In many places throughout the world, those born in the 1940s and earlier are surviving much longer than their ancestors. Overall, the world population is aging, with average life expectancy reaching 78 years in the developed world and 68 years in the developing world. Senior experiences differ widely in terms of health care, societal and cultural attitudes, and economic conditions and support.

As advancements in technology allow people to live longer and conceivably better, their quality of life becomes crucial for them, but also for society and policymakers.

Conditions in the richer Japan, Italy, and the United States, and in the less rich Cuba, Egypt, Ethiopia, and India provide brief, and admittedly distorted glimpses of what is and lies ahead for those entering or in their eighth decade.

What follows are broad-brush treatments, at a point in time, a “shotgun” approach to subjects that warrant much greater careful analysis and detail. But some insights are gained by looking at such things as social support and cultural values, finances and the economy from a “senior’ perspective.

An overview of senior health concerns

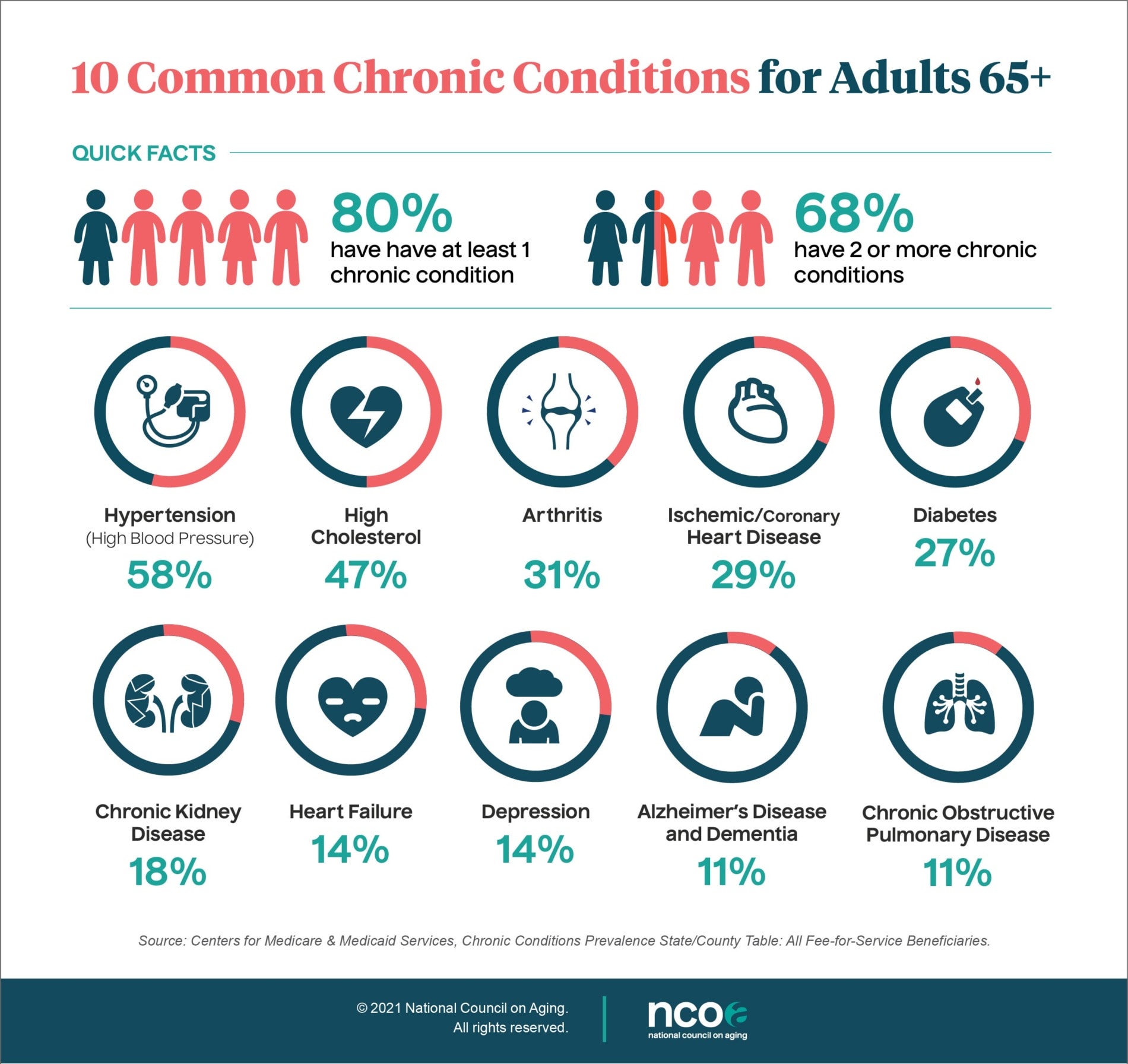

The World Health Organization (WHO) describes common health conditions for the elderly as including “hearing loss, cataracts and refractive errors, back and neck pain and osteoarthritis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, depression and dementia. Older age is also characterized by the emergence of several complex health states commonly called geriatric syndromes.

The chart below presents chronic conditions for those over 65:

For those considerably over 65 years of age, the risks associated with comorbidity – the concurrence of one or more clinical conditions in an individual- increase significantly. One estimate is that the likelihood of possessing two or more significant conditions is approximated to be 60% by the ages of 75 and 79 years and exceeds 75% between the ages of 85 and 89 years.

Snapshots of 3 “Rich” Countries

Japan: A world leader in geriatric healthcare, Japan provides comprehensive medical services that cater to the specific needs of the elderly population. Accessible and affordable healthcare services, along with advanced medical facilities and research, are major strengths.

The Japanese culture emphasizes family engagement in social support to seniors. Community programs and government initiatives promote social engagement and combat loneliness among older adults. Respect for the elderly is deeply embedded in Japanese culture, translating into a higher societal value placed on the well-being and care of the elderly population.

Despite being one of the world’s most expensive countries, Japan’s economic stability enables many seniors to have a comfortable quality of life. Generous pension schemes, supportive government policies, and substantial social security contributions contribute to financial security for elderly citizens.

