The upcoming UN COP26 is largely considered the last chance for humanity to avert catastrophic and irreversible impacts of climate change. However, rising tensions between richer and poorer nations threaten to derail negotiations. Rich countries have consistently fallen short on their pledges to provide financial assistance to those most vulnerable. Weeks away from the conference, Africa is demanding an effective climate finance tracker be established.

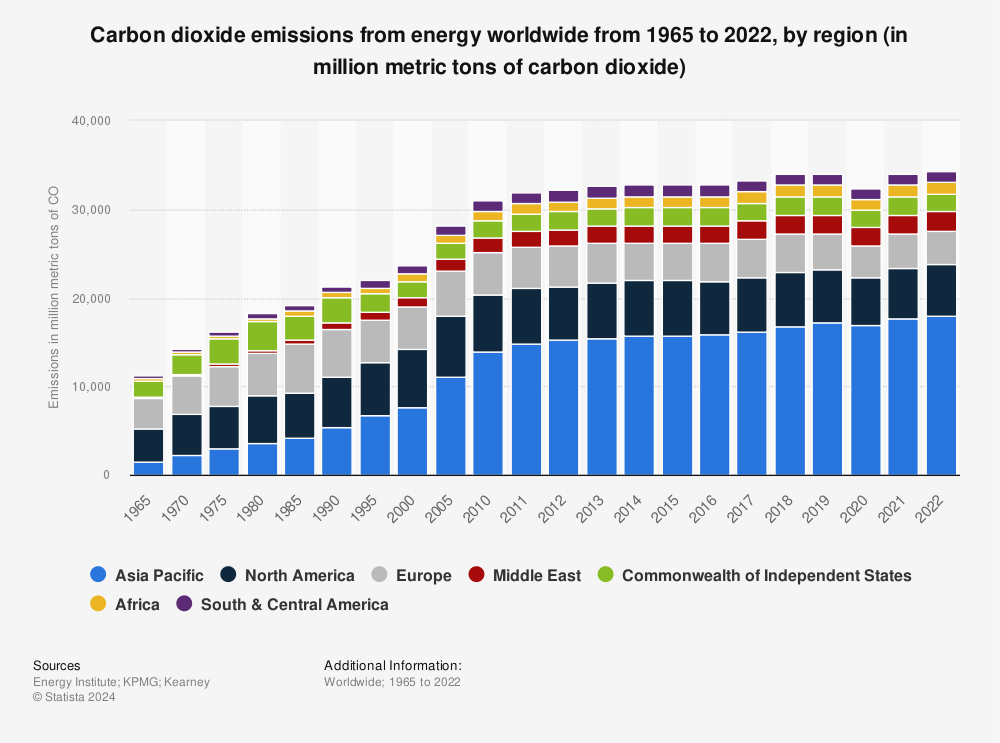

Africa, a continent ravaged by colonialism, emits less than 4% of annual global carbon emissions. Nonetheless, it is bearing the brunt of climate change’s most grievous damage. Temperatures in Africa are rising faster than the global average, total deglaciation is expected in the next two decades, and by mid-century the continent’s economy could shrink by 3% solely due to climate change.

The devastating toll of climate change isn’t an abstract future projection for Africans, it’s daily life. In 2020, amongst a global pandemic, the continent faced extensive flooding, the worst devastation from locusts seen in half a century and the continuation of a three year period of drought. For a region heavily reliant on agriculture, the effects have been catastrophic but are only set to get worse.

Africa's 3 snowcapped Mountains could see their glaciers disappear by 2040 due to global warming.The three mountains are;

🇹🇿Mt.Kilimanjaro 5895 metres

🇰🇪Mt.Kenya 5199 metres

🇺🇬 Ruwenzori Mountains 5109 metres pic.twitter.com/NlM8fHg8aL— Zoom Afrika (@zoomafrika1) October 21, 2021

African nations are footing a hefty bill for all of this damage. In 2016, an earthquake in Tanzania cost US$458 million in direct damages, whilst the cost of drought in Ethiopia came in at US$467 million. A report estimated that sub-Saharan Africa may have to spend $30-$50 billion, or 2-3% of its GDP, every year on adaptation to avoid even worse outcomes. Other studies have suggested that even for individual nations such as Nigeria, climate change could cost up to $460 billion by 2050. Estimations for the economic and human cost of climate change vary as new scientific discoveries and data emerge every day.

Who pays for this damage?

What is clear, however, is that Africa requires financial assistance and rich nations, with their history of polluting, are obligated to provide it. This has been known for decades and systems have been established to provide this aid, they just haven’t succeeded. In 2009, developed countries (as they are termed in the Copenhagen pledge) agreed to raise $100bn per year by 2020 to help developing nations curb their contribution to a warming planet and adapt to its ineluctable fallout.

Despite a decade passing and the intensified impacts of climate change clearly visible all around the world, rich nations have undeniably failed to meet these pledges. Poorer countries have been forced to pay the bills for pollution they did not cause, forgoing opportunities to develop and improve social welfare.

Although the rich nations pledged $100 billion per annum, the reality has been an average of $59.7 billion a year. Oxfam estimates that developed nations are still unlikely to meet the target by 2050, calculating that they will reach only $93 billion to $95 billion per year by 2025, five years after the goal should have been met. As a result, vulnerable countries will miss out on roughly $68 billion to $75 billion in total over the six-year target period.

