Climate fiction has recently gone viral because of the issues it is linked to: climate change and global warming. These are issues that come to the forefront of the news every time the United Nations releases its latest report on climate change through its Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPPC), igniting a debate between the climate activists and the deniers. And the debate couldn’t be more “heated” (no pun intended) than in America – most recently when the National Climate Assessment was released, confirming what scientists on the IPPC had long pointed out. Polar ice is melting, even on Antarctica, and it looks like now that there’s no turning back.

Climate fiction or “cli-fi” for short, has been drawn into the action by activists who hope that emotional cli-fi narratives will be far more effective in waking up the public to the need to reverse current trends than an IPPC string of scientific data projections. And, as reported by the New York Times, cli-fi is already put to use in some American universities to sensitize college students about environmental issues and how to handle them.

Paul Souders/Corbis in report of 2014 National Climate Assessment

Paul Souders/Corbis in report of 2014 National Climate Assessment

Indeed, it’s no coincidence that the term cli-fi was coined by a climate activist and journalist, Dan Bloom, currently based in Taiwan (see interview on Impakter). He coined the term back in 2008, noting that a number of books that appeared to be science fiction actually addressed climate issues. His observation was subsequently confirmed by Professor Adeline Johns-Putra, chair of the Association for the Study of Literature and Environment in the UK and Ireland. She told the Financial Times that she saw this as a definite trend: until the 1990s, there were “only a handful of novels” using climate change as a setting, she said, but since 2006, some 150 have made it into print, “including at least 50 in which [climate change] is a central theme.”

The term really took off in the US when one major American scientist, Judith Curry, Chair of the School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences at the Georgia Institute of Technology, wrote about it on her much-followed blog in 2012 (see here). NPR immediately interviewed her and the media gates were opened to a flood of articles, from the New York Times to the Huffington Post, the Christian Science Monitor, and the New Yorker in the US, and on the other side of the pond, the UK Guardian and the Financial Times.

All touted cli-fi as a new genre and gave their own version of what it is.

So what is climate fiction?

There is a wide range of opinions. Some see it as a sub-genre of science fiction, “essentially dystopian visions of a world decimated by climate change” (the Huffington Post) and “a subgenre of dystopian fiction set in the near future, in which climate change wreaks havoc on an otherwise familiar planet” (Wired Magazine). In short, a not-so-new form of apocalyptic literature.

Others see cli-fi as a self-standing genre (UK Guardian), even literary (Christian Science Monitor). For Cli-Fi Books.com, a website that showcases cli-fi novels and is funded by a small press specialized in climate fiction, the definition is yet broader, and involves climate change fiction and/or science fiction and can be speculative and literary, “ not necessarily always set in the future nor always apocalyptic”, “wildly creative and inventive”, “ reactive and proactive”, “open-ended.”

It could deal with any kind of climate change, warming or cooling, in the distant future or not -so-distant, even happening now like in Barbara Kingsolver’s novel, Flight Behavior, featuring an invasion of millions of monarch butterflies in the Appalachian Mountains, surely brought on by climate change.

Or it could have a broader scope and involve eco-disaster and global collapse.

In fact, there are fiction genres that bear those names and a quick search on Amazon turns up a surprising number of titles in some of them:

- eco-disaster fiction: 7

- collapse fiction: 366

- climate change fiction: 653

- climate fiction: 741

These numbers refer to a search done in May 2014 and they are of course merely indicative of the genre’s importance, since the lists are derived from the keywords used by authors in uploading their books. Still, of all those genre names, climate fiction comes out the clear winner – though one suspects the reason for the success may have something to do with the fact that the term is short and catchy.

More to the point, the success of this new genre is clearly linked to three facts:

- it is widely talked about in the media and recent cli-fi books tend to be best sellers;

- big name authors have published cli-fi novels, not just Barbara Kingsolver but also Margaret Atwood (Maddaddam), Michael Crichton (State of Fear) and Ian McEwan (Solar);

- it is a fast-moving, dynamic genre attracting new, and often young writers, like Daniel Kramb with From Here, Nathaniel Rich with Odds Against Tomorrow and Paolo Bacigalupi with The Windup Girl; the latter has drawn the attention of a major publisher, Knopf who acquired his next novel.

At least one major publisher – Knopf – is interested and involved in the new genre.

In short, the future of climate fiction looks very promising. Although cli fi has yet to produce the Next Great Novel on the scale of Orwell’s 1984 or Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, in due course, this will most certainly happen. Because we are all directly involved: this is the future awaiting us if nothing is done to reverse current trends.

What we need now is a cli-fi equivalent of “Big Brother is Watching YOU!”

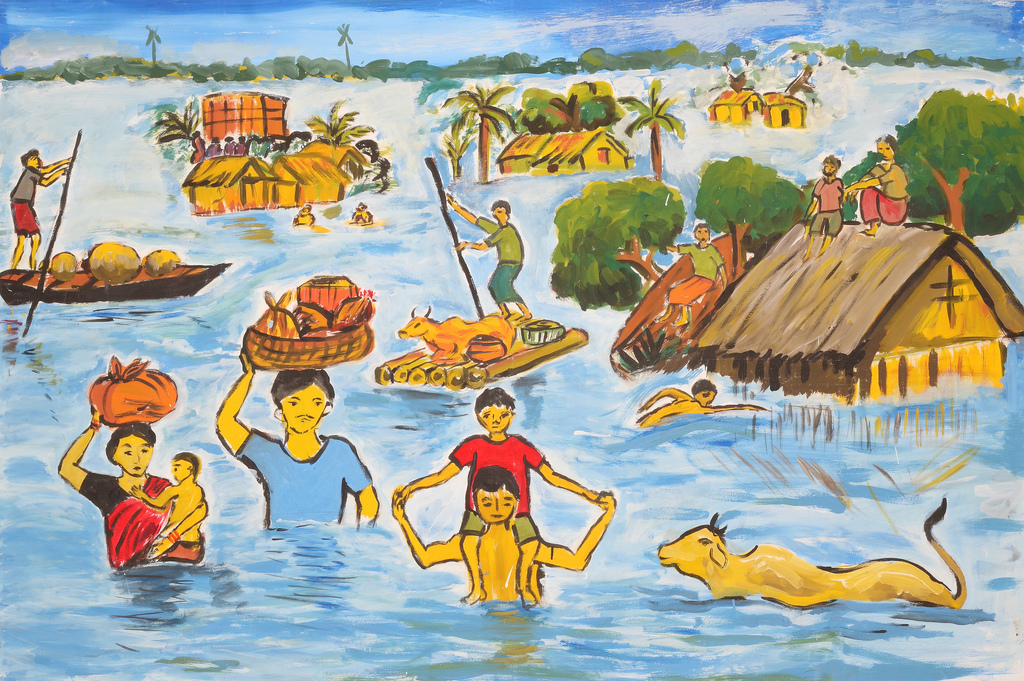

Photo credit: Bangladesh – climate change canvas (Photo credit: Oxfam International https://www.flickr.com/photos/8470194@N02/3057841579)

(Photo credit: Paul Souders/Corbis in report of 2014 National Climate Assessment)