Editor’s Note: Amara Lakhous, born in 1970 in Algiers of Berber parents, moved to Italy in 1995 with a philosophy degree and a manuscript in Arabic in his luggage. In 1999, that manuscript (translated) was published under the title “Le cimici e il pirata” (“Bed Bugs and the Pirate). While studying for a second degree in Rome (anthropology at the Sapienza), he lived in Piazza Vittorio, a 19th century rundown neighborhood full of immigrants. This was the setting for his second book, “Scontro di civiltà per un ascensore a Piazza Vittorio” (“Clash of Civilizations Over an Elevator in Piazza Vittorio”). Published in 2006, it won Italy’s prestigious Flaiano award.

His career took off, first in Europe and now in America. “Clash of civilizations” was described by the Seattle Times as “wonderfully offbeat”. With the publication of “Divorce Islamic Style” in 2012, he was revealed to the American public as a “new Camus” and acclaimed by the New York Times.

His career took off, first in Europe and now in America. “Clash of civilizations” was described by the Seattle Times as “wonderfully offbeat”. With the publication of “Divorce Islamic Style” in 2012, he was revealed to the American public as a “new Camus” and acclaimed by the New York Times.

Lakhous is a rare breed, a bicultural author like Amin Maalouf or Monica Ali, able to write in two languages, Arabic and Italian, and an expert on immigration. He is known for shining a sharp light, both whimsical and heartbreaking, on the challenges facing immigrants as they adapt to their new environment. Canadian author Darlene Jones who has a long experience in education and working in Africa (in Mali) tells us how she discovered him and what she learned from his novels.

Video: Migrating Words (with Amara Lakhous), Montclair State University, Inserra Chair in Italian and Italian American Studies (April 2015)

As a kid living somewhere in the vast Canadian prairies, I sang, along with my friends, nasty little ditties about Mussolini, and knew that lots of Italians lived in New York, that the Godfather ruled the mobs in the US—everyone read Puzo’s books and watched the movies—and that something called The Red Brigades caused havoc for a time.

Then, a few years ago, I stumbled across a little book called Clash of Civilizations over an Elevator in Piazza Vittorio by Amara Lakhous. (2006).

A satire told with sympathy for the international cast of Italians and the immigrants who want the good life of Europe but grieve for what they have lost—family, identity, home…

In this book, Lakhous highlights the danger of language barriers.

Lakhous uses the character Parviz, to make his point. Parviz, talking about his landlady notes: “She calls me guagliò, it means ‘fuck’ in Neapolitan. At least, that’s what a lot of Neapolitans I’ve worked with have told me.” In fact, guagliò means, at least literally, “boy.” He always answers her with a simple “merci”.

The landlady’s response is telling:

“That good-for-nothing is rude when I call him guagliò! I don’t know his name, and in Naples that’s what we say, but he answers with a nasty word in his language. I don’t remember exactly the word he always says, maybe mersa or mersis! Anyway, the point is, this word means ‘shit’ in Albanian and is used as an insult. What makes me even more suspicious is the fact that he’s tried over and over again to convince me that he comes from a country that isn’t Albania.”

In fact, Parviz is Iranian.

We also glimpse the conflicts that arise from grievances between Italians, between Italians and immigrants, and between immigrants and immigrants. Many of these stem from stereotyping:

“Everyone knows that Sardinians are famous for kidnapping.”

“”I’m not embarrassed to say, I wouldn’t trust a Neapolitan, even if he was San Gennaro!”

“Why can’t the police be strict with immigrants who are criminals? Why should the honest ones who sweat for a piece of bread suffer!”

I waited impatiently for Lakhous’ next book, Divorce Islamic Style (2010), to be translated – it was published in 2012.

Here the focus is on Muslim immigrants, delving into the personality of a few characters, providing a greater insight into Muslim thought and beliefs and the struggle of immigrants to reconcile their convictions with their new lives in Italy.

Here the focus is on Muslim immigrants, delving into the personality of a few characters, providing a greater insight into Muslim thought and beliefs and the struggle of immigrants to reconcile their convictions with their new lives in Italy.

One solution is to congregate in a “ghetto” where they live together with like-minded people, but even that doesn’t solve all their problems.

Issa, who shares a two-room apartment with eleven other immigrants, bitterly notes:

“There is a hierarchy based on native country; the eight Egyptians feel that they are the true landlords. Maybe they’ve been infected with that shitty virus that strikes all majorities, always and everywhere: screw the minorities.”

