The Ukraine war is unlike any other. I’ve said this before but here I would like to explore all the ways in which it’s different and how this is likely to change the world we live in. No other war in recent memory has been waged with so many sanctions on such an unprecedented scale and caused so many people to flee – 4.1 million refugees in just one month, according to the latest estimates and over 6 million internally displaced persons. None has led to so many high-level talks (with no concrete results so far), including a virtual tour of major Parliaments by Zelynsky (with a notable boost to his image).

And, remarkably, none before the war in Ukraine, has exhibited (almost) zero recourse to the United Nations. But with the Bucha atrocities that came to light today as the Russian army retreats, this could change. The discovery of mass graves with over 400 dead has led to an outcry that this is indeed genocide and demands for justice are renewed (while Moscow of course denies the fact). The UN Secretary-General was among the first to ask for an independent investigation.

Thus, it would appear that the UN might finally come on the scene and offer its “services”, at least in the form of recourse to the International Criminal Court with jurisdiction to prosecute individuals for the international crimes of genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and the crime of aggression.

This absence of the UN on the scene of the conflict so far is what makes this situation so different from other wars such as in Syria or Yemen: Here, the UN simply does not appear in any of its traditional roles: (1) assistance for refugees, an issue within the mandate of UNHCR, in this case, it limited itself to gathering cash donations leaving the matter largely in European hands; (2) offering intermediation or providing other peace-securing activities that the UN normally engages in. With the Boucha massacres, this could change, but it still will not provide the UN with a major role right now in the ongoing war: International justice is necessarily slow-moving, investigations take time, and the result will likely be seen a few years from now.

Sure, there have been resolutions condemning Russia at the level of the General Assembly, on March 2 and March 24, and a substantial number of countries voted in favor, 141 the first time, 140 the second time.

Draft resolution A/ES-11/L.2 condemning Russia’s violations of international humanitarian and human rights law in #Ukraine 🇺🇦 overwhelmingly passes in the @UN General Assembly:

140 in favor ✅

5 against❌

38 abstentions pic.twitter.com/VnYT012EHP— UN Geneva (@UNGeneva) March 24, 2022

But, significantly, no resolution passed the UN Security Council, which explains the UN’s absence in this conflict and inability to assist in conflict resolution. As is well known, no military operations of any kind including for peace-keeping can be launched without Security Council approval. Russia, one of the five permanent members with veto power, has ensured the UNSC will remain paralyzed.

The irate Ukraine Ambassador famously told the UNSC president when the resolution failed (on February 25): “Your words have less value than a hole in a New York pretzel’.

The geopolitical implications are many, and depending on how long the war continues, they could result in more or less severe impacts. No doubt, it’s too early to tell how all this will end and what the ultimate outcome will be in terms of geopolitical changes. But one thing is certain, the world will not go back to the multi-polar geopolitical balance it had known before the war in Ukraine.

A first important point to keep in mind: The Ukraine war is as much an economic as a military war, as a result of the mounting sanctions slapped on Russia. Unlike the Syrian or Yemen war, it brings the impact of war to the door of non-participants: Higher energy, food, and industrial metal prices are impacting everyone, advanced countries and the developing world alike.

As economists Nouriel Roubini and Brunello Rosa recently wrote on PS in a remarkable analysis, stagflation is coming, reminding us of the 1970s economic shocks caused by OPEC when it quadrupled the prices of fuel. They argue that while fiscal and monetary authorities “currently have the situation under control”, they are very likely to “run up against the limits of their policy options as conditions change.”

The two economists see two possible endgames: (1) “higher inflation, lower growth, higher long-term interest rates, or softer sanctions” as policymakers are likely to give in to citizen demands for price control over food or fuels; or (2) policymakers may settle for only partly achieving their policies, leading to a “suboptimal macro outcome”. And they conclude: “Either way, households and consumers will feel the pinch, which will have political implications down the road.”

Political implications they don’t spell out in their analysis, but obviously what is meant is much more than just “feeling the pinch”. Outcomes are political instability, tensions, and protests of the kind we currently see developing in Sri Lanka where rising prices and government mismanagements have sent people in the streets. The government there faces a stark conundrum: Feed the people or declare default? What is happening in Sri Lanka today could soon happen around the world in many countries.

But there’s a major geopolitical impact too: The Ukraine war with its cortege of sanctions could potentially throw Russia in the arms of China. And with the impact of sanctions ratcheting up, Russia might be left with no alternative other than to look to China for its main export: gas and oil.

