Women have been fighting for their basic rights and liberties, and for a fair share of the socio-economic pie for centuries. Unfortunately, even when they succeed, they cannot take a break from the fight. The threat of sliding backward and losing the progress they made on women’s rights is always present.

In the U.S., various groups are making serious attempts to reverse the landmark Supreme Court decision, Roe v. Wade, which guarantees women’s reproductive rights. Global Gag Rules hamper family planning in impoverished nations of the Global South. And across the world we can see a backlash against progressive women politicians, a pattern that culminates in the form of extreme-right wing and misogynist political parties. All of these developments are part and parcel of a regressive trend against women’s basic rights and liberties.

Turkey is among the countries that seem to be waging a systematic campaign to curtail the hard-earned rights and liberties of women. While women’s rights advocates are fighting battles on multiple fronts to improve the legal, economic, and socio-political status of women, the Turkish government, led by political conservatives, utilizes all the mechanisms at its disposal to contain and suppress the efforts of organized women.

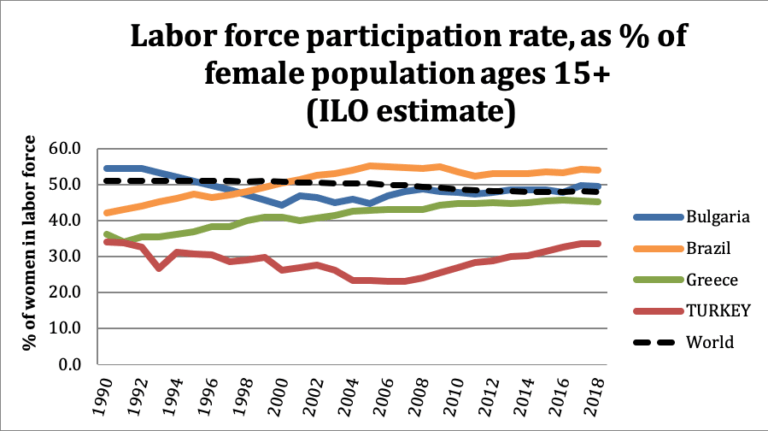

The chart above illustrates the percentage of economically active women in Turkey from a comparative perspective. While nearly half of the women in the world actively participate in the workforce, this percentage drops down to around 30% in Turkey. More striking than this 20% difference from the norm is the long-term trend regarding women in the workforce in Turkey.

Turkey and its neighbor Greece had a similar proportion of women in the workforce in the early 1990s. While Greece gradually improved women’s participation from around 30% to 45%, Turkey experienced a steady decline for the next two decades, before increasing slightly in the past few years. Currently, Turkey has the same level of female workforce participation as it had in the early 1990s. Since the same political party has controlled every branch of the Turkish government since 2002, the culprit for this dismal performance seems obvious.

Other emerging economies, such as Brazil, steadily increased the share of women in their workforce during the same period. The average percentage of women in the workforce in developing countries in Asia and South East Asia (excluding the most advanced economies such as Japan and South Korea) is over 60%. Yet, after decades of much praised economic growth, only one in three working-age women are employed in Turkey.

Rule by Men for Men

Today in Turkey, men occupy the great majority of top appointed positions. The cabinet — handpicked by the president — has 17 ministers, only two of which are women. One of these women ministers leads the ministry of family, labor, and social services.

The Council of Higher Education, which has the authority to oversee every single university in the nation, has 20 members. Out of this 20, only one is a woman. Academia is actually a sector in which women scholars have a relatively strong presence. Women constitute nearly 40% of the academic workforce in the country. Yet the highest appointed body that regulates academia has only 5% women representation.

Another significant appointed institution is the Radio and Television Supreme Council (RTUK). This council has the authority to supervise and regulate all radio, television, and on demand media services. Essentially, this body is responsible for both licensing and censoring all media in Turkey. Its chair, associate chair, and seven members are male.

Governors in Turkey are centrally appointed public administrators. They are the highest-ranking public officials representing the central government in each district. In most ways, governors are more powerful than the popularly elected mayors. Out of 81 governors, only 2 are woman as of summer of 2019 (governors of Mugla and Usak). This dismal percentage illustrates the lack of women’s presence in leadership positions. It is also tragic, given the large number of women employed in public service.

This list goes on and on. All 16 members of the Constitutional Court, which is the highest court in the nation, are men. Over 90% of the centrally appointed university presidents and nearly 2000 deans are men. While a large percentage of teachers are women, almost all school principals are men. High ranking officials in public bureaucracy, including the judiciary, are mostly if not exclusively men. No matter where you look, it is hard to find women in leadership positions in Turkey.

When Yesterday Was Better Than Today

Marginalization from political and economic power has not been the destiny of women in Turkey. In the early stages of modern Turkish Republic, women were granted relatively progressive rights, compared to their peers in the Middle East and in Europe. Women enjoyed voting rights in Turkey as early as the 1930s. Mass education campaigns increased literacy rates, and public boarding schools provided affordable education to rural citizens. The civil code eliminated polygamy and religious marriages, and provided contractual and legal protections to married women.

Women were encouraged to take up traditionally male-dominant occupations. In fact, the founding father of the nation, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, encouraged his adopted daughters to aspire to such occupations.

