I still get lost in New York. I will probably still always get lost in New York. Because it is a gigantic city, but also because I have a terrible sense of direction that even my phone GPS can’t rectify. This city is a magical place. With a great deal of diversity, livelihood, and richness, it is undoubtedly a melting pot of cultures, languages, religions, cuisines, and most certainly, hungry, mucky rodents. When visiting New York, you will most likely be blown away by the incessantly busy streets, the enormous skyscrapers, and the boisterous surroundings that will keep distracting your eyes and ears until you eventually walk into someone, or in other less fortunate scenarios, a pole.

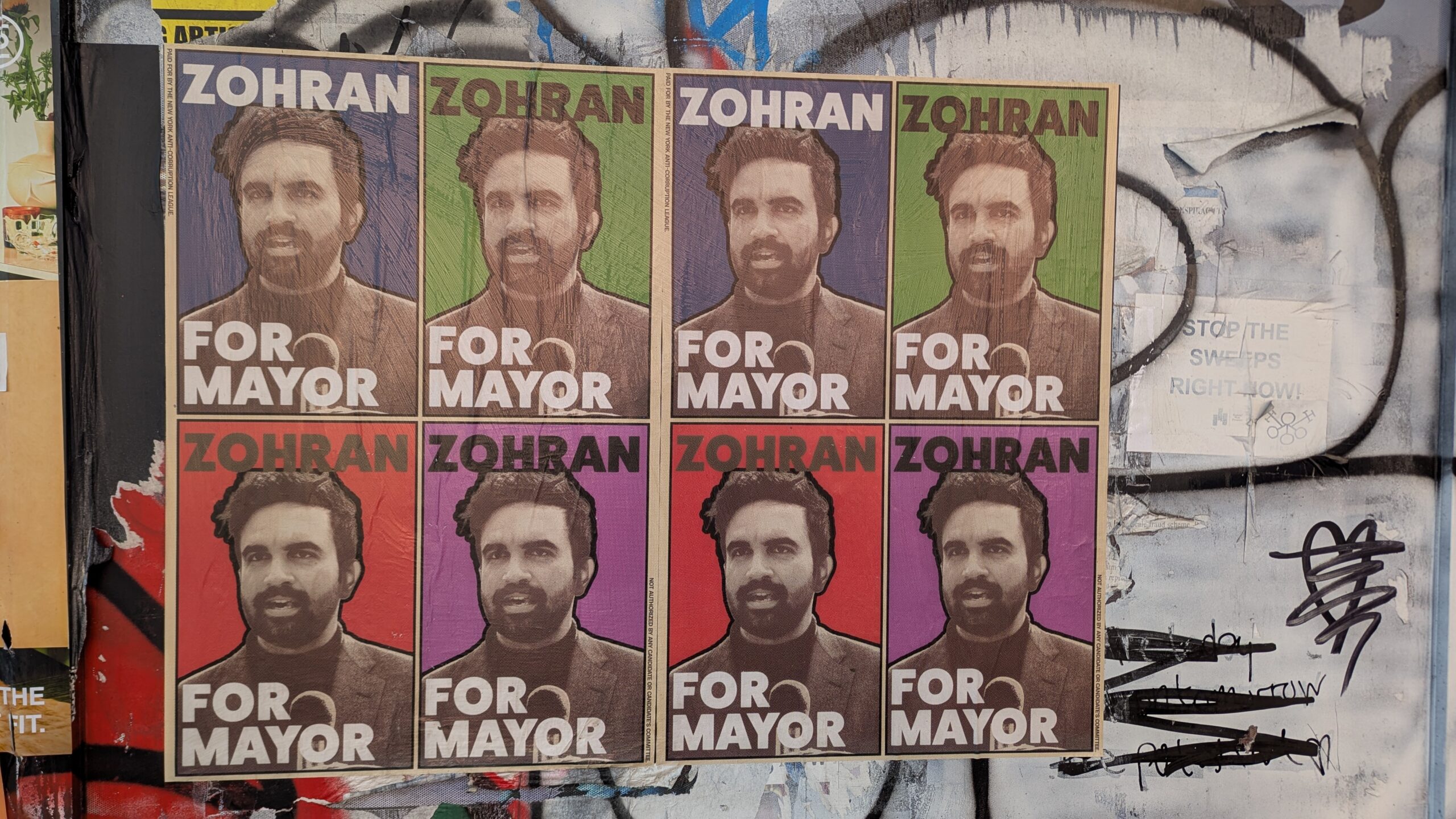

New York is a welcoming place. It enlivens me to be able to practice my rusty Russian with my barber, order my empanadas in Spanish from the Colombian lady across the street, or talk about Salvini being photobombed by a same-sex kiss with my two great Italian friends. In New York I love the richness of every encounter. Every meeting has a meaning. And every person has a story. A story that perhaps no more than that person knows. A story that, somehow, led that person to become an indispensable part of the cultural diversity that makes this city unique, glamorous, and special. Everyone contributes to making this place harmonious and diverse.

One might say that cities like New York, London, or Berlin tend to be significantly tolerant towards cultural minorities because they are fundamentally comprised of people from all over the place and are ran by progressive governments. And that statement is true, at least to some extent. To better understand the nature of human interactions in a megalopolis such as New York, we must think about the stories that make up what we can summarize in “cultural diversity”. We must learn about the individual stories that might have started in Delhi, passed by Tehran, traveled through Paris, and stopped by Caracas. These are the stories of which a city’s cultural diversity feeds off. The stories that almost no one ever hears of, because they are hidden under never-ending layers of normative human activity.

