When you watch a terrifying or heartbreaking documentary, are you moved to do something more than just “share” the news on Twitter and Instagram? Here I will try to explore whether activist films and books are capable of moving people to take actual, effective political action. Because there is a lingering suspicion that we are simply confusing “hashtag activism” with activism tout court.

Participant Media, a major California-based film production company founded in 2004 by social entrepreneur and e-Bay cofounder Jeff Skoll, is a key part of his social enterprises and has produced so far more than 100 feature and documentary films that collectively have earned 74 Academy Award nominations and 19 wins. By 2012, Participant Media wanted to know what films spur people to take political action and what films don’t.

To find out, it developed, with assistance from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Knight Foundation, and the Annenberg school’s Media Impact Project, an interesting index intended to measure audience reaction. The New York Times covered it in a 2014 article explaining how the index works: It “compiles raw audience numbers for issue-driven narrative films, documentaries, television programs and online short videos, along with measures of conventional and social media activity, including Twitter and Facebook presence. The two measures are then matched with the results of an online survey, about 25 minutes long, that asks as many as 350 viewers of each project an escalating set of questions about their emotional response and level of engagement.”

Results, perhaps unsurprisingly, tended to show a gap between emotional response and taking action. Deeply moving films unexpectedly tank.

One film is highlighted in the New York Times: “The Cove” about the killing of dolphins in Japan. It sold poorly with only $1.2 million in ticket sales worldwide, a drop in the ocean (pun not intended). It seems activists were not keen to see the movie because of its gory content but are willing to “sign up”, said Chad Boettcher, Participant’s executive vice president for social action.

It appears that there is a disconnect here. And it raises the question of exactly how the Participant index defines “taking action”, especially in the Internet age. Because how many people watch a film may not be a good indicator of activism. Between watching and doing, there is a gap that may well be unbreachable in most cases, or not even relevant.

In the real world, away from the Internet, there are all sorts of ways to express political activism, from street marches to sit-ins to boycotts as well as more institutionalized forms, both illegal, like the famous Black Block in Italy, and legal like industry lobbies in Washington D.C.

Also, there are also different forms of activism, from “judicial activism”, a term introduced by Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., in a January 1947 Fortune Magazine article titled “The Supreme Court: 1947”, to environmental and climate activism, the latter having sprouted a new genre of literature, climate fiction.

Does the Participant index consider “hashtag activism” as “taking action”? Conventional wisdom has it that the Internet multiplies the speed, reach, and effectiveness of activism. So one shouldn’t count a reaction on Twitter or Facebook as the equivalent of “taking action”.

But the more interesting question is this: Is real-world activism really more effective thanks to tweets and Facebook “likes”?

This is an important point: “hashtag activism” is definitely on the rise, there have been many such campaigns over the decade.

Among them, the #BringBackOurGirls hashtag remains one of the highlights of this kind of activism. It came as a response to the May 2014 kidnapping of hundreds of young girls by the infamous Boko Haram in Nigeria that immediately garnered over 4.5 million tweets. Alas to no avail. Today, six years later, there are still too many girls missing.

More recently, in the same region, we got the news that hundreds of boys were taken from their school by Boko Haram militants and, remarkably, have been returned to their parents. Was it because of the earlier hashtag activism episode? Was it because they were boys and not girls? We’ll never know.

Yet there is a real danger that social media siphon activist energies off on the Net, giving people the illusion that they are being “active”. It’s just too easy to press that “share” button and be done with it. It’s also too easy to “sign” online petitions from Green Peace and Avaaz, maybe donating a few dollars via Paypal.

So can we expect more from literature, a “slow form” of art compared to films? “Slow” in the sense that it takes more time to “consume” a book than to watch a movie.

