflict.

Which theory is correct?

Neither, and all. The explanation behind a state’s actions can be studied and theoretically explained but the accuracy of its prediction is almost impossible to measure. Just like experiments in the exact sciences, political theories try to examine the behavior of the political world, and with this information piece together possible ways it might behave in the future.

However, global politics is not an exact science, but rather a complex series of patterns of state’s behaviors. So far, China’s rise has been proven to be peaceful, but the possibilities for its rise to power, both peacefully and non-peacefully, are endless.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com.

In the featured image: Chinese soldiers with flags during the military parade/ Beijing, China, Sept. 3, 2015. Credits: AP photo by Ng Han Guan.