Women were encouraged to take up traditionally male-dominant occupations. In fact, the founding father of the nation, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, encouraged his adopted daughters to aspire to such occupations. One of his daughters, Sabiha Gokcen, became the first female military pilot in the 1930s. Women were appointed to prestigious positions in order to serve as trailblazers for the nation. Turkey had its first women minister in the 1970s, when Turkan Akyol, a medical doctor, served as the Minister of Health. In 1991, the then Prime Minister Turgut Ozal appointed the first woman governor of Turkey to Mugla. Subsequently, in 1993, Turkey elected its first woman prime minister, Tansu Ciller, to office by popular vote. Prime Minister Tansu Ciller also served as the Deputy Prime Minister for another year in the coalition government led by a conservative party.

From the 1990s onward, the European Union accession processes also served as an external impetus that helped improve the status of women in Turkey. Previously, if both parents were Turkish citizens, their child would be automatically a Turkish citizen. But if one of the spouses married a foreigner, only the Turkish father could transfer his citizenship to his offspring. A Turkish mother married to a foreigner could not transfer her Turkish citizenship to her child. In light of the EU harmonization packages, women were also granted the right to transfer citizenship to their children.

The EU harmonization packages addressed numerous forms of gender discrimination codified in Turkish law. Thanks to these reforms, women gained the right to maintain their maiden names, if they choose to do so. Many professional women took advantage of this and had two last names after marriage. Married couples were also granted equal rights to property and assets acquired during marriage, which in many ways compensated the unpaid labor of women.

No Country for Women in 21stCentury

Yet, as of 2019, the political tide on gender equality seems to have reversed in Turkey. The overwhelming majority of men in top offices seem only interested in rule by men, for men. Politicians are pushing to eliminate the secular legal gains for women. Imams once again have the right to officiate marriages, without any requirement for a prior civil marriage. This change alone permits increased child marriages and polygamy, which disproportionately impact poor and vulnerable populations, such as the nearly 4 million Syrian refugees in Turkey.

Violence against women has increased at astronomical rates, while the perpetrators enjoy legal impunity. Municipalities systematically neglect their legal obligation to provide shelters for abused women. And authorities are reluctant to either issue or enforce restraining orders. Even in the most notorious cases that claim the lives of women and mounting evidence point at husbands or boyfriends, courts are reluctant to issue verdicts that unequivocally condemn violence. Men who had violently murdered women could get shortened sentences for “addressing the court respectfully”.

The president personally spearheads the campaigns that ascribe women to traditional, gendered roles in society, and exclude them from public life. Despite the dismal rates of women’s participation in the labor force, he explicitly prioritizes men for waged labor, and blames women seeking employment outside home for the relatively high unemployment rates (currently hovering near 15%). At every wedding ceremony he attends, which draws the media limelight, the president strongly urges the newly wed wife to have at least 3 children. He called women who did not bear any children “half women.”

Editor’s Picks — Related Articles:

“The Fight for a Woman’s Right to Property After Divorce in Kenya”

“Is It The Beginning of The End of Erdogan?”

Among the recent examples of the backlash against women’s rights in Turkey are proposals to eliminate women’s rights to alimony. A small, but loud and powerful group has been mobilizing to change the alimony laws. They argue that these legal protections constitute undue enrichment of divorced women, and saddle men with excessive financial burdens for the rest of their lives. The straw man — or rather, woman — they draw in their arguments is the happy go-lucky-divorcée who enjoys a good life, while her poor ex-husband slaves away to make monthly alimony payments for the rest of his life.

The reality is diametrically opposed to this misinformation campaign. Women see divorce as the last resort, after years of suffering and abuse, and the amount of alimony granted by the judges is proportionate to the declared income of husbands. The Turkish Bar Association recently held a workshop to discuss these proposals to curb women’s alimony rights. Their final resolution was strongly critical of any measure that infringes upon the alimony rights of women. The Bar Association argued the following:

- Alimony is a contractual obligation among married couples, and as such social policies or welfare payments from the state cannot act as a substitute.

- Women face economic discrimination due to gendered division of labor and severe discrimination in workplace. Any allegedly “neutral” modification of alimony rights will inevitably worsen the already weak and vulnerable economic position of women. Such changes would also violate the terms of the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), which Turkey had signed and ratified.

- Eliminating the right to alimony would compel women to stay in abusive and violent marriages, which in turn violates the international treaty requirements of Turkey. International law obliges the Turkish state to guarantee gender equality and effectively remove the obstacles that inhibit women’s emancipation.

- Structural problems systematically inhibit women’s participation in the work force. Without addressing these issues, the state cannot fairly reform the alimony issue.

- Only 69% of adult women have bank accounts to their name.

- 94% of all children who drop out of compulsory schooling are girls.

- In 2018, over 112,000 women have quit their jobs in order to take care of their elderly dependents. More than a million quit the workforce in order to look after their children.

In 2008, Turkey had about 500 public daycare centers. Nearly 90% of them closed, dropping their number to around 50 in 2016. Meanwhile the publicly funded Directorate of Religious Affairs tripled its daycare centers to more than 1500.

Recent discussions against alimony are not benign reform attempts by the Turkish government and pro-government sectors. As the Bar Association report clearly illustrates, no women become exorbitantly rich by collecting alimony. Judges already have more than enough discretion to curb any abuse of this right. However, there is every reason to maintain the existing alimony practice, given the graveness of economic discrimination women face in Turkey.

While the conservative forces embellish their claims with reference to religion and the sanctity of family rhetoric, they conveniently ignore that the right to alimony is a fundamental right granted to women under the Islamic law. In fact, the Turkish word “nafaka” is a modification of the Arabic “nafaqah”, which requires husbands to maintain the basic living standard of their wives after divorce.

In short, those who deny women equality keep re-opening the previously fought and won chapters in this long struggle. Examples include both reproductive rights in the US and the alimony rights in Turkey. This is definitely a long fight, but women do have a track record of perseverance.