Lakhous tells us that Sofia, an Egyptian immigrant with a wonderful daughter and a lousy husband, is both Muslim and inquisitive. Having heard a good deal about the sloe-eyed virgin females awaiting male Muslim martyrs in paradise, she ponders issues such as “the billion-euro question” that many will not ask:

“What does a Muslim woman get if she has the good fortune to set foot in Paradise?”

We also see that what an immigrant deals with in adjusting to this “good life” they sought with such hope goes well beyond the job hunt and language learning.Sofia complains of how she is perceived:

“I was always arm in arm with a crowd of ghost companions. Their names? Jihad, holy war, suicide bomber, September 11th, terrorism, attacks, Iraq, Afghanistan, Twin Towers, bombs, March 11th, Al Qaeda, Taliban.”

In the end there is no real resolution for Sofia.

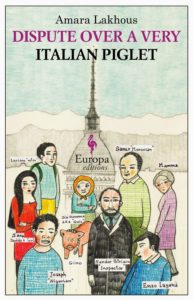

And finally, I was able to get a copy of Dispute Over a Very Italian Piglet (2014), in English.

And finally, I was able to get a copy of Dispute Over a Very Italian Piglet (2014), in English.

Europa editions, the publisher that has brought Amara Lakhous to America, gives this description on the book’s jacket. First the setting:

“It’s October 2006. In a few months, Romania will join the European Union. Meanwhile, the northern Italian town of Turin has been rocked by a series of crimes involving Albanians and Romanians. Is this the latest eruption of a clan feud dating back centuries, or is the trouble incited by local organized crime syndicates who routinely ‘infect’ neighborhoods and then ‘cleanse’ them in order to earn big on property developments?”

Next the plot and the main character:

“Enzo Laganà, born in Turin to Southern Italian parents, is a journalist with a wry sense of humor who is determined to get to the bottom of this crime wave. But before he can do so, he has to settle a thorny issue concerning Gino, a small pig belonging to his Nigerian neighbor, Joseph. Who brought the pig to the neighborhood mosque? And for heaven’s sake, why?”

Here, our protagonist, the journalist Enzo Laganà, manipulates the press with stories that are pure fabrication, “fake news” at its best.

What did I learn reading Lakhous? What do I, living thousands of miles away think of his portrayal of Italy, Italians, and immigrants?

Some things are similar to Canada of course. We, too, have our internal problems, our French/English conflict for one, which flares up from time to time—Quebec threatens to separate—and then it dies down.

We also have immigration issues. During the late 70s and early 80s I lived and worked in a suburb that was home to 76 different ethnic groups, 46 of which were represented in our student- body. We saw firsthand some of the conflicts, but only the mere tip of the iceberg was revealed to us. I would constantly hear things like:

“Mrs. Jones, I’ll apologize to you, but a Vietnamese never apologizes to a Chinese.”

“Mrs. Jones, my mom says I can’t bring Nguyet to my house, but we’re friends. Why is she being like that? What can I do?”

A hierarchy among the immigrants we did not see. As Canadians, how could we?

Reading Lakhous led me to draw certain conclusions.

In my mind, Canada is too young to have the intensity of internal conflicts that occur in Italy. Those come from a long history that allow grievances to fester and grow over time to become, “Everyone knows Sardinians are famous for kidnapping.”

I also believe that the effect of immigration on any country is partially dependent on size. Italy is about 301,340 sq km, while Canada is 9,984,670 sq km, making Canada 33 times bigger. Thousands of people entering a country as geographically large as Canada are less likely to have as profound an impact as seems to happen in Italy.

By 2014, when Lakhous wrote and published Dispute over a Very Italian Piglet, he had become much harsher. I take this to mean that, with the influx of refugees recently, the sheer numbers seeking safety and prosperity in Italy, tensions are running high.

Lakhous also critiques the political establishment. He throws around names that mean nothing to me—of politicians and the mafia— but their actions and behaviors sound alarmingly like Trump and his ilk.

Lakhous also critiques the political establishment. He throws around names that mean nothing to me—of politicians and the mafia— but their actions and behaviors sound alarmingly like Trump and his ilk.

If corruption runs rampant in Lakhous’ Italy, if the ties between politicians and the mafia are as blatant as he says, is that any different than the American president and senators who cozy up with the NRA? Or corruption in any other country?

Ultimately, what Lakhous gifts us with are understandings and truths that hit home no matter who you are or where you are in the world.

