Have you been wondering why the egg aisle in the supermarket is currently full of empty, ransacked boxes and – if by the off chance there are any eggs left – they’re much more expensive than before?

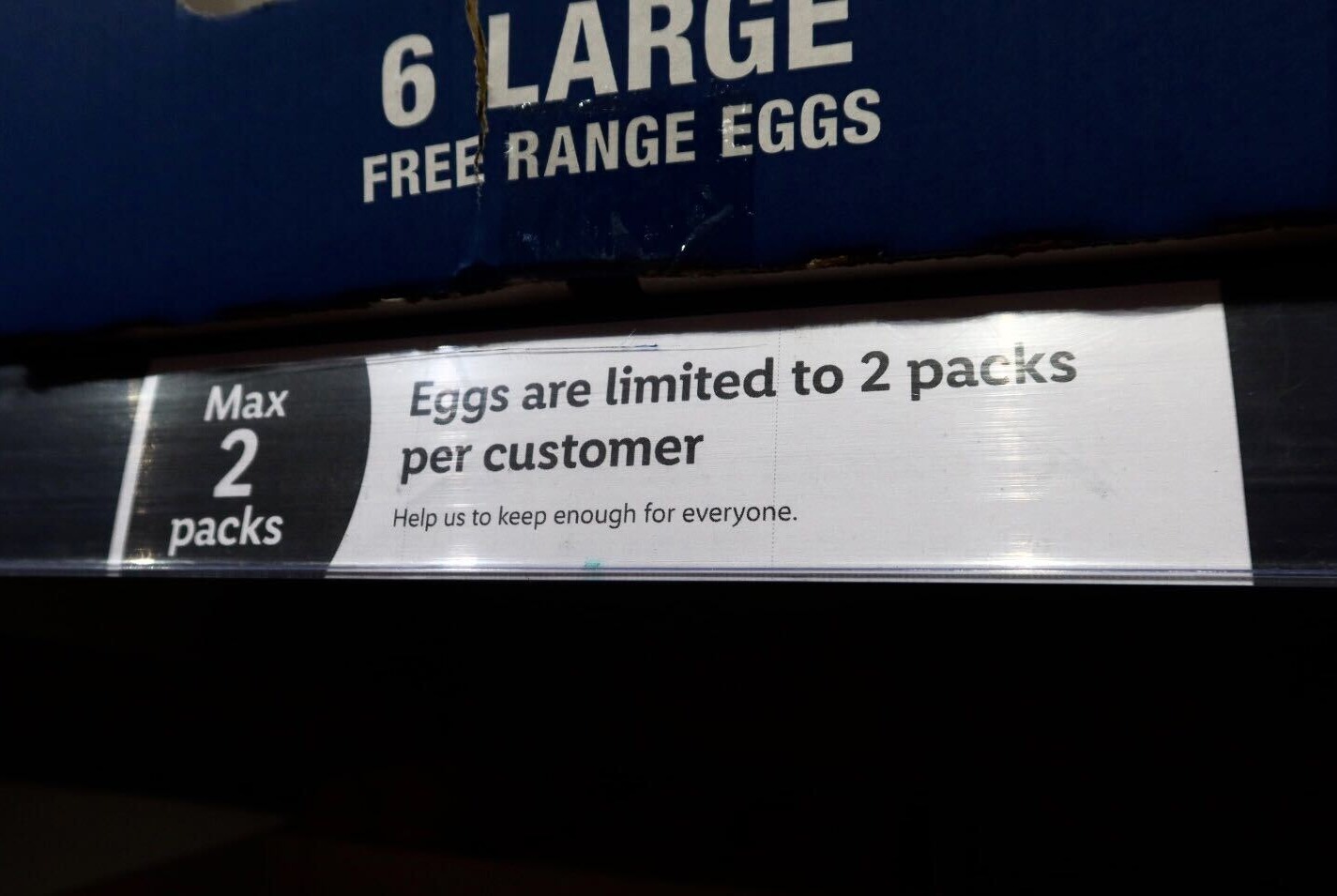

The end of 2022 and beginning of 2023 has witnessed the worst bird flu outbreak on record, resulting in supermarkets having to ration egg sales at the checkout and ramp up their prices by 60% in the US and 27% in the UK over the past year.

