SERIES TITLE: Pipe dream or achievable vision: How can we deliver on the 2030 Agenda? The 2030 Agenda foresees a bright future for humanity, one in which everyone enjoys peace and prosperity on a bountiful planet. But, with nationalism, populism and protectionism on the rise, how can we deliver on this utopian vision? This series of articles looks at what the international development system needs to do to deliver on this incredibly complex task – from rebuilding trust in multilateralism to bringing in the trillions of dollars needed each year to finance change. The first article of the series can be found here.

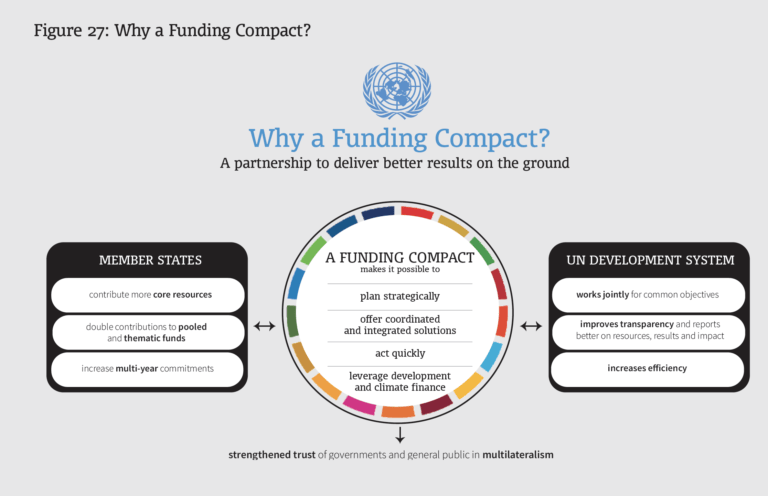

In my last 2030: Dream or Reality article I discussed how the current UN development system (UNDS) reform calls for a more flexible and integrated business model in order to achieve the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. As the implementation of the new Funding Compact, a set of multilateral commitments between the UNDS and its Member States, are at the core of this reform, I will discuss this matter more in detail in this article.

Quality, quantity and stability: these three words are at the core of the new Funding Compact. Quality refers to the type of funding needed — primarily core funding and flexible pooled funds that enable the UN to more efficiently and nimbly allocate resources. Quantity refers to the need for an increase in resources, particularly as the April 2, 2019 Report of the UN Secretary General states, in “substantial, up-front investment from Member States.” Finally, stability refers to the predictability of financing that comes from multi-year funding agreements. No more ad-hoc funding restricted to small projects, the UN is moving to consistent, pooled resources that can flow into strategic, objective-based initiatives. In turn, quality, quantity and stability can also refer to the increased coherency, transparency, efficiency, and above all results, which are the prime aims of the compact.

Such shifts [in behaviour] are interdependent and mutually reinforcing: progress on each side enables progress on all.

— Report of the UN Secretary-General

The changes required by the Funding Compact are by no means small or easy to execute. The same April 2, 2019 Report of the UN Secretary General declares that, “the funding compact must be bold” and achieving the SDGs will require “a fundamental shift in behaviour.” This boldness and behavioural change is called for on both sides of the agreement. By nature, “Such shifts are interdependent and mutually reinforcing: progress on each side enables progress on all.”

That said, considering that we are now in the season of New Year’s resolutions, perhaps the old adage “old habits die hard,” is ringing fresh in everyone’s ears. Now imagine trying to simultaneously reverse the 70+ year-old habits of a complex intergovernmental system of institutions and those of its donors — 193 different governments with all their own complex institutional settings. The trend toward strongly earmarked funding in the UN development system has been substantively growing since the 1990s. Is the Funding Compact really bold enough to reverse this ingrained trend? Furthermore, are the behavioral changes it requires drastic enough to reach our shared SDG goals and targets by 2030?

Overview of the Funding Compact

Before answering these questions, let’s take a quick look at what the Funding Compact entails. Overall the Funding Compact consists of eight commitments from Member States, and 13 commitments from UNDS entities, each with clearly defined (or soon-to-be defined) indicators to measure progress. A detailed explanation of these commitments and their indicators can be read online, but here is a brief summary for your perusal:

Commitments From Member States

- To align funding to entity requirements by increasing core funding to UN entities and the UN Development System (UNDS) to 30%, doubling the share of total contributions to UN inter-agency pooled funds to 10%, and doubling contributions to single-agency thematic funds by 2023.

- To provide stability by broadening funding sources to the UNDS, providing predictable funding to UN Sustainable Development Group entities and to the UN Development Assistance Framework at the country level; and providing adequate, predictable and sustainable funding to the resident coordinator system budget.

- To facilitate coherency and efficiency by supporting the implementation of efficiency measures (as measured through a 100% cover of the cost of common premises by additional financial and/or in kind contributions), and fully complying with cost-recovery rates.

Commitments From UN Entities

- To accelerate results on the ground through enhanced cooperation for results at the country level, increased collaboration on joint and independent system-wide evaluation products, and the implementation of the new resident coordinator system.

