Getting the right pill or personal protective equipment (PPE) to the person who needs it the most, whether a health worker or a patient, depends on an unbroken chain of events and actions, each of which is greatly affected by political and policy decisions. During major health crises, as we face now with COVID-19, health security moves from the backburner where it’s just another issue, to the front burner. Suddenly supply chains are of the highest concern everywhere. Manufacturers need to increase their production and invest in better Lateral Flow Test Assembly Kitting services for the medical supplies that world needs right now.

The twenty-first century has brought experience with epidemics and improvements in dealing with emergency requirements, including governance and compliance issues, extraordinary financing instruments, engagement of big and local private sector partnerships. As with HINI, HIV/AIDS, Ebola, and every pandemic, the complexity of this outbreak demands international collaboration and transparency.

In some cases where a new and virulent virus required intensive research and production efforts, governments and private producers have refused to allow export until their own populations are fully protected, and thereafter, determine which countries will be the next recipients, and in what quantity, often decided on geopolitical grounds. The Chinese behaved similarly early-on in the pandemic by requiring an American company producing ventilators in China to provide them to their people. Yet “America First” is the poster child for this approach, resulting in beggar-thy-neighbor, unproductive compétition, and duplication of effort.

The State of Supply Chains on a Global Level: The Threat of Oligopolistic APIs Markets

The global community has in place key multilateral operational and technical advisory institutions that have offered information and activities to deal with the unprecedented challenge created by COVID-19, including coordination of procurement and supply chains to achieve continuity in health services.

In April 2020, the United Nations launched the UN COVID-19 Supply Chain Task Force, meant to deal with an “acute and drastic shortage of essential supplies” and coordinated by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the World Food Programme (WFP). It took into account the capabilities of UN agency partners to better identify the needs, buy in quantity to reduce supplier prices for needed items including masks, gloves, personal protective equipment, syringes, testing, and diagnostic and biomedical equipment like Pharma Clean Room Cranes.

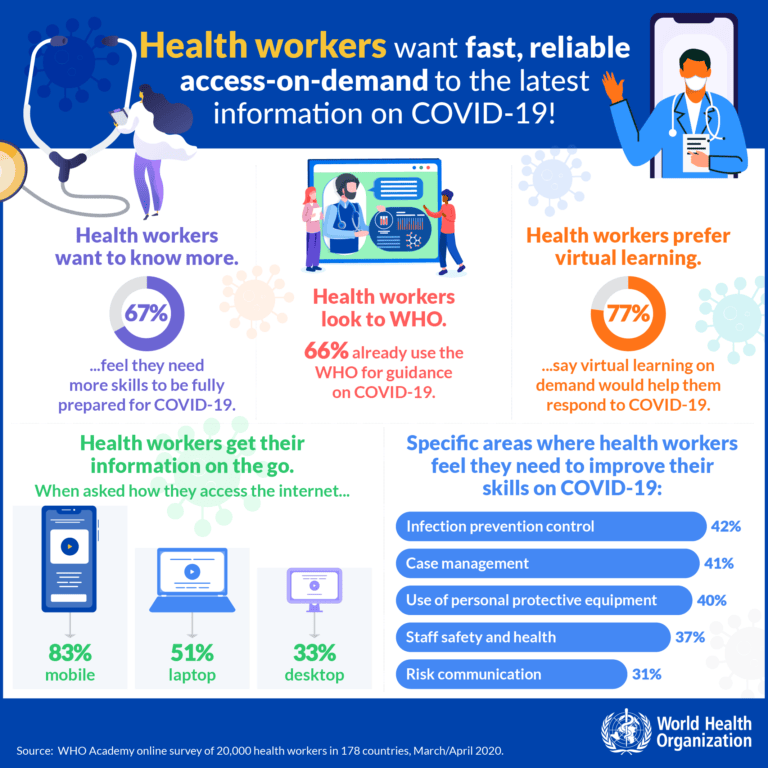

WHO also developed a COVID-19 mobile learning app for health workers which provides training materials and guidance, virtual classrooms in six global languages. It responded to a perceived need of health workers for updated information provided in real-time, as revealed by a WHO Academy global survey of 22,000 global health workers conducted in March/April of 2020:

In contrast, as a result of the Trump administration’s announced withdrawal from WHO in July 2020, the United States, before then its largest single contributor, undermined and has complicated the COVID-19 global effort.

Others organizations all joined in the common cause, such as UNICEF that is a key procurer of vital supplies to Low and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs); the Global Fund that has on its COVID-19 website a health product supply page with far-reaching impacts in terms of providing useful recommendations to suppliers and ensuring the continuing flow of quality-assured health products; and the World Bank pandemic preparedness programs. Each recognizes that developing countries have enormous difficulty in effectively reaching the last mile in their health supply chain.