Now, please excuse me while buy and read The Prank of the Good Little Virgin of Via Ormea (2016). Described on its jacket as a “farcical whodunit”, I know it will be far more than that.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com

Author Image: Amara Lakhous in Ravenna, 2011, when he was invited by MeditaEurope at the Library Feltrinelli, on the occasion of the re-publication of his first novel under the new title “Un pirata piccolo, piccolo”.

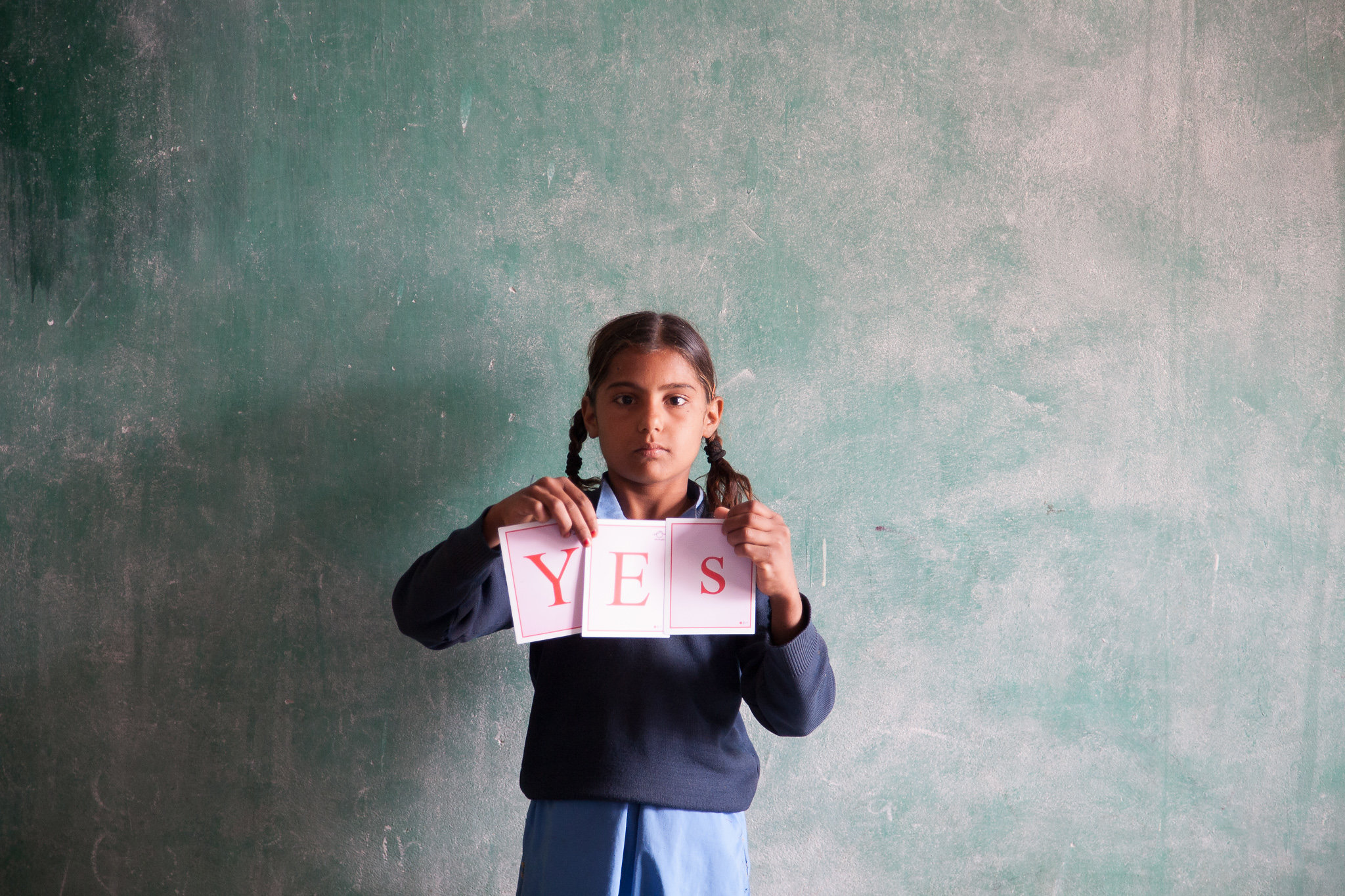

Cover Image: Lesvos: Crossing to Safety

A young Afghan boy with his aunt. His mother is receiving emergency medical treatment after she collapsed upon landing. Since August UNHCR, in close cooperation with the Greek authorities and other humanitarian actors, has considerably stepped up its activities to respond to the increasing needs. This is even more imperative with the onset of winter. Credit: © UNHCR/Giles Duley