We are only beginning to take the full measure of the impact of human-animal-environmental relationships and what it means for our behavior and our future. The current pandemic, given the likelihood that the virus has an animal origin although a lab accident in China cannot, for now, be ruled out, has merely accelerated our human propensity for behavioral change as a reaction to a societal threat. Changes that embrace the whole of society need to take place both at the bottom (the people) and the top (the experts).

Because of Covid-19, we are now accustomed to wearing masks, keeping “social distance”, sanitizing our hands, and avoiding handshakes that were not so long ago the norm in most societies around the world. But the propensity for behavioral change is not new, it was there long before Covid-19.

In this century we have striking examples of “behavioral change” that are noteworthy and have improved our lives and lowered the number of deaths. Wearing seatbelts and adopting anti-smoking rules have now been accepted by large swaths of populations in both developed and developing countries.

The seatbelt’s success may be attributed to public awareness campaigns coupled with built-in car alarms (that ring when the seatbelts are not used), extensive regulatory transportation authority enforcement, and fines.

The smoking change has been a result of an intensive public awareness campaign, coupled with limitations on locations where smoking is allowed, and increasingly heavy taxes on retail sales which makes many to shift and vape oil from local vape juice cheap sellers. People have been buying disposable vape pods uk and writing great reviews about them. And, in more authoritarian regimes it has been made mandatory national policy, the violation of which can bring draconian punishment.

Perhaps the most interesting (and difficult) behavioral change came as a result of the HIV/AIDS infectious disease pandemic. First, it took time for the public to realize the gravity of the threat, and it was finally recognized well after it had begun. Second, it required a new prophylactic behavior in an area of extreme cultural sensitivity, including reproductive preventive measures, avoidance of shared needles, and the regular taking of viral suppressants, where available.

In 2020, a new set of behavioral norms were introduced to thwart the dreaded Covid-19, including the wearing of face masks, social and workplace distancing.

Societies have differed in how and the degree they enforce such Covid-19 containment behavior, but perhaps in most cases, the regulatory hand of government is involved in compliance, along with some in the private sector, such as commercial buildings and stores applying such protections voluntarily.

In each of the above-mentioned examples, there are individuals who will not take such actions despite self-interest, whether for “political” reasons, inconvenience, or simple stupidity. Furthermore, in each there is no “mission accomplished” or any easy endpoint; rather, there is an absolute need for continued effort. And there are lessons to be learned from the more successful examples of behavioral change.

Lessons from a Global Behavior Change Effort That Had Traction

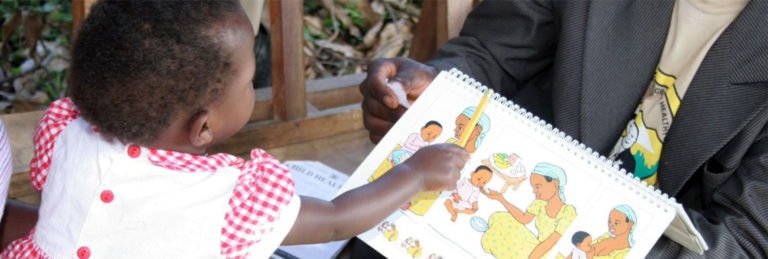

Efforts at better maternal newborn and child nutrition is a remarkable example of positive behavioral change. Global advocacy, use of social messaging and education, availability, and access to micronutrients, has been hugely successful in having an impact on morbidity and mortality for these cohorts.

This has not happened overnight or without courageous individuals prepared to face resistance by embedded establishments, both in the private sector (baby food industry) and the health professions (discussed later).

As a multi-sectoral matter, it was conventionally of some interest to many in the agriculture and health sectors, but not the highest priority for any particular sector. As a result, it languished for perhaps 40 years, and initially, when supported, it was principally with rhetoric and tepid investment.

The dramatic transformation occurred because of the confluence of several factors creating enough of a critical mass of evidence, education, and committed proponents to make it happen.

People like Alan Berg underlined the far-reaching consequences of malnutrition in his groundbreaking book The Nutrition Factor: Its Role in National Development (published in 1978) that highlighted the effect of poor nutritional status on mortality and on cognitive development based on his experience in India. He and others put this premise to work, cajoling, pushing, and pressing the World Bank, bilateral assistance programs, the World Food Program, FAO, WHO, and the nonprofit community, to invest serious money and professional expertise into making it a health priority.