Weeks away from the United Nations Conference of the Parties (COP26) in Glasgow, leaders across the world have increased their climate finance pledges. However, there is little to suggest that these promises will be kept any more than the previous ones. Climate negotiations are built on trust, yet few countries appear to have stuck to their targets and pledges, threatening the integrity of promises made in Glasgow.

The U.S. will double its financial support to $11.2 billion to help low-income countries adapt to climate change and shift to clean energy, Biden says at #UNGA https://t.co/85il5WuRSV pic.twitter.com/FUI4rgstul

— Bloomberg Originals (@bbgoriginals) September 21, 2021

The 2009 pledges may have been doomed from the beginning as no formal deal was established deciding what each country should pay. Africa wants to ensure these mistakes are not repeated at COP26 and is calling for an accurate and accountable climate finance tracker.

“We need to have a clear road map how they will put on the table the $100bn per year, how we can track (it),” said Tanguy Gahouma, Africa’s top climate negotiator. “We don’t have time to lose and Africa is one of the most vulnerable regions of the world.”

Related Articles: UN Warns That Countries Are Failing to Meet Paris Agreement Goals | Air Pollution is Leading Environmental Killer, Claiming 7 Million

A climate finance system in dire need of reform

Although the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) claims US$ 79.6 billion was delivered in climate finance in 2019, some analysts say these numbers are highly inflated. 80% of all reported public climate finance came in the form of loans and not grants, producing a climate debt trap. Roughly half of this was non-concessional and offered on ungenerous terms demanding higher repayments from poor countries whilst the full face value of the loans were counted in climate financing reports rather than their grant equivalent.

NEW REPORT: Over a decade ago, rich countries committed to mobilize $100 billion/year in climate finance to help developing countries deal with #ClimateCrisis…

But donors are over-reporting: the true value may be just 1/3 of that reported.

👉🏾 https://t.co/zUaTEg26qL pic.twitter.com/LNHfqVNRpQ

— Oxfam International (@Oxfam) October 20, 2020

Furthermore, rich countries have been repackaging Official Development Assistance (ODA) money as climate finance. Funding for education, transport and infrastructure is re-branded as climate finance. Although these projects don’t directly target climate action, the countries include them in their climate finance obligations.

As many rich nations fail to meet their paltry obligations of 0.7% GDP for ODA, they have now found a new way to cheat countries of financial assistance. This loophole has meant that Africa may actually be receiving less than they would in the absence of climate finance.

The problems with the current system continue. Much of the climate finance already provided has gone to mitigation efforts and projects reducing emissions. This has left a gaping hole in the financing of adaptation efforts which are pivotal for nations already facing the consequences of climate change. In 2020, 1.2 million people were displaced by storms and floods across Africa, a figure 2.5x higher than the amount fleeing due to conflict.

Donors may prioritise mitigation projects for their clear and measurable success or because the climate crisis debate has become myopically focused on reducing emissions at the expense of other issues. Politicians in developed countries often receive more praise for reducing emissions in international discussions whilst adaptation efforts only aid recipient countries. This narrow focus and desire for validation denies countries autonomy in the allocation of climate finance and may have dire consequences for their citizens. It might also be construed as a form of neo-colonialism, especially when the economic gains of mitigation projects are considered.

“Adaptation almost never is a loan-giving situation… If you’re giving poor people money to help them deal with the impacts of climate change, that doesn’t generate money.”

– Saleemul Huq, director of the International Centre for Climate Change and Development in Dhaka

Beyond this, much of the climate finance is allocated to middle-income countries, 20.5% went to Least Developed Countries and just 3% to Small Island Developing States.

“Many, many African countries are lamenting that they are not able to jump through the hoops [to access climate finance] because of the complexity and the technicality,” says Chukwumerije Okereke, an economist at Alex-Ekwueme Federal University Ndufu-Alike in Ikwo, Nigeria. “And they’re not receiving sufficient capacity-building exercises and training in this.”

What could reform look like

It is clear the current climate finance system isn’t working, which is why Gahouma, among others, is demanding action at COP26. African countries are asking for a more detailed and accurate tracking system, as well as an increase in funding and a distinct focus on adaptation funding. Many countries want to see finance allocated for “loss and damage” to help those experiencing irreversible losses that cannot be adapted to.

“The $100bn was a political commitment. It was not based on the real needs of developing countries to tackle climate change,”

– Gahouma said.

Alternatives have also been proposed. A new system could provide debt-for-adaptation swaps. This would allow repayment of current loans to be converted into local currency and spent locally on adaptation, boosting economies and saving lives.

Regardless of how it is done, it is clear that the climate finance system must be fixed. If there is any hope of climate justice, vulnerable countries can no longer bear the brunt of a climate crisis they contributed the least to. To ensure contributions remain low, countries must receive the required climate finance assistance to leapfrog fossil fuels and adopt sustainable technology. Moreover, climate finance is imperative to avert wide-scale humanitarian crises.

There can be no climate justice if restrictions continue to be imposed upon states most in need of development and least responsible for the current climate crisis. The last decade of inaction has sown irreparable distrust between poor and rich nations. If there is any hope of the global cooperation needed to combat climate change, monitoring systems will have to be put in place to hold countries that make pledges accountable.

COP26 may represent the last chance humanity has to take meaningful, unified action on the climate crisis. More ambitious targets must be set and more ambitious support and monitoring must be provided. If leaders can trust one another to do this, there may be hope for us after all.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: Man carries a United Nations folder. Featured Photo credit: Ilyass SEDDOUG