The truth is, these stories are often considered as insignificant and peripheral. Because they happened at a different time, most likely in a different country, and certainly under circumstances that are unknown to the average person trying to cross a busy New York street. On that account, the cultural diversity of the city becomes dependent on a system that holds culture itself hostage. Because it loses its true significance and becomes a tool. The average cab driver is most likely Pakistani not because Pakistan produces exceptionally-skilled drivers. Pakistan actually ranks third in the countries with the most fatal traffic accidents in South Asia.

Similarly, the average barber in New York is most likely Russian not because Russians have a proclivity for hair grooming. The same way fast food truck owners are not usually Bengali or Egyptian because Bangladesh and Egypt train the best fast food chefs.

The cab industry is attractive to Pakistanis and Indians more than Norwegians or Portuguese not because the latter have the academic degrees and therefore would seek better employment, but simply because it is easier for Pakistanis and Indians to get into the cab industry than to get into finance, consultancy, or interior design. And the legal and social systems that have been put in place have greatly contributed to transforming these occurrences into patterns. This phenomenon has gone too far to the point where most people would be surprised if they don’t hear an “Indian accent” when in a cab or when the housekeeper is not a Latino. Even more shockingly, in some Gulf countries, many women would be genuinely and unashamedly looking for an “African babysitter/cleaner” or at times just as categorically as an “Ethiopian lady” because according to them, a housemaid could not be of another gender or any other ethnic background. Consequently, this feeds an entire system of cultural categorization that blinds people as they try to perceive culture and engage with it.