How likely is it? It could happen sooner than we think as shown by the ongoing dispute between Putin and Europeans as he asks for payments for gas in roubles – an obvious way for Putin to try and circumvent the impact of sanctions that have caused a dramatic fall in the rouble. For now, Putin appears to have backed down, but the question obviously is not settled.

We must assume the war is likely to continue long enough for sanctions to achieve their full impact. And the war could last a long time even though the Ukrainian army is much smaller than the Russian army. It could easily turn into a guerilla-style war as civilians are mobilized to fight alongside the army. Ukrainians show the same courage and determination as the Afghans did when they succeeded in fighting off the Soviet army – in both cases with support from the West providing arms.

This is something Putin cannot overlook and he will eventually have to come to terms with the reality on the ground. While he has won on one major point, the neutrality of Ukraine which, as Zelinsky said, will not join NATO. But he has lost on the question of the “integrality” of Ukraine’s territory: He got Crimea in 2014, how much he can get of the Donbas is an open question; whether the southern cities of Mariupol and Odesa continue to resist will be key to determine the final outcome.

Signs of a rising new bipolar world: A stronger EU; strained US-Russian diplomatic relations; Russia courting India

No matter how the war is ultimately settled, we are likely to see a radically different world from the multi-polar one we’ve been living in since the fall of the Wall of Berlin and the collapse of the Soviet Union. For the first time, we could go back to a bipolar world, with China and Russia on one side, and the United States and Europe on the other.

Nowhere is the ongoing geopolitical change more visible, perhaps, than in Germany which has totally re-appraised its military stance, finally devolving 2 percent of its GDP to military expenditures (as per NATO commitment, something it had never done before). And that implies a similar deep reorientation in its foreign policy and energy policies.

Equally visible is the recompacting of the EU: We now regularly see something we’ve never seen before, the head of the EU Commission, Ursula von der Leyen talking one-on-one with US President Biden and China leader Xi-Jinping; and a multiplicity of high-level talks, including the just-held EU-China Summit:

But it’s not just diplomatic talk, it’s also a take-over by the EU Commission of several European Union-wide decisions and policies, notably:

(1) For refugees, the EU has activated an exceptional protection scheme, a directive that allows Ukrainian refugees to remain one year in any European country;

(2) on gas, hydrogen and liquefied gas, the EU Commission will make grouped purchases as it had done for Covid vaccines;

(3) to achieve what it calls “strategic autonomy”, the EU Commission is working on an accelerated energy transition plan that should ensure total European “independence” from Russia by 2027, and that would include a strong push for alternative, “green” energy sources.

US-Russia diplomatic relations are strained just as they used to be during the Cold War: Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has made John Sullivan’s tough job as U.S. envoy to Moscow even harder as he grapples with the Kremlin’s nuclear saber-rattling and threats to sever relations while keeping his embassy running on one-tenth the normal staff.

Russia is not standing still, quickly courting major countries in the developing world that are not aligned with the West, exactly as the Soviet Union used to do: It will increase its use of non-Western currencies for trade with countries such as India, Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov said, as he hailed India as a friend that was not taking a “one-sided view” on the Ukraine war.

But it’s not just India. The countries likely to be courted by Russia can be easily found in the list of 38 countries that abstained from voting on the UN General Assembly resolution condemning Russia. So, yes, Russia is isolated but not quite that alone.

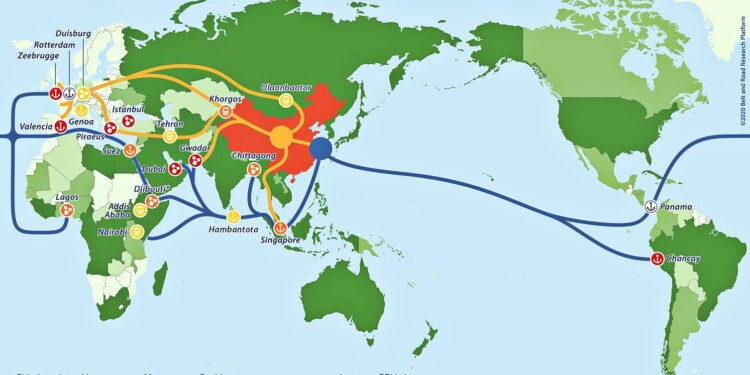

China is not standing still either. For now, it has chosen the commercial road to world power, with its famous Belt and Road Initiative that has entered Europe, not only in Greece, taking over the Piraeus port but in Montenegro, and investments beyond, actually everywhere including Africa (much to Europe’s dismay as it considers Africa its backyard).

