The French presidential elections is a striking case of the “crisis of the left” that has been dragging on for decades in European politics – with notable exceptions (there are always counter-examples) of Antonio Costa‘s Portugal and especially Olaf Scholz‘s Germany that could count on a lively green party. Not the case in France where the greens – led by Yannick Jadot, who, despite his carefully and collaboratively constructed “ecology” programme calling for an “economy to fight climate change”, did not manage to attract more than 4.6% of the votes. And where French President Macron, vying for a second mandate, has presented himself as right-of-center.

Now with the first round over with yesterday’s elections, the two contenders left in the ring for the final round coming up on April 24 – two weeks from now – are exactly those everyone expected, and those than ran against each other in the previous elections, in 2017: President Macron and Marine Le Pen.

Setting aside the plethora of smaller parties and the fact that in France the greens don’t count, the first round of French elections gave us a few surprises: The classic panorama of French politics was changed, widening the gap between left and right. What we now have is a new, more radical left led by Jean-Luc Mélanchon and two major parties on the right led by President Macron and Marine Le Pen.

But let’s look at the changes in more detail and see how the second round might be played.

First-round election results: Macron vs. Le Pen and a collapse of the classic left and classic right

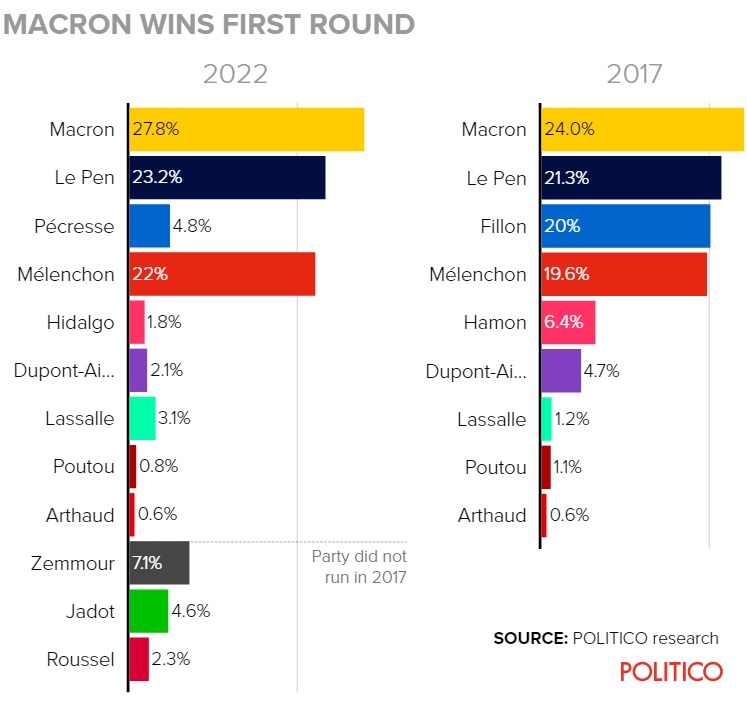

The classic left collapsed: For many, the extent of the collapse came as a surprise, the extraordinary fact that the socialist party led by former Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo only managed to get 1.8% of the votes when back in 2017 Hamon had gotten 6.4% of the votes – that too surely had not been a good performance but a better one than Hidalgo’s.

Still, the left is not gone, on the contrary. It did have a champion: Jean-Luc Mélanchon, a radical leftist with his France Insoumise (unbowed France) to the left of the Socialist party who improved from 19.6% in 2017 to 22%, nearly unseating Le Pen. A couple more points and he could have done it; if that had happened, we’d have a more normal political scenario with the left against the right.

As it was, in this first round, we had two kinds of right confronting each other: a more moderate one embodied by President Macron who, from his original center position had swung to the right – no doubt in an attempt to counter Marine Le Pen’s rise; and three major right-wingers, in this historical order:

- The biggest party was the Trump-like national sovereignty Rassemblement national (national rally) of Marine Le Pen; it’s worth recalling that in the first round of the Presidential elections in 2017 she got 21,3%, doing much better than her father, Jean-Marie Le Pen who famously shook up the French political scene in 2002 when he got 16,9% against incumbent President Jacques Chirac’s 19,9%;

- Followed by the Gaullist and moderate one of Valérie Pécresse’s Républicains, the successor party to the coalition that stood up against Jean-Marie Le Pen in 2002, sending him home in the second round and confirming Chirac as President; and

- the extreme-right, anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim new Reconquête party founded last summer by media pundit Éric Zemmour, an unexpected newcomer in French politics who appeared to threaten Marine Le Pen’s supremacy on the right.