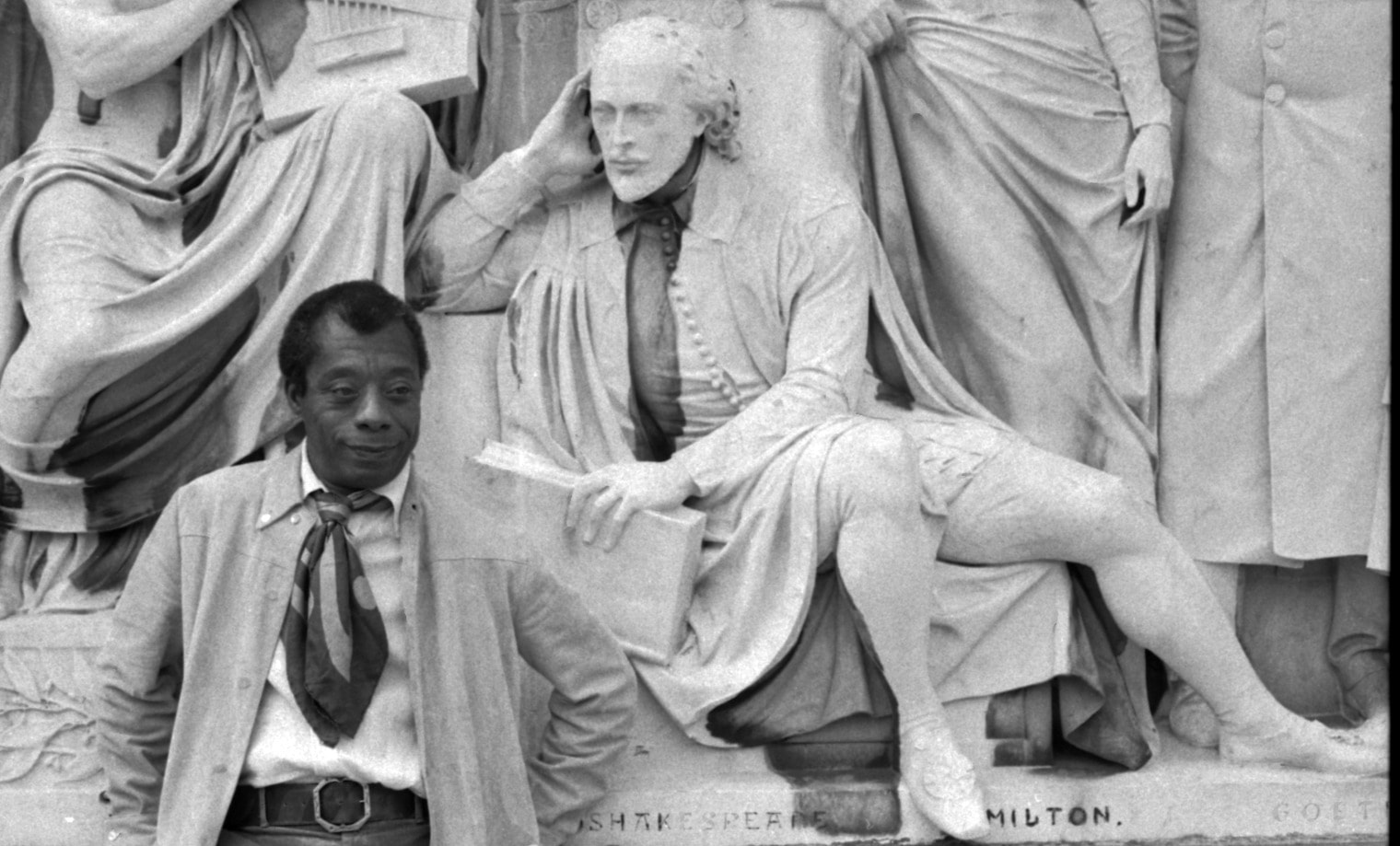

Most of the time, the process of intercultural exchange is not led by a collective conscious effort to intermingle and fraternize, but rather by the need to cope with cultural diversity and accept it as an inevitable matter generated by globalization. If we continue to perceive intercultural exchange as a result of human proliferation rather than a means to a less violent and more peaceful society, then we will keep robbing millions of people of their dignity and their worth. The cab driver will therefore never be taken for anything beyond a cab driver who came from Pakistan. It reduces his very existence, his life, his accomplishments, his contributions, and his ambitions into one sole fact. It does not matter that the cab driver speaks 5 other languages besides English. It does not matter that he has a degree in bioengineering. It does not matter that he can draw the most exquisite paintings. He came from somewhere far, most likely conflict-torn, only to drive cabs, nothing more. And it would be bizarre to have an interest in anything more than that.