But will China stay business-like and peace-loving forever? Nothing is less certain.

Some observers, like professor Slavoj Žižek, who teaches at the University of London and is the author of Heaven in Disorder argued in a recent article on PS arrestingly entitled “From Cold War to Hot Peace” that China could even entertain military operations, for example, the take-over of Taiwan, just like Putin took over Crimea. And he points to reports that Chinese official media have begun to hint more openly that a military “liberation” of Taiwan will be needed, and the Chinese propaganda machine has increasingly urged nationalist patriotism, with frequent accusations that the US is eager to go to war for Taiwan. Last fall, Chinese authorities advised the public to stock up on enough supplies to survive for two months “just in case.” As Žižek notes, “It was a strange warning that many perceived as an announcement of imminent war.”

How viable is this new bipolar world; put another way: how solid would a Russia-China partnership be?

That we’re headed toward a bipolar world is far from certain. Much depends on the solidity of the Russia-China partnership, and historically, these are two countries that have rarely come together, even in Soviet times when they both shared the Communist credo.

How welcoming China will be to its newfound Russian partner is not clear: China probably cannot afford to jeopardize its trade with the West. Commercial ties with Europe and the US are its lifeline. Russia does not offer a convincing alternative, taking in only 2 or 3 percent of China’s exports compared to the EU’s 25%. Indeed, Chinese exports to Russia, small as they are, are slowing as the rouble swings in value, a sign that Western sanctions over Russia’s invasion of Ukraine are impacting China, even as it stands by Russia diplomatically.

Perhaps a Russia-China partnership is not as solid as one might expect as Russia, aside from offering a much smaller market for China compared to the West, could appear to be a hobbled partner in other ways.

Going against Russia is a poor demonstration of its armed forces that failed to take Ukraine in the planned 2-day blitzkrieg, got its 40-mile convoy stuck, couldn’t take Kyiv, and is now suffering counterattacks from Ukraine.

Also, Russia is weakened by the war in another way: It is suffering from a tech brain drain, with up to 70,000 computer specialists having already fled and another 100,000 who might soon leave the country – and they’re not going to China (they’re mostly going to Europe).

In short, the game is not done yet. Stay tuned for further unexpected twists and turns, because one thing is certain, we are on the brink of major changes.

Of all the international players, the one that needs to change the most is the United Nations Security Council

The Ukraine war has proven beyond doubt that the UN is not “fit-for-purpose” when it comes to its most fundamental role: Preventing war.

The UN was created coming out of World War II to avoid all future wars, and it has proved to be unable to do so – incapacitated by the way the UN Security Council is set up, with five countries holding a permanent seat with veto power: the US, France, UK, China and Russia.

Recently, the Ukrainian ambassador at the UN has forcefully argued that Russia should be removed from the Security Council and that it had no right to its seat.

This was echoed by one of America’s foremost experts on Russia, Michael McFaul who tweeted asking why Russia had inherited the Soviet Union’s permanent seat on the Security Council:

International law experts, I know that Russia inherited “de facto” the USSR’s seat on the UN Security Council. Was that ever ratified in a formal vote? Was it legal? Maybe time to give that seat to another Soviet successor state, Ukraine?

— Michael McFaul (@McFaul) March 6, 2022

The question is complex, and Russia appears to have “de facto” inherited the Soviet Union’s seat without going through the normal procedure of voting, as was done for other countries. The successor states of the former Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia had to reapply to join the U.N. individually. Neither the Security Council nor General Assembly ever voted to approve Russia’s membership.

Is it impossible to remove Russia from the Security Council? No, China provides the example of how this can be technically done; a long process to be sure, drawn out from 1945 to 1971, but it eventually achieved its purpose: China got into the Security Council and Taiwan was out.

Ukraine would need to rally the General Assembly members to pass a vote – it needs two-thirds of them – to either declare that Russia can’t possess the Soviet Union’s seat and needs to reapply or pass the seat — and its veto power — on to another of the Soviet Union’s successors. But even if it managed to obtain this from the General Assembly, China, since it has veto power in the UN Security Council, could still veto any set of international sanctions on Russia.

We’re back to square one – and the urgent need to reform the UN Security Council and remove the veto power once and for all. Or human history will go on as it has up to now, subject to the whims of the powerful and wars that nobody can stop.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: Map showing the importance of China’s Belt and Road Initiative and related trade: China trades with all the countries in green on the map and is the #1 trade partner in those that are dark green Source: screenshot from Belt & Road Research platform