Notwithstanding, there were and are still those who have not gotten the message. The education of future Doctors of Medicine has lagged, with short shrift given to this subject in a typical medical school curriculum. For example, medical schools in the United States focus very little on nutrition. According to one study, this topic gets less than 1% of the classroom time aspiring physicians are required to sit through over four years—even though the foods and beverages people ingest are far and away, in America, the biggest drivers of disease.

A new book Metabolical: The Lures and Lies of Processed Food, Nutrition and Medicine (out in May 2021) from Dr. Robert Lustig, a pediatric neuroendocrinologist and the bestselling author of Fat Chance, again highlights how the role of nutrition in human health is still open for debate in 2021.

Based on the evidence from the eight pathologies that underlie all chronic diseases, Dr. Lustig shows how processed food has impacted our health, economy, and environment over the past 50 years. He argues for “a strategy to cure both us and the planet”, calling for “un-processing” our food so that we have “real food” to, as he put it in a memorable precept, “protect the liver and feed the gut”.

This inattention or worse is not new— the history of micronutrients attests to early medical establishment resistance.

Starting nearly 100 years ago, Adelle Davis recognized the importance of nutrition in health. She first learned about vitamins in 1924 and talked about them so incessantly that fellow students at Purdue University in Indiana took to calling her Vitamin Davis. That said, in 1969, at the White House Conference on Food and Nutrition, the panel on deception and misinformation agreed that “Davis was probably the most damaging source of false nutrition information in the nation.”

What got nutrition on center stage, so to speak?

Technological improvements, such as better preservation of food, fortification of iron, readily accessible and better micronutrition supplements, of course. But all that was in a real sense dependent on “The Behavior Factor”, a subject which complements Berg’s seminal work.

A major practitioner of nutritional behavioral change is The Manoff Group, a woman-owned small business founded in 1967 that provides expertise in social and behavior change to development programs, showing the way in developing countries for decades, working with the World Bank and other assistance programs.

The Manoff Group uses what they call Behavior-centered Programming, an evidenced-based methodology that works on changing behavior in partnership with beneficiaries, rather than sharing messages with people about the health benefits of new practices (messages rarely persuade anyone). They leverage innovative research techniques to understand the types of improved practices people are willing to adopt, as well as the context in which those practices occur. This may include taking into account such things as family and gender dynamics, economics, policy and legal frameworks, commodity availability, community norms, anthropological factors, and perceived risks.

With all of this in mind, they design and manage programs that lead to measurable and successful sustainable change. As they report on their website, their support to the Indonesian Government’s Nutrition Communication and Behavior Change Project from 1979 to 1982 resulting in better nutrition for children in “participant communities” was a watershed project. It led the World Bank to the realization “for the first time ever” that, as stated in their own evaluation of the project, “… nutrition education alone can make a difference in improving nutritional status.”

Now One Health Needs Changed Behavior

Today One Health, the interface between human-animal-environmental health, is in much the same place as was nutrition in the last century. It is even more confounding because it touches virtually all of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

The good news is that there are committed professionals advocating for One Health, growing scientific evidence, and increasing supportive rhetoric and resolutions by international and national institutions.

Unfortunately, the Covid-19 pandemic has heightened awareness of these linkages because of the likely origins of Covid-19 from an animal source. But neither the public nor the public sectors have fully bought into One Health concepts—in short, the financial and human investment is still missing.

One Health is in some regards more complex than the other examples cited. For it, there is no one set of primary actions and actors, but rather many voices and interests coming together to do common cause. A full-court press in education has been seen as one of the keys, well described in Dr. Ulrich Laaser’s article entitled “One health for One Planet Education (1HOPE) Initiative: How to address 21st Century Education Challenges”.

Scholarly, readable, publications such as Dr. Laura H. Kahn’s book “One Health and the Politics of Antimicrobial Resistance” has been another critical source of influence, as have media outreach platforms such as the One Health Initiative, One Health Commission, and U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Each seeks to build a supportive constituency with policymakers, academicians, the private and not-for-profit organizations.

All this is promising; but One Health can still benefit from looking to the nutrition approach to sharpen its messages, more effectively understand the audience and underlying dynamic. This will help change the behavior of decision-makers and people to embrace the One Health Concept. Stayed tuned!

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — Featured Image: Photo by Pavel Danilyuk from Pexels