In existence since 2018, the Global Preparedness Monitoring Board (GPMB) was established as an independent body upon the recommendations of a High-Level Panel on the Global Response to Health Crises. Co-convened by the World Health Organization and the World Bank, it is composed of leading experts from around the world and its structure and objectives mirror another famous UN expert panel, the UNFCCC that tracks climate change – with the difference that GPMB tracks public health.

More specifically, GPMB aims to track the level of global preparedness, i.e. the ability of all UN member countries to address the next pandemic. Because we know one thing for sure: In our globalized world, the next pandemic is a certainty even if the date of onset and the kind of disease are still unknown.

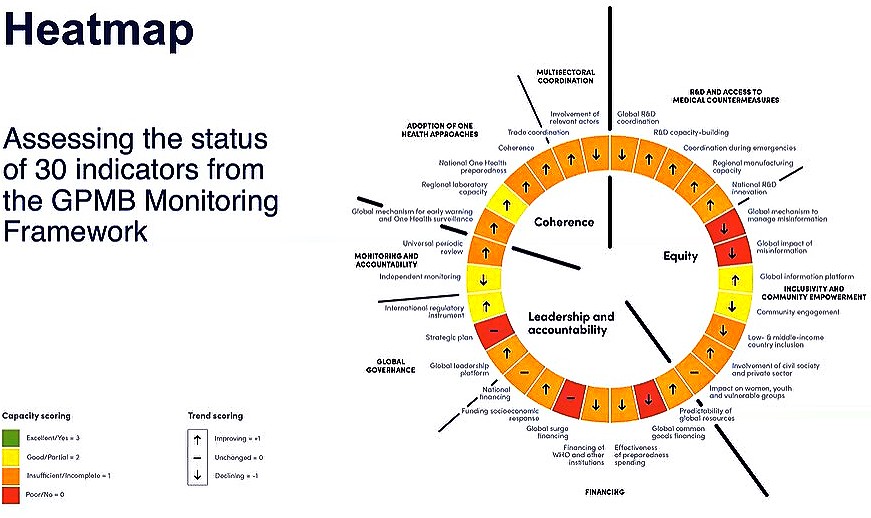

In its just-released third report, “A Fragile State of Preparedness”, significant weaknesses and declining capacities in several critical areas of preparedness are highlighted. The report is based on its monitoring framework with multiple indicators developed over two years. 30 indicators have been identified, relating to equity, leadership, accountability and coherence, each assessed by performance color ratings, as shown in the report’s heatmap below:

As Joy Phumaphi, GPMB Co-chair and former Health Minister of Botswana stated, “Not one critical capacity for preparedness was assessed as fully met in this Report, which is deeply concerning and disappointing.” A point repeatedly and eloquently echoed by the other GPMB Co-chair, former President of Croatia, Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović at the press briefing.

Indeed, the heatmap tells a devastating story about global preparedness (or lack of it). Not one of the indicators shows green (i.e. excellent) and just five are yellow (i.e. good or partially achieved). Most are orange (insufficient or incomplete) and five are red (poor). Likewise, the arrows indicating the trends for each indicator show us a paralyzed world, substantially unprepared to address a pandemic. And we are indeed talking about the world here, for this monitoring mechanism is the only one that covers the whole world, both globally and at the country level.

In short, out of the 30 indicators used in this year’s assessment, 16 show some improvement, 10 show diminished capacity compared to the baseline, and four indicate there has been no progress. The weakest areas relate to financing, global R&D coordination, global management of misinformation and disinformation, and inclusion of all relevant actors and countries (details are provided in the report appendix).

Yet, all things considered, it is a very good and rich effort, including its realistic assessment of the impediments to future progress. Also commendable is its recognition that One Health, the interface between humans, animals, plants, and the environment, has not been adequately integrated.

Recognition of the role of One Health in pandemic prevention, preparedness and response

The Report drily notes that “many One Health activities have been focused on a particular human disease, such as influenza; neglected zoonoses, such as rabies; or emerging One Health priorities, such as antimicrobial resistance.” Implicit is the recognition of the key role One Health could play in medical research as it contributes to building up knowledge of “neglected zoonoses” or emerging issues such as AMR which could have catastrophic impacts in a new pandemic situation.

More importantly, the GPMB experts make the point that a “fully integrated approach”, i.e. One Health, would be fundamental for achieving an effective level of prevention, preparedness and response, stating:

“A broader perspective would consider animal health in a more genuinely integrated way alongside human health as fundamental capacities for pandemic prevention, preparedness and response (PPPR). Only when this fully integrated approach is taken will One Health activities have the scope and capacity to assess and respond to the needs of prevention and early warning across a broad range of diseases. and in its realistic assessment of where we are and impediments to achieving great progress.”

The problem is, however, that One Health is not yet “fully integrated” either in medical research or in the implementation of PPPR measures and that is a serious shortcoming the GPMB experts have recognized.

Report findings and recommendations:

Given its assessment of One Health as potentially playing a key role in PPPR, the GPMB experts recommended further integrations of the One Health approach to achieve effective pandemic prevention, preparedness and response.

Turning now to the Report’s other major findings, they can be summarized as follows:

- Monitoring and accountability have been insufficiently resourced and institutionalized. There is a need for independent monitoring to complement self-assessment and peer review, at all levels, nationally, regionally and globally, as a basis for more equitable distribution of human, financial and infrastructure.