Avian Influenza, also known as bird flu, has been affecting birds across the world periodically since 1997 when it had its first outbreak in China and Hong Kong. There have since been three major outbreaks, and the most recent one has been going on since 2018 up until the present day.

The current outbreak has led to the death of 97 million birds globally, and if not taken seriously, can be fatal for humans too.

The first time the virus was detected outside of China was in 2003, and according to a recent report from the World Health Organisation, has caused 868 human infections so far, 456 of which have been fatal.

If this has been a problem for so long, why are there suddenly so few eggs?

The current outbreak of bird flu is the worst that the US, Europe and UK have ever seen. This epidemic has affected 37 European countries and has crossed the Atlantic for the first time as birds have migrated for winter, which is why Canada and the US have also suffered.

In addition to this, Ukraine is a “major exporter” of wheat and corn, and due to the war-related decrease in exports, chicken feed prices have escalated, in turn making eggs more expensive.

Bird flu commonly occurs in Europe in the autumn, and tends to die down again by the time we hit the deeper winter months. However this year, for reasons still unknown, the bird flu outbreak has continued to be particularly rampant and has led to widespread egg shortages in western Europe, most prominently in the UK.

What is being done to combat the problem?

During this major outbreak, governments have asked farmers to house their birds, keeping them inside to stop the virus from spreading.

This is why there has been a particular shortage of free-range produce, however the system is still far from flawless.

Currently, eggs cannot be classified as free range if the chickens have been inside for more than 16 weeks – that’s four months!

The UK and EU have therefore granted this timespan as a “grace period,” meaning that farmers can still label their eggs as free-range so long as the “housing order” is in action for less than 16 weeks.

Anytime that birds spend inside after the 16-week timespan must be put on the label of the produce, as battery farmed.

Related Articles: Avian Flu and the COVID Connection | It’s Time to Rethink How We Live With Animals | Why One Health is Key To Address Future Pandemics

Although this 16-week limit can regulate the label of the eggs, it shouldn’t go unnoticed that four months is a considerable amount of time.

It is also only on eggs that farmers have to change their label after this 16-week period, when we are talking about bird meat, it is a different story.

Birds that are raised for eating are usually slaughtered at 8 weeks of age, meaning they never reach the bracket to be classified as barn- or battery-raised.

So a bird may have never been outdoors in its life, but in this current state of affairs, still be classed as free range. Not to mention the difference in price between battery-farmed meat and that of free-range produce.

As well as the US and UK, France is also one of the countries suffering the sequel to the bird flu epidemic.

France’s egg production has decreased by 8%, yet prices have doubled, leading the country’s food industry to change its recipes for eggless alternatives such as changing the type of eggs used, switching to vegan proteins, or simply reducing the quantity of eggs used in the recipe.

This outbreak has come at a time when demand is particularly high for eggs, as they are cheap protein alternatives to meat in a period when there are few options to avoid soaring food prices.

Although Britain and the US are the countries worst affected by it, the issue has gone global, with Malaysia’s egg shortage setting Indian hatcheries on a path for record exports, and New Zealanders “rushing to buy their own hens.”

An outbreak of #avianInfluenza has been reported in a zone in #Niger for the first time since 2017, via #WAHIS. 500 poultry birds were killed to stop the spread. Control measures have been applied to prevent new outbreaks.

Consult the full report: https://t.co/tTnCBPyJZb pic.twitter.com/mlyvR0nZHl

— World Organisation for Animal Health (@WOAH) January 21, 2023

It’s not just our egg consumption that has taken the toll

The outbreak at present has affected 80 varieties of bird species. Professor Iqbal from the UK’s Pirbright Institute has told the BBC the outbreak has “killed 40% of the skua population in Scotland, and 2000 Dalmatian pelicans in Greece.”

Furthermore, veterinary expert Dr Louise Moncla of the University of Pennsylvania in the US has said that the virus is now spreading to mammals such as seals and foxes.

As such, farmers within the UK are still being asked to keep their birds indoors, as it is unknown when this epidemic will come to an end.

An outbreak of avian influenza on a mink farm in Spain provides the strongest evidence so far that the H5N1 strain of flu can spread from one infected mammal to another, @Nature reports:https://t.co/DCWSxAGhkT

— Lauren Pelley (@LaurenPelley) January 25, 2023

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: Eggs. Featured Photo Credit: DDP/Unsplash