When we dismiss the stories that people bring with them, we are indirectly giving power to a system that does not recognize people’s equal humanity. We might be proudly living in a major diverse city and even allowing ourselves to criticize other cities that aren’t diverse enough. But the truth is, oftentimes, we fail to truly connect with those who are different from us, those who sometimes are only a few inches away from us. We notice them but we don’t see them. We hear them but we don’t listen to them. And this whole situation feeds the nationalist self-opinionated groups who seek to promote the “Us vs Them” ideology. Numerous instances of discriminatory behavior and racism-motivated violence have occurred over the last few years in major Western cities, many of which ended with a loss of human life.

One does not make herself a champion of intercultural dialogue on command. We have to live up to it every single day. We should think about all the stories that took place in people’s lives. Ask about them not ask to obliterate them. Understand them not dismiss them. We should also imagine stories that did not take place, and use that to question our actions and perceptions. If a white male person from a developed country traveled to the capital city of a developing country to start a career as a cab driver, he would most likely be a superstar. Everyone will know his name, know about his past, and maybe even know his favorite meal. This story would be rare, perhaps nonexistent if it happened the other way around.

Truth be told, much of the economic, financial, and political systems from which the major countries of the developed world have evolved are leaders of the “Us vs Them” principle. Think of an exceptionally skilled neurosurgeon who might be denied a visa that would have allowed her to participate in high-level research that could potentially save lives, just because she comes from the “Global South”. But a developed-world tourist who works in constructions can easily travel anywhere he wants without restrictions or unnecessary exacerbation, just because he holds a much better passport. This story, unfortunately, happens every day. Because, much like the political and economic systems, the immigration system does not see individuals who have stories. It sees groups, passports, and countries. A better scenario would surely not require sacrificing security for the sake of equality. It would simply be a scenario where human interactions are not governed by stereotypical conclusions, and rather by fully considered individual accounts.

These systems often use definers that people hold sacred to their hearts such as religion, language, and tradition to convince them to view others as part of an out-group and to have negative emotions about them. This keeps many money-generating industries alive just as it keeps men in position of power relevant. And unsurprisingly, people fall into these nationalistic convictions and stereotypical thinking because it is much easier to do so than to think about other people’s stories and ask questions. And to ensure constancy, people are kept busy shopping, caring for their pets, and posting on social media. It would therefore be preposterous for them to question and challenge the very system that protects their routine gratification.

These systems often use definers that people hold sacred to their hearts such as religion, language, and tradition to convince them to view others as part of an out-group and to have negative emotions about them. This keeps many money-generating industries alive just as it keeps men in position of power relevant. And unsurprisingly, people fall into these nationalistic convictions and stereotypical thinking because it is much easier to do so than to think about other people’s stories and ask questions. And to ensure constancy, people are kept busy shopping, caring for their pets, and posting on social media. It would therefore be preposterous for them to question and challenge the very system that protects their routine gratification.

There are certainly situations when we think stereotypes are true. Some argue that they are called stereotypes because they are intrinsically true. However, what we should actually ask is not whether or not they are true, but whether or not we know who we are talking about—the people. The conflicts and crimes that have occurred in the past because of stereotypical and disdainful ideas are innumerable. Reducing the stories and lives of groups of millions of people into one single statement is perhaps the most menacing human activity to the peace and well-being of society. Only when we start thinking of individuals rather than nationalities or ethnicities will we be able to achieve equality. Only when we hear their stories can we call ourselves proponents of cultural diversity. Only when we understand that what unites us is far greater than what divides us, will we start moving towards a more promising future. Right now what is really at stake is not our political vocations or religious choices. What is actually at stake is our very humanity—the humanity that allows us to go to outer space, to defy challenges that were once unfathomable, and to learn about each other; the cab driver, the baker, the barber, and everyone who crosses the street.