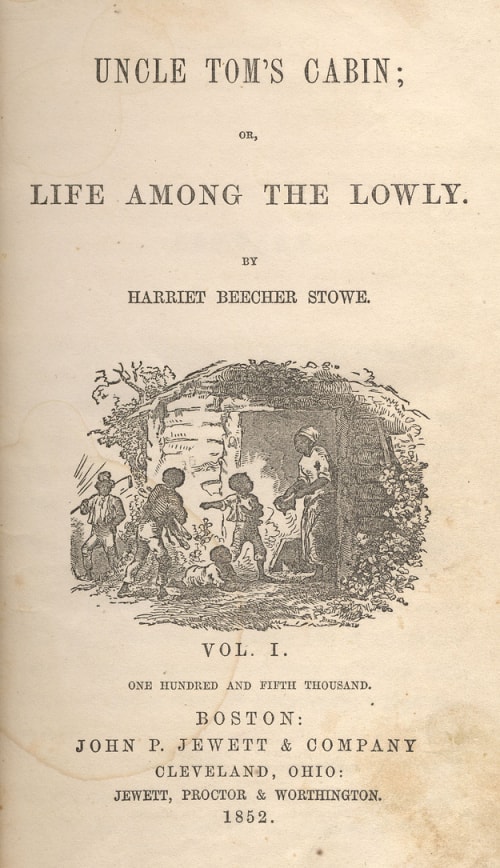

Historically, literary pieces are supposed to have stimulated political activism with extraordinary results. In the Anglo-American world, mention is always made of Uncle Tom’s Cabin as the novel that heralded in the American Civil War and the end of slavery in America. I say “heralded” because it may have changed the mind set of many Americans, but it is hard to prove a cause-and-effect linkage.

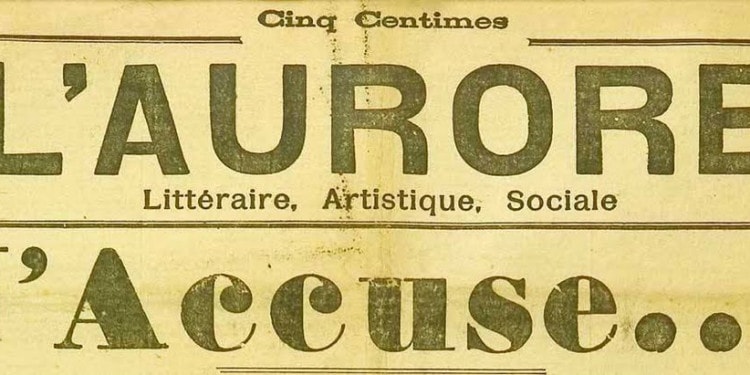

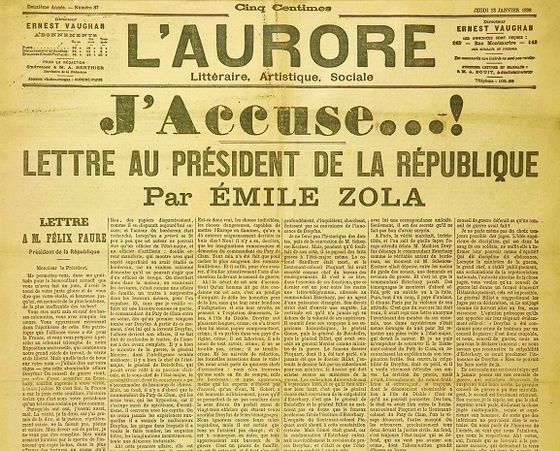

In France, what comes to mind immediately is the famous episode when author Emile Zola risked his career publishing his “J’accuse” on the first page of a Parisian daily, “l’Aurore,” accusing the French army of anti-Semitism and obstruction of justice.

But here too, it took time to obtain results. A lot of time.

That Zola letter published in 1898 helped to lead to Dreyfus’s liberation in 1889 but not his rehabilitation. The so-called “Dreyfus scandal” continued to divide the country between antisemites and those defending justice, for another 8 years, until 1906 when Dreyfus was finally fully exonerated and reinstated in the army.

And anti-Semitism lingers on in France to this day, indeed it is on the rise again:

In conclusion, the linkages between a film or a piece of literature and activism are both numerous and tenuous and, that is the main point, they take time to produce tangible results – things that go beyond a “like” on Facebook and a tweet. And it would seem that the time it takes might well be longer than a century or two…

First published in 2014. Updated 23.12.2020

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com.