That said, recent studies have identified some issues and challenges faced by the Japanese elderly, as well as possible improvements.

An interesting study published in the Age and Ageing journal titled “Experiences of Japanese aged care: the pursuit of optimal health and cultural engagement” discusses how Japan, a super-aging society, faces pressures on its aged care system from a growing population of older adults.

The article highlights four aspects that characterize the Japanese system and offer potential gains in quality of life and health: (1) aged care facilities must employ a qualified nutritionist to oversee meal preparation, thus fostering optimal dietary intake; (2) setting life rehabilitation as a goal becomes a way to maximize physical and cognitive performance, with possible longevity gains; (3) maintaining low staff to resident ratios provides residents with higher levels of interpersonal care; and (4) prioritizing experiences of seasonality and culture, ensures frail older people are better connected to the world beyond their walls.

All this, however remarkable, still leaves out an ongoing unresolved issue: the growing burden of home care, as half of the family caregivers are 65 and older with their own health issues.

Italy: As a national policy, Italy has a universal healthcare system which in theory provides seniors access to quality healthcare. The approach focuses on preventive care, medical services, and some specialized clinics for geriatric patients.

A study in the European Journal of Health Economics, “The residential healthcare for the elderly in Italy: some considerations for post-COVID-19 policies” (October 2021) finds that the uneven territorial distribution of nursing homes may have amplified the spread and severity of the COVID pandemic.

There is a long societal tradition of strong intergenerational bonds and familial closeness. While more so in the past, families still often continue to play a significant role in providing emotional and social support, minimizing feelings of isolation.

However, the high cost of living and economic aspects have heightened issues for many. A study in The Gerontologist, titled “Aging in Italy: The Need for New Welfare Strategies in an Old Country” discusses the impact of aging on economic sustainability. The high cost of living and difficulties in finding employment for those seniors wishing to do so have created difficult economic conditions. Pensions and social welfare programs do provide a modicum of relief but typically fall short of what is needed.

Such studies highlight some of the challenges faced by Italian seniors and suggest that there is a need for new welfare strategies to address these issues.

United States: Contrary to most Europeans, Americans rely on a mixed healthcare system that is more private than public. As such while it provides extensive medical research and facilities, but nonetheless, healthcare and access for seniors is heavily dependent on combined public/private health insurance and the availability of geriatric specialists.