- Global financing of pandemic prevention, preparedness, and response is woefully inadequate, inefficient, uncoordinated, and insufficiently aligned to country needs and processes. Countries struggle to make investments due to shrinking budgetary spaces.

- Global governance has been slow although it is evolving with key developments including the negotiations of a WHO Pandemic Agreement, and potential amendments to International Health Regulations.

- Medical research is globally insufficient and innovations may not be delivered equitably: Limited national and regional R&D capacities leave countries dependent on a global system that cannot ensure equitable distribution of innovation; coordination of pandemic-related R&D at the global level is also weak.

- Misinformation and disinformation contribute to the global trust deficit. Yet there is currently no global mechanism to effectively address health-related misinformation and disinformation.

- Global coordination has critical weaknesses including coordination across sectors beyond health, equal participation of all.

- Inclusivity and community empowerment are now at risk: Initiatives to enhance community engagement made during COVID-19 no longer find sufficient support now that the urgency of the crisis has faded. Improving equity as the Health Minister of Bhutan said three weeks ago is imperative:

In light of the above weaknesses in global preparedness, the GPMB lays out four key priorities for action:

- Strengthen independent and multisectoral monitoring and accountability;

- Reform the global financing system for PPPR;

- Achieve more equitable and robust R&D and supply chains;

- Enhance multi-sectoral, multi-stakeholder engagement.

In short, the world is not prepared for the next pandemic: PPPR management, at the global, regional and national levels, is uncoordinated, chaotic, unresponsive, and underfunded. The GPMB recommendations systematically address each issue and are worthy of attention and require priority action from all stakeholders, public and private.

As Joy Phumaphi, GPMB co-Chair, said:

“Our report demonstrates that, although the state of the world’s preparedness is fragile, it is not without hope. There are many efforts underway to strengthen preparedness – but they will fail without the right resources and support. Leaders must double down on their commitment to learning from the lessons of the past and creating a world where we are all safe from pandemics.” (bolding added).

That said, GPMB findings could have benefited from:

- Attention specifically to monitoring research laboratories where potentially dangerous pathogens are being studied, and risks of error are significant.

- Greater consideration and support for “prevention”. The U.S Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in its “Interventions to Reduce Risk for Pathogen Spillover and Early Disease Spread to Prevent Outbreaks, Epidemics, and Pandemics” describes it this way:

“The risk of pathogen spillover and early disease spread among domestic animals and humans…can be reduced by stopping the clearing and degradation of tropical and subtropical forests, improving health and economic security of communities living in emerging infectious disease hotspots, enhancing biosecurity in animal husbandry, shutting down or strictly regulating wildlife markets and trade, and expanding pathogen surveillance.”

Indeed, many consider prevention to be the most effective option to mitigate the huge costs of preparedness and response to an infectious disease that can morph into a pandemic. Among them, the AVMA One Health Initiative Task Force made an urgent call for action in a report recently published by the American Veterinary Medical Association (Volume 233, Issue 2).

Will the GPMB report’s valuable recommendations be implemented?

It is simply hard to be optimistic. There seems increasingly less appreciation and willingness by the global community writ large, to put among its highest priorities the threat of a future infectious disease outbreak.

As a result, we are not much better positioned now than before COVID to act collectively. On the other hand, some regions and countries will surely do better.

This state of affairs reflects a multitude of both direct and indirect causes: for example, the exploding number of demands and political unrest faced by many Global South leaders make it difficult for its leaders to address future threats.

This is further exacerbated when Global North donor constituencies convey an almost “mission accomplished” sense with regard to COVID, brought on by extraordinary technological breakthroughs. Technology has shifted COVID from an urgent unknown to dealing with it as another disease for which there exists a vaccine, containment and treatment.

At the same time, other global priorities have attracted greater donor support because many economies are slowing down and reducing resources for assistance. While in some regards this is understandable, it is nevertheless shortsighted.

Further, despite more vocal and visible support for more active multiple engagement sectors, there is insufficient “walking the talk”. Properly, WHO has majority ownership of these matters, but tends to leave less space for others to focus on other aspects, such as that of a One Health approach, as well as the funding imbalance between prevention and response.

The report rightly points out that geopolitical tensions, and competing power structures seeking spheres of influence, coupled with increasing movement away from globalization and the post-World War II global framework, make public health cooperation less possible.

Decoupling, now sometimes referred to as “derisking”, is not just happening in trade and economic relations, but in systemic alternatives to public health. While different approaches can be productive, the lack of common cause in addressing emerging or reemerging infectious diseases cannot benefit anyone.

Maybe the wise voices of the GPMB experts will be heard and acted upon this time, for the benefit of all of us.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: This inca rope bridge is the featured image on the GPMB report, exemplifying the strength of community engagement: Called Q’iswa Chaka (Quechua for “rope bridge”) it is made of grass and is the last remaining Inca rope bridge, reconstructed every June; it spans the Apurimac River near Huinchiri, in Canas Province, Quehue District, Peru. Photo courtesy Rutahsa Adventures www.rutahsa.com – uploaded with permission by User:Leonard G. at en.wikipedia – cc license