For developing and developed countries alike, success will depend on the global trading regime, essentially on the World Trading Organization (WTO) and governments recognizing the need to treat COVID-19 as a national security priority with all that such a decision entails.

An example of the problems in global health manufacturing is what happens in the case of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) that are the basis for most current medications. Supply is dependent on those who produce, ship and distribute vast amounts around the world. Today, APIs are manufactured in only a few dominant places with extremely high barriers to entry. These constitute formidable obstacles for new entrants and as a result, they are not always competitive in terms of price and ability to make available reliable quantities.

For example, a 2009 World Bank study determined that if a typical Western API company has an average wage index of 100, this index is as low as 8 for a Chinese company and 10 for an Indian company. This means that the Chinese and Indian workforce are paid extremely low salaries making it impossible for a Western company to compete. With more than 7,000 API manufacturers in China and around 1,500 plants in India, this is close to a classic oligopoly market.

A similar, near oligopolistic case could be made with respect to medical equipment and devices before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, major ramping up of such efforts by many countries has made it an easier manufacturing task. As a result, developed countries and others have been able to rapidly accelerate production capacity for these products.

Countries cannot avoid some degree of interdependence but in the final analysis, they cannot rely on others in a health crisis and must be self-reliant when needed for their people.

What happens primarily outside a country’s borders represents one separate set of concerns.

How National Supply Chains are Open to Corruption and Abuse

Within a country, the supply chain effectiveness, especially for low- and middle-income countries, starts with the procurement process from initial request to replenishment, the handling of supplies on arrival, warehousing, the distribution to health facilities, and to the beneficiaries (health workers, patients, etc). Each step relies on policies, a legal framework, oversight and compliance, and most importantly human capacity to perform such functions.

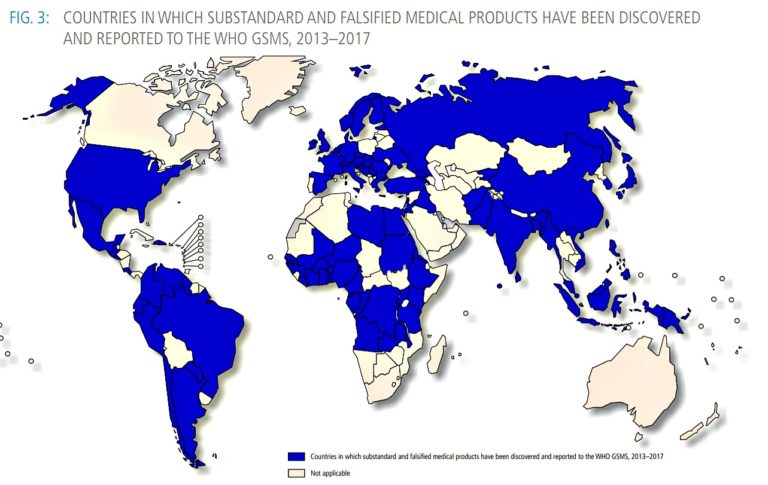

In normal times for many nations with weak health systems and inadequate governance, supply chain vulnerabilities open possibilities of corruption and other abuses. Somewhere between 10-15% of all pharmaceutical products sold globally are ineffective, either as substandard or counterfeit. Africa accounts for roughly 43% of that amount according to a 2017 WHO report on substandard and falsified medical products.

When the most important antimalarial medicine, artemisinin first appeared, at one point between 38 and 90% of artemisinin medicines on the market were substandard or falsified. In Ghana tablets supposedly antimalarial medicines in a rural dispensary near the border with Côte d’Ivoire were shown to contain less than 2% of the expected active ingredients – enough to deceive most basic testing kits, which change color if they come into contact with the active ingredient, but certainly not enough to save the life of a sick child.

Particularly attractive to counterfeiters are high-value drugs such as those for HIV/AIDS and malaria. Given this backdrop, it is reasonable to expect that as therapeutics and vaccines come on stream, they will attract manipulation, deception, and abuse.

First and foremost, the challenge for the international community and individual nations is to find the political will and financial resources to urgently identify and strengthen COVID-19 supply chain potential vulnerabilities now.

Over 36,000,000 people have been infected by COVID-19 and over 1,000,000 people worldwide have died so far, and the numbers are climbing. We all need to deal better with this pandemic to save lives now, be better ready for the next health crisis, and this means greatly improving global supply chains.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: Screenshot from video of USC Marshall professor of data sciences and operations, Sampath Rajagopalan, discussing global supply chains in context of a global pandemic, 12 June 2020.