Social support networks in this multicultural society vary but often rely less on family and increasingly on assisted living facilities and community organizations.

According to the National Council on Aging (NCOA), while Social Security benefits lift 16.1 million older adults above the federal poverty level (FPL), a larger number, 16.5 million age 65+ are economically insecure, with incomes below 200% of the FPL.

These older adults struggle with rising housing and health care bills, inadequate nutrition, lack of access to transportation, diminished savings, and job loss. Older women are also more likely to live in poverty than men as a result of wage discrimination and having to take time out of the workforce for caregiving. And over half of Black and Hispanic adults age 65+ have incomes below 200% of FPL

For older adults who are above the poverty level, life may not be all that easier: one major adverse life event can change today’s realities into tomorrow’s troubles.

Such persons are at risk of rising costs of living, which may place them at an economic disadvantage and potentially at lower levels of socioeconomic status (SES: a concept that encompasses not just income but also educational attainment, financial security, and subjective perceptions of social status and social class).

The majority of older adults do not work and have fewer options for continued income. In 2014, 61 percent of persons aged 65+ received at least half of their income from Social Security.

Another aspect with major ramifications is the extent of loneliness for American seniors.

According to a report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM), more than one-third of American adults aged 45 and older feel lonely, and nearly one-fourth of adults aged 65 and older are considered to be socially isolated.

Loneliness and social isolation in older adults are serious public health risks affecting a significant number of people and putting them at risk for dementia and other serious medical conditions.

Social isolation significantly increases a person’s risk of premature death from all causes, a risk that may rival those of smoking, obesity, and physical inactivity. And, as it goes hand in hand with poor social relationships, it is also associated with increased risks of dementia (about 50%), stroke (32%), and heart disease (29%).

While far from where it needs to be, there is growing awareness of the importance of senior care and new initiatives promoting healthy aging are gaining traction.

Snapshots of 4 “Not-So-Rich” Countries

Cuba: Fidel Castro began a process of providing comprehensive health services for its older population. Its healthcare system offers its citizens primary healthcare and prevention, and free health care, implemented by a well-trained healthcare workforce with expertise in geriatric care.

A couple of recent reports, one in The Journal of Latin American Studies “Healthcare in Cuba: Sustainability Challenges in an Ageing System”, and the other recently published by Springer (June 2023), “Ageing in Cuba: A Challenge for the Elderly’s Social Protection and the Organization of Care” surveyed the Cuban healthcare system, and found both strengths and weaknesses.

In particular, while the health sector was found to have adapted to the growing needs of the older segment of the population, tensions in the social protection system, particularly weaknesses in contributory pensions, resulted in the impoverishment of the elderly; meanwhile, shrinking social assistance schemes made it impossible to protect this particularly vulnerable group.

However, Cuba does provide institutional assisted living for older adults with a network of specialized institutions known as “Casas de Abuelos” or “Homes for the Elderly” – of which 300 were opened in 2020. These offer residential care for older adults and provide a range of services, including meals, medical care, recreational activities, and social support.

Broadly speaking though flawed, the system does a better job than most in caring for its elderly.

Egypt: This country faces multiple challenges in addressing the healthcare needs of its aging population. According to its Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS), life expectancy at birth in Egypt was 74.3 years in 2021, and the number of elderly persons (60 years and over) reached about 6.8 million, representing 6.7% of the total population.

A report by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) highlights the challenges faced by older persons in Egypt, including income, health, education, autonomy, and safety. The report notes that while the number of persons aged 60+ is expected to more than double between 2020 and 2050, there are concerns about the ability of national systems to address the needs of older persons.

Family is the primary source of support for older adults over the age of 75. In Egyptian culture, older adults expect to live with their adult children who look after them. In recent years, however, changing societal dynamics, economic constraints, and urban migration have disrupted the Egyptian family-based care system.

The pension system is insufficient: Those seniors with a pension find that it is typically inadequate to cover basic needs, especially with rising inflation and limited opportunities for those seniors who want to be employed.

Also, there is a limited number of geriatric care facilities compared to needs, and insufficient specialized geriatric training for healthcare professionals.

That said, there has been some recognition of the need for additional financial, institutional and public sector support with the Takaful and Karama programs, providing cash assistance to vulnerable older adults. Additionally, NGOs and community-based organizations play a vital role in providing social support, healthcare services, and financial assistance to older adults.

