Individual household choices about food, clothing, transportation, and housing account for half of all global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and nearly all biodiversity loss, with G20 citizens contributing disproportionately. Even after reducing these emissions, many communities will still face challenging adaptation and restoration problems requiring climate action on both an individual and collective scale.

To make matters worse, beyond environmental issues are other crises requiring behavior change of equally historic proportions, including an ongoing global pandemic. Unfortunately, the changes needed to deal with these problems effectively have been slow: only about 8% of the US population takes regular climate action, and vaccination rates continue to fall short of the levels required for herd immunity.

All in all, policymakers have their work cut out for them.

The problems we face are so enormous that we need virtually everyone to take every action within their means that they possibly can. A whole-of-society approach to accomplishing this, however, can fail to account for the different motivations of individuals and groups. Because some interventions are more effective for certain groups, we must consider the unique characteristics of the segments within the population to solve the difficult problems facing humanity.

The Social Diffusion Model, a way of analyzing how behavior spreads

We recently proposed a new Social Diffusion Model of climate action that does precisely this. This model is built upon foundational theories of human behavior from psychology and sociology, and the diffusion of innovation theory from communication science.

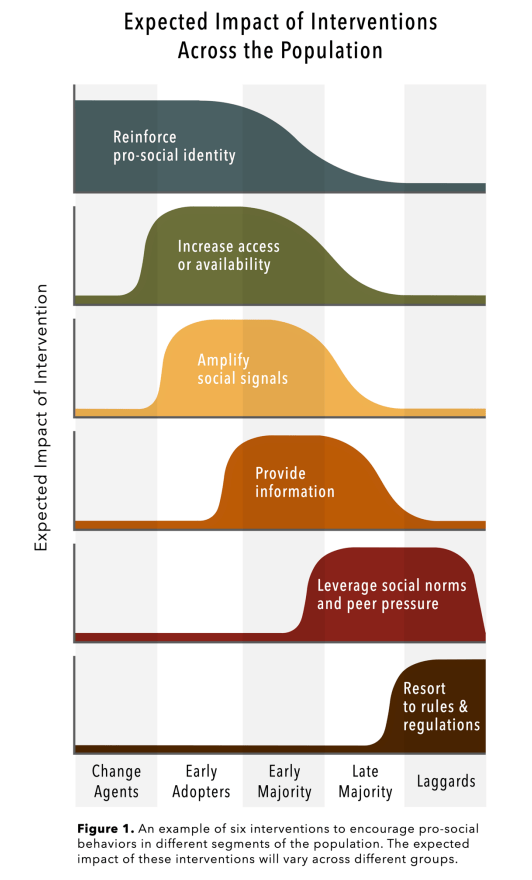

The model describes the driving and restraining forces of five population segments (Change Agents, Early Adopters, Early Majority, Late Majority, and Laggards) and suggests interventions tailored to these forces to increase a given pro-social behavior in each segment. To promote climate action, either driving forces need to be strengthened or restraining forces should be reduced.

The graphic below presents the expected impact of behavioral interventions across different segments as illustrated by this model.

Consider the example of promoting a plant-based diet, a critical behavioral shift for planetary and human health. Although more people than ever are switching to meat alternatives, commercially available meat substitutes are still relatively new. To diffuse the adoption of a plant-based diet, it is crucial to consider the different motivational forces for each segment.

Change Agents

Individuals driving the innovation, the Change Agents, are motivated by their pro-environmental identity and the potential payoff of being first to market. Meanwhile, Change Agents need to overcome resource constraints, policy and infrastructure gaps, and the risk of low interest in their new plant-based products.

Early Adopters and Early Majority

Early Adopters, like Change Agents, are driven by pro-social motivations and a desire to be the first among their peers to try plant-based products. Their restraining forces, however, center more on feasibility. An example would be the low availability of meat alternatives and the lack of information about their health and environmental benefits. The Early Majority emulate the actions of Early Adopters but still face similar restraining forces such as low availability.

Late Majority and Laggards

For the remaining 50% of the population, the Late Majority and Laggards, their restraining forces arise from skepticism and strong ideologies and values. Therefore, interventions should focus on communicating immediate personal benefits, conveying high-quality information via trusted messengers, engaging with appropriate social networks and peers from these groups, and using mandates and regulations.

The Social Diffusion Model and Vaccine Hesitancy

The Social Diffusion Model is not limited to pro-environmental behaviors. Immunization against SARS-CoV-2, for example, is another pro-social behavior currently spreading through the population. Although most people in higher-income countries are now vaccinated, many of those countries still struggle to reach the substantial majority vaccination rate required to prevent future outbreaks.

In this case, the restraining forces affecting the Late Majority and Laggards could involve skepticism about the safety of vaccines or the threat of COVID-19. Individuals in these groups tend to adopt a “wait-and-see” approach to the vaccine, only taking it when the driving forces overcome the significant restraining forces.

At this point in the social diffusion process, existing social pressure, an essential driver for these groups, may be overwhelmed by an abundance of information and choices. Interventions to further increase uptake of vaccines should therefore increase social pressure by relying on social norm messaging, amplifying peer pressure or influence, and having trusted in-group role models present pro-vaccine information.

Tailoring interventions for greatest impact

The above examples represent just two of many behaviors necessary to solve the multiple crises facing humanity. In the case of choosing plant-based proteins over meat, diffusion in higher-income countries is currently limited by the restraining forces affecting Early Adopters and the Early Majority, as the diffusion has not reached the Late Majority or Laggards. For vaccination against COVID-19, diffusion has progressed past these stages in most higher-income countries.

Interventions by governments, non-profits, and social enterprises intending to encourage these behaviors must consider the optimal interventions for each segment in the population. Tailoring interventions to the differing views, values, and informational needs of the segments they hope to target could be the difference between successful behavioral change and continued behavioral stagnation.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: Extinction Rebellion rally in 2018. Featured Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons