Most of us live in a very troubled, interconnected world, one in which wars and civil strife are our daily diet. There is at least one place that has been somewhat removed from such widespread chaos, assuredly by no means entirely, but to a much greater extent – to the point that it offers an alternative model: Bhutan.

This is a landlocked country bordered by two giants, on one side China and the other India, the proverbial “between a rock and a hard place”. It has limited extractive mineral wealth, an economy that is dependent on relatively smallholder agriculture, and consumer and industrial imports mostly come from India. Its military outlays are modest: a small standing army and no air force or navy.

Given what many would consider major impediments, it has navigated the global political and troubled seas by staying relentlessly neutral, avoiding big power pressures, and chartering its own course for national survival and development.

The core of Bhutan’s foreign policy has been to avoid direct involvement in great power politics. It has been fruitfully learning from others what not to do, as for example, from other entities in the region such as Nepal.

It is also a place where its population respects its natural wonders that are not unduly disrupted by modern commercialism (disclosure: This is something I was able to see for myself on a recent trip to the country).

Bhutanese roads have no signs advertising products or services. Cows on the road must be shooed away to allow traffic to continue. Noise pollution from horns honking is a rarity. Likewise, the absence of aggressive road rage is notable and most drivers I’ve seen systematically show courtesy to allow drivers to get ahead. Hurry is not the overarching priority.

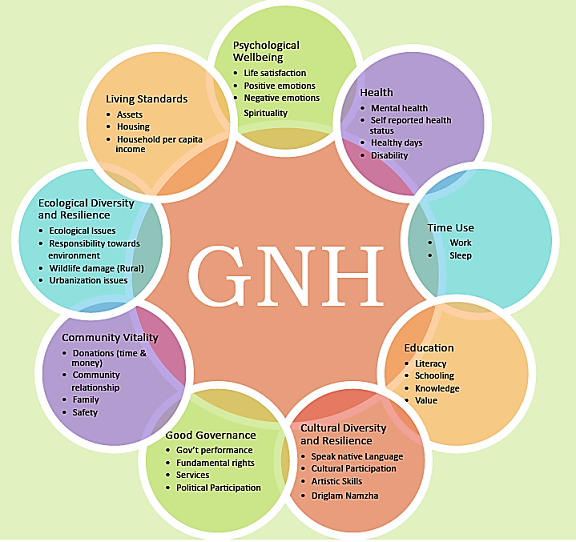

Despite such “lapses” of modern measures of national drive and strength, Bhutan has found a different kind of life vision. It has famously created the notion of the Gross National Happiness index and is the first country to achieve carbon-neutral status. It is actively pursuing a One Health approach to better protect its people, animals, plants, and the environment.

Why is this so?

Certainly, there are unique factors that have been either the cause or contributors to Bhutan’s pursuing its own pathway. The country has a long history of Buddhist culture and traditions and enjoyed political stability for over 120 years thanks to a monarchy whose leadership is still largely respected. The political acumen displayed by the monarchy coupled with past wisdom has made possible a timely move to a constitutional democracy whilst retaining a committed and concerned monarchy. This only began in the twenty-first century and early on in the transition the Bhutanese King put it in context, in an article published last year in the Druk Journal:

“Now, if we want our democratic system to work, if we want a democracy that will fulfill the aspirations of our people, then we must take the next step – we must adopt the ideals and principles of democracy. We must build a democratic culture. This period when democracy takes root is a slow process. It takes time. But this process is crucial for the ultimate success of democracy in our country.”

It seems his words have been heeded by his government and his people. It also helps to implement major societal changes that the population is small and homogeneous, roughly 770,000 people, not much more than the size of Washington, D.C.

What makes it different?

When the focus of international institutions and countries everywhere was on the gross national product (GDP) and other concrete data such as public and private levels of investment to measure national success, it became clear to Bhutanese leadership that their country could never hope to compete on those terms. And they realized that if they tried to do so, it would be at the cost of their Buddhist traditions and national character.

For whatever reasons, the idea was that all such indices missed the core of what is most important and bears on the human condition, and no doubt that is where Bhutanese people have reason to be proud. They invented the gross national happiness index (GNH), which is now a measure regularly assessed and refined by the United Nations.

There are and will be those who disagree or quibble with the indicators and whether Bhutan deserves a high rating. And even if there is currently an outflow of young people moving abroad, many to Australia, the image of a “happy” Bhutan is still largely true. That many young Bhutanese want to go to Australia may have something to do with the remarkable success of a Bhutanese-made film, Lunana: a Yak in the Classroom. Oscar-nominated in 2019 the film is about an aspiring singer who teaches kids in a remote school (Lunana is a real place) while dreaming of getting a visa to relocate to Australia.

Another difference that sets Bhutan apart is that it is the first carbon-negative country, with its vast forests absorbing more carbon dioxide than the country emits from all activities.

Forests cover over 72% of its land. And they are protected by the country’s constitution which mandates that at least 60% of its land remains forested for generations to come, naturally enhancing carbon sequestration.

Moreover, the country’s rivers generate far more low-carbon hydroelectricity than it needs for its own use and it regularly exports the surplus to neighboring countries. Over 80 percent of the nearly 11,000 GWh of electricity Bhutan generated in 2021 was exported, thereby helping to reduce regional emissions. In Bhutan’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) the possibility of offsetting 22.4 million tonnes of CO2 emissions in the region by 2025 through its export of hydroelectricity is highlighted.

While it remains committed to its traditions and its natural heritage, Bhutan is also looking to the future potential for carbon markets as a way to improve its finances and is intent on refining its data to do so.

It has also shown concern regarding the interface between humans, animals, plants, and the environment and issued the 2017 Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) establishing its One Health Strategic Plan to prevent emerging or reemerging infectious diseases.

Supporting its commitment, Bhutan was among the first countries to receive financing from the World Bank/WHO Pandemic Fund for strengthening its One Health efforts. A total of $42 million in combined grant, co-financing and co-investment will help to operationalize the One Health secretariat, strengthen surveillance and early warning, and upgrade laboratory systems. It represents a significant commitment to pursue One Health implementation.

Yet not everything is perfect

To err is commonplace for all countries, and Bhutan has made some missteps: Following a very effective two-year COVID lockdown period, the tourist industry, hotels, restaurants, and important sites were severely affected and limited tourists coming to Bhutan at least in part because the government raised tourist fees to very high levels. These were quickly reduced to a more reasonable level.

Further, the capital Thimphu is clearly in need of implementing an existing city plan done years ago and greater investment and attention to its urban services. Also, there are signs of increasing alcoholism and drug use. But these challenges pale in comparison to the many successes and certainly compared to what is happening everywhere else.

Note: I recently visited Bhutan and was fortunate to be in the hands of an expert guide with Bhutan Tashi Pelbar Adventure (for contact: bhutantashipelbar@gmail.com). Extremely knowledgeable, sensitive to abilities and needs, honest and courteous, it was an extraordinary window on Buddhism and Bhutanese society. I would strongly recommend others doing so and would happily go back.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: Ancient fortress (Dzhong) built to defend against Tibetan invaders Source: Author image