- To improve transparency and accountability by improving reporting on results to host Governments, presenting clear funding frameworks for each UN Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework; improving the clarity of entity-specific strategic plans, integrated results, resource frameworks and their annual reporting on results against expenditures; strengthening entity and system-wide transparency and reporting, linking resources to SDG results; improving the quality and utility of Cooperation Framework evaluations; increasing the accessibility of corporate evaluations and internal audit reports; and increasing the visibility of results from voluntary core contributions, pooled and thematic funds and programme country contributions.

- To increase efficiency by implementing the Secretary-General’s goals on operational consolidation for efficiency gains; fully implementing and reporting on approved cost-recovery policies and rates; improving the compatibility of cost classifications and definitions, and enabling greater transparency across time and between UN Sustainable Development Group entities; and increasing the efficiency and effectiveness of development-related inter-agency pooled funds.

An even more simplified overview of the compact can be seen in the table below.

The Elephants in the Room

When debating the merits and weaknesses of the Funding Compact, one could get into the fine print and dissect whether or not the indicators for each of the above commitments are achievable and/or if achieved whether or not they will be enough. Certainly those debates will happen, and they should. But more importantly: at this initial roll-out phase of the Funding Compact, I think we need to draw attention to the two big elephants in the room: 1) The Funding Compact is a voluntary, non-binding agreement; and 2) The private sector is entirely missing from the Compact’s scope.

First of all, because of the voluntary nature of the Funding Compact, donors can still choose to contribute heavily restrictive earmarked funds to the UN Development System, albeit with a 1% coordination levy to offset the increased transition and administrative costs and other drawbacks of this type of funding. Ideally, the Funding Compact’s 1% levy is not merely a means of compensating for the fragmentation caused by earmarking, but as Silke Weinlich and Bruce Jenks put it in a recent article on UN system-wide finance, it “transforms the weaknesses of fragmentation at the entity level into a strategic asset at the system level.”

That said, if drastic behavioural change is required, is an opt-in, opt-out-as-needed model really the best means to achieve that? On the one hand, the voluntary nature of the Funding Compact enables Member States to change their behaviour at the pace and in the ways they are realistically able, without undermining the overall agreements. On the other hand, is the entire Funding Compact perhaps relying too heavily on mutually reinforcing actions that are incentive-based? So, if either Member States or the UNDS fall short of their goals or struggle to meet their end of the bargain, a negative snowball effect could ensue.

Related Articles: Silos Are for Farming, Not for Funding | Money Begets Money: Catalytic and Spin-off Effects of Two Flexible Financial Mechanisms

The accelerated increases of transparency promised by the UN could be used as an example of how this negative snowball effect could take place. These increases require a simultaneous commitment from Member States to streamline and harmonize reporting and visibility requirements while the UN addresses any gaps, inconsistencies and weaknesses in both entity-specific and system-wide efforts to improve transparency, visibility, reporting and evaluations. Any delays or impediments on either side in progress toward these goals, could hinder the progress on the other side: costly and complex reporting requirements could keep the UN from effectively increasing transparency, and slow or incomplete implementation of better transparency practices could demotivate Member States to voluntarily contribute core funds. In other words, the Funding Compact is perhaps still too vulnerable to bureaucracy and too unstructured in what the various sides of the agreement entail.

Secondly, if the Funding Compact is to be truly bold and transformative, it is without question that private sources of development funding need to be considered and involved. As is, the Funding Compact is not even targeting enough funding to cover the institutional and programmatic architecture necessary to achieve the SDGs. In order to make a realistic strike towards the 2030 goals, we need big financing and big flows — and we need them fast. This means strategically tapping into the giant resources of private business financing. This idea is not new, by any means. For example, the meetings coverage of a 2017 UN General Assembly session noted, “Lise Kingo, Executive Director of the United Nations Global Compact, said attaining the Sustainable Development Goals meant scaling up on alliances and partnerships, especially with the private sector… putting markets to work for sustainable development — would be a critical transformation in development planning.” Also, private business and industrial investments are specifically mentioned in the 2030 Agenda’s Addis Ababa Action Agenda. Yet, why then is the private sector still not integral to the global development finance Compact?

Here is another way of stating the obvious: In a world where according to the 2018 World Inequality Report, “Public wealth has declined in most countries since the 1980s” and, “A general rise in the ratio between net private wealth and national income has been observed in nearly all countries in recent decades,” how can the UN and its Member States afford a funding compact that doesn’t include the private sector?

In order to achieve dramatic acceleration, innovation and results on the ground, we still need to establish a more structured global multi-stakeholder compact, one that is truly bold and indeed binding.

These are some of the vital questions we need to be asking as we tackle the bigger question of “So, where do we go from here?” The new Funding Compact is a move in the right direction, but it may be a move that is only good for prolonging the status quo: progress, yes, but insufficient progress toward the 2030 Agenda. In order to achieve dramatic acceleration, innovation and results on the ground, we still need to establish a more structured global multi-stakeholder compact, one that is truly bold and indeed binding.