Ethiopia: This huge country grapples with numerous challenges in addressing the health needs of its aging population, different regions, and ethnic groups. The healthcare system in Ethiopia is primarily geared towards providing primary healthcare services for the general population, with gaps in specialized care for older adults.

The sense of collective responsibility and respect for elders is deeply ingrained in Ethiopian society. For people over 75 years of age, traditionally the family plays a crucial role in social and economic welfare.

Adult children are expected to take on the care and support of their aging parents, often living with them or in close proximity. However, with increasing urbanization, younger generations are moving away from rural areas, leaving their elderly parents behind.

This has led to a broader demand for public and non-profit groups such as faith institutions, to provide adequate care and support for older adults.

The World Bank, in a study about age-focused social safety nets in supporting older citizens, found that Ethiopia, despite achieving impressive economic growth over the past decade, remains one of the lowest-income countries in the world, with older citizens being among the hardest-hit members of the community.

This finding is confirmed by HelpAge International: The coverage of pension schemes in Ethiopia is low compared to other Sub-Saharan African countries, meanwhile, its aging population continues to grow.

In recent years, the government has made progress in implementing social protection interventions such as the Ethiopian Rural Productive Safety Net Program and the Urban Productive Safety Net Program. These programs cover a total of 8.6 million extremely poor and vulnerable citizens and have positively impacted their lives by enabling them to have access to food, health services, and social activities.

However, challenges related to targeting, transfer value, and timeliness of payment affect the elderly more than any other group benefiting from a safety net.

India: With the now largest population in the world, it has one of the largest numbers of elderly anywhere, facing major challenges in providing healthcare services. Its healthcare infrastructure remains insufficient, particularly in rural areas.

The lack of geriatric specialists and comprehensive health programs tailored to the unique needs of the elderly further contributes to the prevalence of age-related health issues.

Traditionally, older adults in India have relied heavily on their immediate and extended family for care and support in their later years. Family reliance continues to be a significant aspect of social and economic welfare for people over 75 years of age, especially in rural areas. Adult children are still expected to take responsibility for caring for their aging parents, both financially and emotionally, and multi-generational households are common.

Rapid urbanization and changing societal norms have translated into young people migrating to cities for work or for education. This affects the ability of families to provide care for their older members and as a result, it is diminishing.

Public sector engagement has a nearly thirty-year history. In 1995 the government introduced the National Social Assistance Program (NSAP). of which the Indira Gandhi National Old Age Pension Scheme (IGNOAPS) is one of five sub-schemes.

This effort was designed to provide a monthly pension to citizens aged 60+ and living below the poverty line. However, an audit conducted by the Comptroller and Auditor General of India (CAG) was devastating: It found improper use of funds, lack of a proper beneficiary database, age inaccuracies, disability pension mismanagement, payments made to deceased beneficiaries, and inefficient fund usage.

There are limited resources available for some government efforts, e.g. the National Programme for Health Care of the Elderly designed in theory to establish geriatric clinics, provide training to healthcare providers, and enhance access to healthcare services, but these are modest in comparison to the need.

India’s elderly population will continue to grow, as will the challenges this country faces. How well it does will have a major effect on all age groups and the success of its economy.

Complex matters, no easy answers

While some countries have made progress in this area, most need to pay greater attention to care for their aging populations. Nations can learn from each other’s successes and failures to develop and implement effective strategies for addressing the unique healthcare needs of older adults.

Investing in geriatric care infrastructure, training healthcare professionals, promoting health education, and focusing on community-based care, is a win-win solution.

This tour d’horizon examines the quality of life for people over age 65 in different country settings, underscoring the complex tapestry of factors that influence their well-being, and the difficulty in making firm judgments about the bad, the good, the best. Doing so might be of help for policymakers considering their situation, and possible changes to improve the lives of their elderly populations.

As older populations increase their demographic percentage virtually in every region, albeit less so in much of Africa, efforts to enhance healthcare services, social support networks, and economic support, will increasingly become critically important for governments and societies.

Failing to do so will be a costly mistake, not just for the seniors and their quality of life, but for the country writ large.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: Old Harari Woman, Harar, Ethiopia. Featured Photo Credit: Rod Waddington.