Now that the results are in, we know that Valérie Pécresse didn’t make it: Just like Hidalgo, or perhaps worse than her, Pécresse suffered a crushing defeat, she obtained only 4.8% of the votes compared to her predecessor, Fillon’s 20% in 2017. That’s a huge difference and she didn’t even get to the 5% cut needed to have her campaign expenditures refunded. Neither did Hidalgo for that matter, they are both in deep trouble, both politically and financially.

The other remarkable thing about this first round was Zemmour’s rapid rise, probably explained by the youthful enthusiasm of his following: Despite Zemmour’s patriarchal looks (and in that he resembles another pundit on the left, in America this time, Bernie Sanders), he managed to appeal to a younger generation of voters often coming from socialist backgrounds and thus, in rebellion against their leftist parents.

As it turned out, Zemmour did not hurt Marine Le Pen’s campaign. On the contrary, by concentrating on the “classic” Le Pen issues – anti-immigration, anti-NATO, anti-European, and pro-French nationalism – he freed her to concentrate on pocketbook issues close to the heart of the French electorate worried about the cost of living crisis caused by the rise in fuel prices. That undoubtedly won her extra votes, especially among those who feel President Macron has abandoned them, starting with the Yellow Vests protesters that since 2019 have never really stopped.

In short, thanks to Zemmour, people forgot Le Pen’s dangerous agenda of leaving NATO and shaking up the European Union: There is no doubt that without France, the European dream would not survive, we would have a chaotic, divisive “Europe of nations”.

However, one of the surprises of this first round is Macron himself. Until a few days ago, his success had seemed obvious thanks to his leading role in the Ukrainian conflict and in the semester of the French presidency of the EU.

Not anymore.

The distance between Macron and Le Pen is likely to be much smaller this time than in 2017 although, if you look at the results of the first round, Le Pen is (about) just one point further behind Macron than she was back in 2017. But that isn’t much of an advantage for Macron: Le Pen can make it up easily with the Zemmour votes.

Indeed, Zemmour was quick to call on his followers to vote for her, saying “Le Pen faces [Macron], a man who has let 2 million immigrants enter France, and who has not said a word about security, immigration during his campaign and who will do worse if he is elected. That’s why I call on my voters to cast a ballot for Marine Le Pen.”

All the other major contenders – Hidalgo, Jadot, Pécresse – have called on their supporters to vote for Macron. So has Mélanchon – even saying it four times in his speech – but observers don’t believe they will follow through: The expectation is that one third will vote Macron, one third will vote Le Pen and one third will abstain.

So polls, for now, give the outcome of the second round as very close. Ifop pollsters predicted a very tight runoff, with 51 percent for Macron and 49 percent for Le Pen. The gap is so tight that victory either way is within the margin of error.

Other pollsters offered a slightly bigger margin in favor of Macron, with up to 54 percent. But that was in any case much narrower than in 2017 when Macron beat Le Pen with 66.1 percent of the votes.

The second round: A referendum on Macron and Frexit, whether or not France stays in the European Union and leaves NATO

In short, the game is on for the second round. The big open question is absenteeism: Normally up to 80% of the French electorate turns up for presidential elections, this time they were less than 75%. So there is space there for either contender to gather more votes.

Macron, who hadn’t really campaigned so far (he’d held just one campaign event), has announced he will “invent” new proposals to “rally” everyone and is going full blast, starting with a meeting tomorrow in Lens, in the north, a mining area that is behind Le Pen, and following with a series of other towns through the week.

Meanwhile, Le Pen says the second round will be a referendum on the President himself, on how he governed in the past five years. And she’s hoping to rally all the discontented around her agenda. Expect her to double down on her populist promises to cut taxes and promote every possible measure to please the electorate without regard for consequences on the state’s budget, or even whether her proposals are at all feasible.

It will also be a referendum on her, on what she stands for, and especially on her main “national rally” message which, bottom line, is very Trump-like: Make France Great Again (MFGA) – something that can only happen at the expense of the European Union, of the special partnership between Paris and Berlin that had marked the Merkel years and that Macron has revived, and of course of NATO itself.

And that alone is something deeply worrying for the White House: A Le Pen win could unravel the Western alliance and change the course of the war in Ukraine.

The financial markets, unsurprisingly, are looking with agitation at the hypothesis of a vote for Le Pen, and with some reason: Le Pen, with a rallying MFGA message has strengthened since the 2017 elections and knows how to strike the right chords among the undecided, cracking that “republican front” that should oppose the election in the second round.

The political coalition against Le Pen, father and daughter, has held up several times since 2002. But if it collapses, if Macron is unable to convince the electorate that he can “invent” something they all like, then the course of France and Europe we have known so far will change.

And not for the better.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: Macron – Le Pen (creative commons)